Beijing Should Scrap the GDP Target; Obsession with GDP Growth Pushes the Bureaucracy to Borrow and Spend, Often Recklessly

January 12, 2014 Leave a comment

Beijing Should Scrap the GDP Target

Obsession with GDP Growth Pushes the Bureaucracy to Borrow and Spend, Often Recklessly

ANDREW BROWNE

Jan. 7, 2014 8:31 a.m. ET

China is the only major economy left in the world that sets hard growth targets. The WSJ’s Andrew Browne tells Abheek Bhattacharya why it should stop. BEIJING—An alarming surge in local government debt reflects China’s obsession with gross domestic product growth, which encourages officials at every layer of the bureaucracy to borrow and spend, often recklessly.“GDP worship,” as the official Xinhua news agency has described it, is a prime reason why local debt ballooned to $2.9 trillion by the end of June 2013, the equivalent of 33% of GDP, up from just $1.7 trillion at the end of 2011, according to a government audit.

Left unchecked, this buildup could threaten China’s financial stability, which is why the Communist Party last month announced a new incentive program to reward local officials more for the quality of growth, including attention to the environment, rather than the quantity.

Here’s another idea: Scrap the national GDP target altogether. It would send a powerful message that Beijing is serious about shifting the drivers of growth.

China is the only major economy in the world that sets hard growth targets. The number has been set at 7.5% for the past two years. Other countries, including the U.S., have agencies that merely forecast growth.

The target is a relic of the Stalinist planned economy, the basis on which the government planned the allocation of scarce resources for industrial production. Its continued existence is testament to how far China has to go to fully embrace a market economy, one that operates according to market signals.

Career success for officials was explicitly linked to the speed of growth, resulting in mountains of debt as local governments borrowed to invest in everything from hotels to highways and subway systems.

A side effect of the go-for-growth mentality: environmental devastation that’s turned into a public health crisis and a political challenge for the government.

As a result, some economists see scrapping the target as an obvious step. Eswar Prasad, a former senior China official with the International Monetary Fund and now a professor at Cornell University, says the target “has become an anachronism.”

Dropping it, he says, “would serve as a clarion call that the government’s priorities have shifted away from growth at all costs toward a greater emphasis on a growth model that is balanced and sustainable.”

But, despite a Communist Party meeting last year that promised a “decisive” role for markets as part of an economic overhaul package, there’s little public discussion in China about jettisoning this socialist holdover.

That, say economists, highlights an issue that must be addressed if China wants to get a grip on out-of-control local debt: The top leadership itself is conflicted about the pace of growth and its importance in planning and official life.

In public, senior leaders have signaled that they are comfortable with a slowing after three decades of double-digit expansion, and that their focus has now shifted to implementing reforms.

Yet their recent actions have made clear they still believe that meeting the target is critical.

When growth softened earlier last year, some economists thought that Beijing would stand back and let gravity take over. Instead, central authorities apparently took fright and started pumping credit again—undermining their own message to local levels that growth isn’t everything.

“They care quite a bit about growth—more than we thought just a few months ago,” says Louis Kuijs, the chief China economist for the Royal Bank of Scotland.

But now would be a good time to abandon GDP targets because the global economy is picking up, says Rodney Jones, a Beijing-based principal of Wigram Capital Advisors. He argues that insisting on a certain level of growth every year, regardless of the global environment, distorts the Chinese economy. “There is a business cycle. Growth ebbs and flows,” he says.

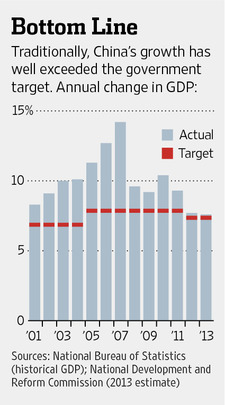

Traditionally, the target was thought of as a “bottom line” rather than an ambitious goal to stretch toward. Comfortably exceeding it, therefore, became a marker of the government’s credibility.

That has imbued the number with a political significance, complicating any decision to dump it.

Just how sensitive the target remains to the Communist Party was demonstrated last year, when finance minister Lou Jiwei dropped to a group of reporters in Washington that a growth rate of 7%, or even 6.5%, wouldn’t be a “big problem.” State media quickly corrected him, insisting there was no change in the 7.5% target.

The target is politically important in other ways, too. It reflects the government’s priority to grow the economy fast enough to provide full employment—and social stability.

Plus, the targets feed into the mathematics behind a national goal to double GDP, as well as annual per capita income, between 2010 and 2020.

Yet China’s demographics are changing rapidly: The number of workers has peaked and is now falling, meaning that China can achieve its employment goals with slower growth. And China can afford to shift down a gear, to around 7% growth, and still meet its 2020 goal.

Besides, the government must weigh the political risks associated with slowing GDP against the very real danger of a financial blow-up.

Premier Li Keqiang is scheduled to announce the 2014 growth target at the National People’s Congress in March. Recently, he indicated that 7.2% growth would be sufficient to ensure employment, setting off speculation that he might be getting ready to unveil a lower target, possibly of 7%.

That would be a bold step—but not nearly as bold as discarding the target completely.