Brazil’s Class Struggle Goes to the Mall

January 19, 2014 Leave a comment

Brazil’s Class Struggle Goes to the Mall

LORETTA CHAO and ROGERIO JELMAYER

Jan. 17, 2014 7:59 p.m. ET

Protests broke out at the Campo Limpo mall in São Paulo on Thursday against an injunction to forbid rolezinhos, big gatherings in shopping malls. Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

SÃO PAULO—For as long as many can remember, a rolezinho was slang for a gathering of teenagers in a public place. The teens organize a group and arrange a meeting place, perhaps outdoors, in a park. In São Paulo, it is often at a shopping mall, a favorite weekend hangout across all social classes.But in recent weeks, rolezinhos growing to as many as 6,000 participants via social-media sites have brought to the forefront Brazil’s deep divide between rich and poor. On Jan. 11 in Itaquera, a massive mall in São Paulo’s up-and-coming east zone, hordes of rowdy teens flooded the halls prompting calls to the police, who shot at the adolescents with rubber bullets and tear gas. More gatherings are being planned around Brazil this weekend, including in Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia.

São Paulo police say they are investigating some of the teens for criminal conspiracy and disturbing the peace, prompting criticism that the teens are being persecuted because they are from Brazil’s lower classes. Those critics note that few robberies took place despite the commotion—only one store in Itaquera reported catching someone leaving with a hat and a pair of shorts that weren’t paid for during a Dec. 7 mob of 6,000 teens, according to mall administrators.

But others, including famous TV anchor Rachel Sheherazade, are publicly calling for punishment of the teens, describing them as criminals and troublemakers, and condemning their disturbances in shopping malls, which are technically private property. “Shopping malls became popular havens in Brazil because they were an alternative…for people seeking security,” Ms. Sheherazade said on her show on SBT, Brazil’s third-largest network by audience. “But now that haven has been violated.”

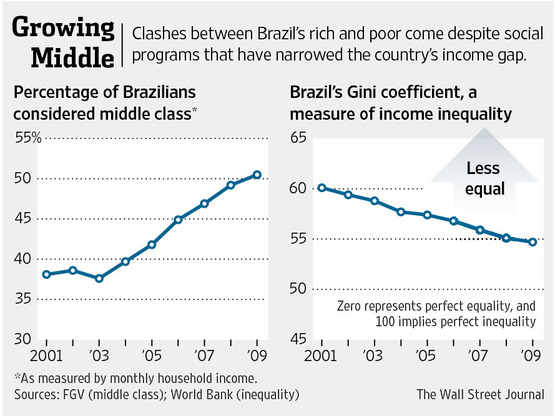

Brazil’s income disparities are widely acknowledged but rarely manifest themselves in such high-profile clashes. The nation’s wealth gap has actually narrowed over the past decade as the federal government created social-welfare programs bringing millions of poor Brazilians into the middle class—but researchers say ideologically, the classes are more at odds than ever.

“This debate highlights some of the social apartheid in Brazil,” said Rafael Alcadipani, a social-science researcher at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo. “There is in Brazil a new resurgence of people who are very conservative…the rich, upper-middle class and middle class who think they have been left behind by the government.”

A national survey of 3,500 people conducted by Data Popular, a firm that specializes in research of Brazil’s new middle class, found that half of Brazil’s elite classes prefer “environments with people on my social level.” More than a quarter said subway systems have increased the “circulation of undesirable persons” in their region. “The debates provoked by rolezinhos lay bare existing prejudice,” said Data Popular CEO Renato Meirelles.

The rolezinhos are flaring up at a sensitive time in Brazil. Last summer when young people protested against rising bus fares, a violent reaction by police in São Paulo prompted hundreds of thousands of people around the country to join a weekslong movement that paralyzed Brazil’s major cities and shook the country’s political establishment.

If police continue to react violently to the teens as they did with protesters last year, analysts say riots could flare up again. Some special-interest groups have tried to use the media attention to turn rolezinhos into protests, including a group advocating rights for homeless workers that joined a rolezinho in São Paulo’s south zone on Thursday.

Authorities have already softened their tone. São Paulo state Gov. Geraldo Alckmin said “The rolezinhos are a good thing, this is a cultural and fun activity of our young people….What is a police matter is if [they] turn to violent activity with confusion, robberies.”

The organizers and many of the participants say the rolezinhos aren’t meant to be political. In fact, the teens who organized them on Facebook regularly post little more than “selfie” photos shot with their smartphones and links to their favorite songs. One rolezinho organizer who goes by the name Giselle Tais on Facebook posted a message on Wednesday on her wall saying she just wanted to “go out to the mall and have some fun.”

“Stop being hypocrites and let us have our own space,” she wrote.

Robson Justino da Silva, a 15-year-old from São Paulo’s south zone, said “it’s cool going to these rolezinhos, first of all because you don’t have to pay like you do for a party, and there’s lots of girls, too. But malls aren’t very good for making out.” Mr. da Silva, a student who was one of the thousands chased out of Itaquera mall by police over the past two months, said his parents prefer he goes to the mall than hang out in the streets because “there’s more security there.”

But the actions of these poor teens, who come from groups often dismissed by much of Brazilian society as waiters or people working in the malls, are now becoming a statement against what they see as class- and race-based prejudice, said Mr. Alcadipani, who has spoken with some of the teens who were detained by police following a gathering. They are saying, “We want to be part of the party,” he said.