China Trust “Bailout” To “Unidentified Buyer” Distorts Market As “Risks Are Snowballing”

January 29, 2014 Leave a comment

China Trust “Bailout” To “Unidentified Buyer” Distorts Market As “Risks Are Snowballing”

Tyler Durden on 01/27/2014 10:35 -0500

In a 2-line statement, offering very few details, ICBC’s China Credit Trust Co. said it reached an agreement to restructure the CEG#1 that ha sbeen at the heart of the default concerns in recent weeks. The agreement includes a potential investment in the 3 billion-yuan ($496 million) product but didn’t identify the source of funds, or confirm whether investors would get all of their money back. The media is very excited about this entirely provisional statement and we note, as Bloomberg reports, investors in the trust product must authorize China Credit Trust to handle the transaction if they want to recoup their principal which will involve the sale of investors’ rights in the trust at face value (though no mention of accrued interest). As BofAML notes, however, “the underlying problem is a corporate sector insolvency issue… there may be many more products threatening to default over time,” and while this ‘scare’ may have raised investors’ angst, S&P warns “a bailout of the trust product [leaves] Chinese authorities with a growing problem of moral hazard,” and they have missed an opportunity for “instilling market discipline.”

1) ICBC issues a 2 line statement on a CEG#1 restructuring – no details and no comments from anyone involved

China Credit Trust Co. said it reached an agreement to restructure a high-yield product that sparked concern over the health of the nation’s $1.67 trillion trust industry…

Beijing-based China Credit Trust’s two-line statement on its website didn’t identify the source of funds, or say whether investors would get all of their money back.

2) Investors claim they “could” be able to sell their rights to the CEG#1 trust to an “unidentified buyer” at par (though receive no accrued interest as far as is clear)

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd. told investors of a China Credit Trust product facing possible default about an offer in which they can receive back their full principal, according to an investor with direct knowledge of the offer.

Rights in the 3 billion-yuan ($496 million) product issued by China Credit Trust Co. can be sold to unidentified buyers at a price equal to the value of the principal invested, according to one investor who cited an offer presented by ICBC and asked to be identified only by his surname Chen.

China Credit Trust earlier said it reached an agreement for a potential investment and asked clients of ICBC, China’s biggest bank, to contact their financial advisers.

3) “A default was bound to lead to systemic risks that China is unable to cope with, so in that sense a bailout is a positive step to stabilize the market,”

As one analyst noted, the PBOC is running scared…

“It indicates the government still won’t tolerate any ultimate default and retail investors will continue to be compensated in similar cases.”

4) This confirms S&P’s recent warning that “A bailout of the trust product would leave Chinese authorities with a growing problem of moral hazard,” and an opportunity for “instilling market discipline” will have been missed.

…said Xu Gao, the Beijing-based chief economist at Everbright Securities Co. Still, implicit guarantees distort the market and “delaying the first default means risks are snowballing,” he said.

5) of course, China may have shown its moral hazard hand on this occasion but as BofAML warns, “We suspect that, at a certain point, the involved parties will be either unwilling or unable to bail them out [again], which may trigger a credit crunch…The underlying problem is a corporate sector insolvency issue… there may be many more products threatening to default over time.”

There are plenty more trust products facing maturity/default in the short-term…

The most volatile part of the system is the financial market and the weakest link of the financial market is shadow banking. Within the shadow banking sector, we believe that the trust market faces the biggest default risk because credit quality here is among the lowest. The stability of the shadow banking sector is based on public confidence and any meaningful default will chip away some of the confidence. We suspect that trust defaults by private borrowers may work on public sentiment gradually while any LGFV trust default may immediately trigger significant market volatility. 2Q & 3Q this year will be another peak trust maturing period.

China’s Default That Wasn’t

AARON BACK

Jan. 27, 2014 9:26 a.m. ET

Those who hoped a high-profile default would deliver a needed shock of moral hazard into China’s financial system will be disappointed. The question is whether investors are getting the message anyway.

Like clockwork, a mysterious third party has sprung to the rescue, allowing China Credit Trust to repay the principle on high-yield investment products tied to a struggling coal miner. Savers will miss some interest payments and get a lower effective yield, but otherwise escape unharmed. So does the reputation of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, 601398.SH -1.18% the country’s largest commercial lender, which sold the trust products to clients.

In a $9.4 trillion economy, a nearly $500 million set of trust products appears too big to fail.

The hand of the state seems to be at work. Officials in the miner’s home province were actively involved in coming up with a solution, The Wall Street Journal reported. The bailout involves the third-party investor taking an equity stake in the coal company, which came only after the company suddenly gained approval to restart a closed mine.

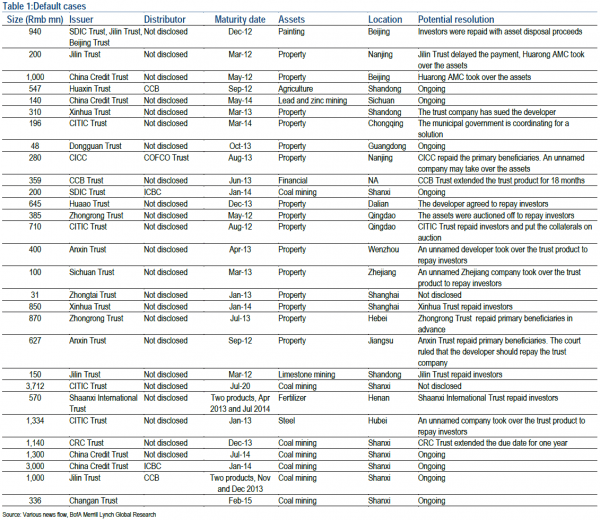

In China, this kind of result is typical. More than 20 trust products valued at a total of more than $3.9 billion have run into payment issues since 2012, according to UBS economist Wang Tao. In around half of these cases, investors were paid back by trusts or third-party guarantors, while others have been caught up in lengthy legal processes.

There are signs that the publicity around the case may help educate investors on risks in the system. ICBC Chairman Jiang Jianqing said on CNBC he hoped such a learning process was taking place. So should ICBC shareholders. If pressured by customers or the government to take such products onto its balance sheet, the bank would see a substantial erosion of capital ratios.

According to Nomura economist Zhiwei Zhang, sales of trust products in January are down nearly 70% from December and 50% from a year earlier as investors shrink from risk. This will intensify credit stress, making it harder for trusts to roll over short-term loans to stressed borrowers. Expect more such episodes.

This is all part of the difficult process to allow genuine failures in the Chinese financial system, ostensibly what the Communist Party leadership meant when it said markets should play a “decisive role” in the economy. For the past several months, new awareness of risk has showed up in financial prices, with yields on interbank loans and government bonds rising and becoming more volatile.

Like many times before, an unknown hero rode to the rescue in this credit drama. But at least some Chinese investors may be slowly waking up to the fact that there aren’t enough white knights to save everyone.

Shadow Lender Strives to Avert Loss

China Credit Trust Co. Appears to Have Found a Way to Pay Back Investors

LINGLING WEI

Updated Jan. 27, 2014 4:04 a.m. ET

BEIJING—China avoided a potentially destabilizing hit to its creaky financial system after a major shadow lender arranged a bailout for buyers of an investment product that was on the verge of going bust.

Analysts said the fact that investors will avoid a financial hit—and that it remains unclear who will pay the tab—risks sending a message that reckless investing and lending can continue with impunity, analysts said. That, they said, could ultimately damage the financial system.

China Credit Trust Co. told investors on Monday that it will restructure the loan behind a 3 billion yuan ($496 million) high-yielding investment product that is scheduled to come due on Jan. 31. Under the restructuring, the roughly 700 investors in the product would get their principal back but not the last of three interest payments, according to two investors who have been notified of the payment plan.

China Credit said it made the move by swapping the debt for equity in the borrower, a struggling coal-mining company. The equity was then purchased by an investor it didn’t name. China Credit officials confirmed the payment plan, as well as its notice to investors, but declined to comment further.

The move could help calm near-term market jitters over what are known as trust products, a pillar of China’s non-bank shadow-banking system. Had China Credit missed the Jan. 31 payment, the trust product would have become the first to result in significant losses for investors and could have shaken confidence in China’s financial system.

But the restructuring leaves unanswered long-term questions about China’s financial health, analysts say. “The underlying issue is that there is too much debt in the system that has gone to wasteful projects,” says David Cui, China strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

“At a certain point, the involved parties will be either unwilling or unable to bail out [troubled investors or borrowers], which may trigger a credit crunch,” Mr. Cui says.

Lending by shadow bankers—an assortment of trust companies, insurers, leasing firms and other informal lenders—rose 43% last year from 2012, to 5.165 trillion yuan, data from China’s central bank show, becoming a major factor in China’s rising debt levels.

The shadow banks raise funds by offering yields far higher than are available from ordinary bank deposits, lending to borrowers considered too risky for traditional banks, such as heavily indebted local governments, property developers, coal producers and other companies in sectors burdened by overcapacity.

Some traditional banks in China sell investment products on behalf of these informal lenders as a way to offer higher yields to customers. China’s largest bank by assets,Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. 601398.SH -1.18% , sold the China Credit Trust product to investors but has said repeatedly it isn’t responsible for the risk.

Economists and analysts worry that China’s shadow bankers are introducing risks into its financial system by backing projects that may never pay off and failing to disclose fully what they are asking investors to fund. They say that because banks sometimes sell problem loans to such lenders, but then have to provide credit to the purchasers, the shadow system appears to give banks a way to get rid of problem loans, but doesn’t really do so.

“Chinese banks have already accumulated high credit risks on their balance sheets. But distorted growth in shadow banking could lead to further unintended buildup of credit risks that banks may not fully appreciate,” says Liao Qiang, an analyst at Standard & Poor’s. “Certain parts of the shadow-banking sector, notably trust companies, may prove to be the weak link of China’s financial system.”

China’s economic slowdown could expose more such problems. Government data show that the pace of factory production slowed in December and a purchasing managers’ index indicated that the manufacturing sector had begun to contract in January. China’s economy expanded by 7.7% in 2013, faster than other major economies but well below the double-digit gains of the past 30 years.

Government officials worry that a hit to investors will lead to highly publicized protests and could undermine faith in the overall financial system. In the case of the product sold by China Credit, local government officials have played an active role in putting together the restructuring plan, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter.

China Credit, which is about 33% owned by state-controlled People’s Insurance Company (Group) of China Ltd., sold the product, called “Credit Equals Gold No. 1”, in 2011 through ICBC. It offers annualized returns of between 9% and 11%.

The trust firm then lent the funds to an obscure coal-mine operator in northern China’s Shanxi province, called Zhenfu Energy Group. The company is owned by Wang Pingyan, a farmer turned entrepreneur. As coal prices plunged and some of his mines were forced to shut down due to accidents and local protests, Mr. Wang found himself short of cash to pay off creditors. Mr. Wang, who has been detained by authorities in connection with his financing activities, couldn’t be reached for comment. A representative for his company declined to comment.

China Credit warned investors earlier this month that it might not be able to repay them when the product matures at the end of the month. Last week, China Credit disclosed that the coal company had received key government permission to reopen a mine and that another coal project has won support from local authorities and the community, according to a document reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. Obtaining licenses will permit the mines to start operating and generate revenues.