SATURDAY, JANUARY 25, 2014

Shaking Things Up

By LAUREN R. RUBLIN | MORE ARTICLES BY AUTHOR

Our Roundtable experts Abby Joseph Cohen, Marc Faber, Meryl Witmer and Bill Gross see big opportunities and challenges in 2014.

Sometimes, you need to study the forest, and sometimes you need to examine the trees. This year, with the Federal Reserve turning over a new leaf and ending its bond-buying program, the most successful investors will give equal attention to both.

Barron’s 2014 Roundtable — Part 1

That’s the word — thousands, actually — from the members of the Barron’sRoundtable, who expect macroeconomic forces and policy moves to exert the primary influence on security selection and performance in 2014. Our 10 Wall Street savants made that abundantly clear when the Roundtable convened on Jan. 13 in Manhattan, and the markets, now plummeting amid worries about emerging-market growth and diminished monetary stimulus, are proving them nothing but prescient.

Big-picture issues, from the Fed’s squeeze on its quantitative easing to a jarring slowdown in China, got a full airing in last week’s first of three Roundtable installments. But they remain ever-present — and ever up for discussion and debate — in the current issue, which features the latest investment picks of Abby Joseph Cohen, Marc Faber, Meryl Witmer, and Bill Gross.

Table: 2013 Roundtable Report Card

Abby, a go-to interpreter of economics and markets with a perch at Goldman Sachs, is looking for companies recommended by Goldman’s research department that are likely to benefit from stronger growth in the U.S. Marc, a born investment skeptic who runs his own show out of Hong Kong, can’t find a scintilla of growth on these shores (see what we mean about debate?), but he sees opportunities aplenty to prosper from a coming boom in Asia.

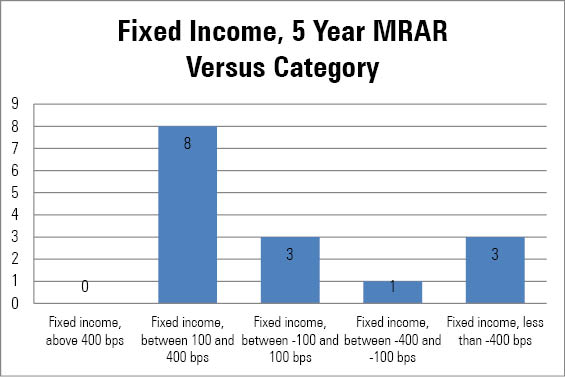

Meryl, Eagle Capital’s resident money-managing math whiz, dissects the prospects for four promising companies that she thinks have fallen unfairly out of favor. And Bill, chief of everything at bond behemoth Pimco, not only shares his insights into the workings of the Fed, but also offers suggestions on how to make money in fixed income, despite the central bank’s fixation on near-zero yields.

Table: 2013 Midyear Roundtable Report Card

Barron’s: Abby, which stocks intrigue you this year?

Cohen: First, I’d like to revisit the bigger picture. We gather here every January as if something special happens on Dec. 31. But in the middle of 2013, there were inflection points that brought changes that could be here for a while. One of the most important was the shift away from liquidity-driven markets to markets driven much more by economic and corporate-revenue growth, and equity-market valuation. The best-performing stocks previously had been those of companies with strong balance sheets that could raise dividends and repurchase shares. Now performance is shifting, at least in the U.S., toward companies with good operating leverage and strong returns on equity that are exposed to economic growth. Viewed another way, value stocks outperformed in the U.S. until July 2013. Now the rally is more growth stock oriented.

Many have said today that the U.S. stock market is the most expensive in the world. Let’s put that into context. The price/earnings ratio of the Standard & Poor’s 500 was 15.9 at the end of 2013, based on estimated 2014 earnings. Europe’s P/E was 13.6, and Japan’s Topix index sold for 14.6. But the economic prospects for the U.S. look far better. Take return on equity, which was 14.2% for the S&P last year, 8.4% for Europe, and 5.3% for the Topix. When we discuss valuations, it is important to focus not only on P/Es. To recap my comments this morning, if you assume no expansion in the price/earnings multiple, the Goldman Sachs research forecast for the S&P 500 is 1900 in 2014. If, with inflation under control, the P/E expands to 18 times earnings, the S&P could rise to 2088.

Abby Joseph Cohen’s Picks

| Investment/Ticker |

1/10/14 Price |

| iSharesMSCIMexico |

|

| Capped ETF/EWW |

$67.08 |

| HollyFrontier/HFC |

49.79 |

| International Paper/IP |

48.93 |

| WyndhamWorldwide/WYN |

72.97 |

| Nordstrom/JWN |

61.11 |

| Extra Space Storage/EXR |

43.57 |

Source: Bloomberg

We’re here to make predictions, so which will it be?

Cohen: The surprises are likely to be to the upside in the U.S. No. 1, we can still make government policy errors, but we’ve already made such big ones. The next issue in Washington will be raising the federal debt ceiling. The market has been through this before, and investors might not react as dramatically as they did in the past. More important, the U.S. economy seems to have more and better traction than it did at the end of 2012. Labor markets are better. Labor productivity has risen by about 2.5% in the past four quarters, which usually is a precursor to job creation and income growth. Also, while there have been significant inflows into the U.S. equity market, a lot of cash is still sitting on the sidelines here and around the world.

When you expect economic improvement, you look for higher-beta securities within sectors [stocks that are more volatile and thus more likely to outperform]. For example, you look at consumer-discretionary, energy, and materials shares. This brings me to Mexico, which will benefit from the improvement in the U.S. Last year wasn’t a good one for Mexico, but there now are signs, particularly in manufacturing, that things are looking up. Government reforms could help the energy sector. Short-term interest rates are 4.5% to 5%, but close to zero in inflation-adjusted terms. Fiscal policy is becoming more expansionary. The Goldman Sachs forecast for Mexican GDP growth in 2014 is 3.3%. We don’t see much change in the dollar/peso exchange rate. One way to gain exposure is through the iShares MSCI Mexico Capped exchange-traded fund, or EWW.

Zulauf: Mexico is structurally sound, but everybody and his brother is invested. If I am right and we see rising risk aversion, the peso will come under pressure. That’s why I would bet against you on this.

Cohen: Turning back to the U.S., economic growth has been held back by fiscal drag [the negative effect of tax hikes], which was considerable in 2013, but will be less so this year. An improvement could add one percentage point to economic growth. In addition, housing has added 0.5 of a percentage point, when the effects of renovation and furnishing are included.

Zulauf: Regarding fiscal drag and the deficit, where did the U.S. government book all the fines it took in from Wall Street? Maybe fiscal drag looked worse last year than it really was.

Cohen: To repeat, the Goldman Sachs economics team thinks U.S. gross domestic product could grow by 3.3% this year. My first stock is in the energy area. Many commodity prices have fallen as a consequence of lower demand from China, changes in India, and the rise of fracking [hydraulic fracturing] in the U.S. The energy sector is now much cheaper than the S&P 500. It sells for 13.4 times estimated earnings and two times book value, compared with 2.7 times book for the S&P. The U.S. has done a phenomenal job in recent years of investing in energy, and it is good to have exposure to a sector that has benefited from research and development and long-term investment. The three countries with the greatest energy resources are the U.S., Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Annual capital expenditures on energy in the U.S. are 14 times greater than in Russia, and 28 times greater than in Saudi Arabia.

Gabelli: It isn’t only the money. It is the technology of horizontal drilling and fracking, which the U.S. developed and no one else in the world understood. Now, they want to embrace it.

Cohen: That isn’t possible in all countries. China, for example, has significant shale-oil resources, but it lacks water. One thing that encouraged me about the Third Plenum [a recent gathering of the Communist Party leadership] is that China acknowledged publicly some of the climate and environmental issues it is facing. It’s not just the dirty air; it’s the dirty water. In the northern provinces, most of the water isn’t suitable for agriculture or drinking, and 50% is too dirty for industrial use.

Zulauf: One of China’s major long-term weaknesses is the lack of good water, and enough water. The water table is much too low, because they didn’t care enough about water during the early stages of the industrial boom.

Cohen: My energy-sector pick isHollyFrontier [HFC], an oil refiner. It closed Friday [Jan. 10] at $49.79. Holly is a U.S. company that benefits from its geography. It has 100% of its refining capacity in the middle of the U.S., and has substantial exposure to light crude. Our energy team expects there will be good spreads [price differences in crude oil] around the world that will benefit U.S. producers. The spread between Brent and West Texas Intermediate crude is going to be lumpy, depending on the refinery, supply, and distribution infrastructure, but we expect it will average about $10 a barrel in the next few years. This means refiners can buy lower-priced crude, but sell gasoline at higher prices.

Holly, like many energy-industry stocks, underperformed the S&P 500 last year. Based on our 2014 earnings estimate, it has a P/E of 9.3. It yields 6.4%. Goldman analysts think the company could earn $5.35 a share this year. Wall Street’s consensus estimate is $4.40. The market capitalization is $9.9 billion.

What is Goldman’s oil forecast for 2014?

Cohen: We’re not big bulls. Our analysts forecast $90 a barrel for West Texas Intermediate at year end, and $100 for Brent.

My next stock is a materials company — International Paper [IP]. In many ways, it dominates the industry. It is No. 1 in container board, No. 1 in corrugated packaging, and so on. Typically, demand for its products goes up when GDP and industrial production rise. Industrial production could exceed 3% in 2014. A lot of people are nervous about paper stocks, given the move toward digitalization. Nevertheless, there seems to be good demand for packaging materials, particularly boxes.

Amazon.com [AMZN] boxes!

Cohen: You got it. A lot of prepared foods also come in boxes now. We know there will be increased supply in the industry, but demand will keep up. International Paper has a history of returning capital to shareholders. It yields 2.6% and could raise the dividend early in the year. The stock closed Friday at $48.93. We expect profit to grow quickly, to $4.40 this year from $3.20 in 2013. Our estimate is above the consensus. The P/E is 11 times our 2014 estimate.

Next, with an improving labor market and a modest increase in household income, we are seeing more spending. In 2013, much of it went to satisfy pent-up demand in housing and autos. This year, there will be more spending in other categories. One of our analysts likes to say that in 2014, people will spend on fun, not food. Wyndham Worldwide[WYN] could be a beneficiary. Wyndham operates several hotel chains, including the Wyndham hotels, Ramada, Days Inn, and Super 8. We are expecting earnings of $4.60 a share in 2014, up from an estimated $3.85 last year. We are notably above the consensus for 2014, which is $4.32. The stock is trading at a market P/E of 15.9 times earnings. [Goldman subsequently lowered its 2013 estimate to $3.82 a share, and raised its 2014 forecast to $4.62.]

Pimco’s Gross explains how much investors can lose if rates rise, plus the dangers of borrowing and what investors should buy now.

Does Wyndham pay a dividend?

Cohen: Yes. It yields 1.6%. The company will enjoy operating leverage, but there could be some risks. Wyndham has a time-share business, and some other companies’ time-share operations haven’t worked out well, depending in part on where the properties were located. Wyndham also could benefit from increased business travel in 2014.

When household incomes begin to rise, deferred spending occurs first. Along with autos and housing, that means spending on food. Supermarket stocks performed well until just a few months ago, when an inflection point occurred in economic growth. Now, a lot of the household dollar is going to things like department stores.

Are restaurants considered food or fun?

Cohen: Eating away from home is in the fun category. Our analysts are recommending some dining shares, but I want to talk about Nordstrom [JWN]. The stock closed Friday at $61.11. Nordstrom underperformed much of its category and the S&P 500 last year. It was up about 11% in the past 12 months. We estimate it will earn $3.68 a share for the fiscal year ending Feb. 2, and $4.20 for the following fiscal year, which is 2% above consensus estimates of $4.11. The stock yields 2%. The company could have good operating leverage. Same-store sales are estimated to have risen by more than 3% in the current fiscal year. They could jump to more than 5% in the year ahead.

Abby Joseph Cohen: “Mexico will benefit from the improvement in the U.S.”

Nordstrom generates return on equity, on a DuPont [DD] basis, of 30% and higher. [Under the DuPont performance model, developed by the company of the same name, ROE equals net margin multiplied by asset turnover multiplied by financial leverage.]

Black: What is the P/E?

Cohen: It is 16.6 times fiscal 2013 earnings, and 14.6 times the following year’s earnings.

Rogers: Was there a particular problem at Nordstrom? Many retailers did well last year, including higher-end companies.

Cohen: Earlier in the year, high-end retailers did well. Toward the end of the year, retailers appealing to middle- and lower-middle-income shoppers did well. Nordstrom’s shares missed out, as the company isn’t decisively in either category.

My last name is Extra Space Storage [EXR], the second-largest owner of do-it-yourself storage facilities in the U.S. It has also been an underperformer. The stock was up 15% in the past 12 months. Funds from operations could rise to $2.42 in 2014 from $1.97 in 2013. The stock yields 3.4%. The category hasn’t performed well in recent months, in large part because housing was doing better. The market reasoned that if people were moving into new homes and young people were moving out of their parents’ homes, they wouldn’t need storage. Yet demand is OK, and seems to have stabilized. Also, there has been a significant slowdown in new capacity coming onstream. Finally, Extra Space Storage has done a good job of consolidating smaller operators that had problems. It has made a number of accretive acquisitions.

Is this company a real-estate investment trust?

Cohen: Yes, it is a REIT. Some potential negatives could be a rise in the cost of capital and a slowdown in average rent charged to customers.

Thank you, Abby. Let’s hear from Marc.

Faber: This morning, I said most people don’t benefit from rising stock prices. This handsome young man on my left said I was incorrect. [Gabelli starts preening.] Yet, here are some statistics from Gallup’s annual economy and personal-finance survey on the percentage of U.S. adults invested in the market. The survey, whose results were published in May, asks whether respondents personally or jointly with a spouse have any money invested in the market, either in individual stock accounts, stock mutual funds, self-directed 401(k) retirement accounts, or individual retirement accounts. Only 52% responded positively.

Gabelli: They didn’t ask about company-sponsored 401(k)s, so it is a faulty question.

Faber: An analysis of Federal Reserve data suggests that half the U.S. population has seen a 40% decrease in wealth since 2007.

In Reminiscences of a Stock Operator [a fictionalized account of the trader Jesse Livermore that has become a Wall Street classic], Livermore said, “It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It was always my sitting. Got that? My sitting tight.” Here’s another thought from John Hussmann of the Hussmann Funds: “The problem with bubbles is that they force one to decide whether to look like an idiot before the peak, or an idiot after the peak. There’s no calling the top, and most of the signals that have been most historically useful for that purpose have been blaring red since late 2011.”

I am negative about U.S. stocks, and the Russell 2000 in particular. Regarding Abby’s energy recommendation, this is one of the few sectors with insider buying. In other sectors, statistics show that company insiders are selling their shares like crazy, and companies are buying like crazy.

Zulauf: These are the same people.

Faber: Precisely. Looking at 10-year annualized returns for U.S. stocks, the Value Line arithmetic index has risen 11% a year. The Standard & Poor’s 600 and the Nasdaq 100 have each risen 9.4% a year. In other words, the market hasn’t done badly. Sentiment figures are extremely bullish, and valuations are on the high side.

But there are a lot of questions about earnings, both because of stock buybacks and unfunded pension liabilities. How can companies have rising earnings, yet not provision sufficiently for their pension funds?

Good question. Where are you leading us with your musings?

Faber: What I recommend to clients and what I do with my own portfolio aren’t always the same. That said, my first recommendation is to short the Russell 2000. You can use the iShares Russell 2000 exchange-traded fund [IWM]. Small stocks have outperformed large stocks significantly in the past few years.

Next, I would buy 10-year Treasury notes, because I don’t believe in this magnificent U.S. economic recovery. The U.S. is going to turn down, and bond yields are going to fall. Abby just gave me a good idea. She is long the iShares MSCI Mexico Capped ETF, so I will go short.

Cohen: Are you shorting Nordstrom, too?

What are you doing with your own money?

Faber: I have a lot of cash, and I bought Treasury bonds.

Gabelli: In what currency is your cash?

Faber: It is mostly in U.S. dollars. I also have Singapore dollars, and Malaysian ringgit.

Black: You have no faith in the Federal Reserve. Yet you keep the bulk of your wealth in U.S. dollars?

Faber: I have no faith in paper money, period. Next, insider buying is also high in gold shares. Gold has massively underperformed relative to the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000. Maybe the price will go down some from here, but individual investors and my fellow panelists and Barron’s editors ought to own some gold. About 20% of my net worth is in gold. I don’t even value it in my portfolio. What goes down, I don’t value.

[Laughter all around.]

I am a director of Sprott [SII.Canada]. Eric Sprott, the founder, is a smart guy who made a lot of money for himself, his funds, and charities. He sold a lot of his company’s shares because he sees better value in small mining companies. If the gold price goes up 30%, Sprott’s shares might double, but mining stocks could go up four times. We are already starting to see a move up in the stocks.

Which stocks are you recommending?

Faber: I recommend the Market Vectors Junior Gold Miners ETF [GDXJ], although I don’t own it. I own physical gold because the old system will implode. Those who own paper assets are doomed.

Zulauf: Can you put the time frame on the implosion?

Faber: Let’s enjoy dinner tonight. Maybe it will happen tomorrow.

We’ve been discussing China’s water problem. Pollution, too, has become so horrible that people are leaving China with their children. Sometimes, entire cities break down. You hardly have a clear day in Hong Kong any more, or in Shanghai. Agriculture is in disarray because the water table is falling, and agricultural commodities prices have corrected significantly, despite all the money-printing around the world.

Prices for commodities, such as soybeans, corn, and wheat, are now at reasonable levels. I am recommending Wilmar International [WIL.Singapore], an agribusiness company.

Tourism in Asia will grow, unless there is a war. I have seen Macau go from a sleepy village to a gambling center seven times the size of Las Vegas. This year, 30 million Chinese will travel to Macau. It also appeals to Thais, Indonesians, and others in the region. Chinese tourism in Thailand grew by 90% last year. How do you play this tourist boom?

Gabelli: Aircraft.

Faber: I am not keen to own Singapore Airlines [SIA.Singapore] or Cathay Pacific Airways [293.Hong Kong] because they have a lot of competition from budget airlines. But I like some airline-servicing companies based in Singapore, including SATS[SATS.Singapore], in the catering business, and SIA Engineering [SIE.Singapore], which overhauls aircraft. They have subsidiaries in many Asian countries. The stocks yield around 4%. They aren’t supercheap, and the Asian markets generally aren’t cheap enough for me. But longer term, if you want to park money in Asia, both companies will do well.

Returning to Wilmar, it specializes in palm-oil products and sugar. The founder, Robert Kuok, and his family are the controlling shareholders. It is a big family in the region.

The attitude has changed in Asia: Many family businesses used to be dishonest but now are more honest. They realized that by being relatively clean, they could earn a higher stock-market valuation. Also, the Singapore authorities are strict.

Cohen: Marc, how important to Wilmar is palm oil?

Faber: It accounts for 70% of revenue.

Cohen: The saturated-fat content in palm oil is considered highly dangerous. The food industry in the U.S. is moving away from hydrogenated fats, but especially palm oil. Aren’t you concerned about this?

Gabelli: He drinks and he smokes. What does he care?

Faber: From my studies of the food industry, everything you eat today is unhealthy.

Marc Faber’s Picks & Pans

| Investment/Ticker |

1/10/14 Price/Yield |

| LONG |

|

| 10-year Treasury Notes |

2.86% |

| Market Vectors Junior Gold Miners ETF/GDXJ |

$32.70 |

| Singapore: |

|

| Wilmar International/WIL.Singapore |

S$3.35 |

| SATS/SATS.Singapore |

3.21 |

| SIA Engineering/SIE.Singapore |

4.99 |

| Hutchison Port Hldg Trust/HPHT.Singapore |

$0.68 |

| Vietnam: |

|

| HaNoi-Hai Duong Beer/HAD.Vietnam |

41,800 VND |

| FPT/FPT.Vietnam |

48,700 |

| Vietnam Dairy Products/VNM.Vietnam |

138,000 |

| iShares Russell2000ETF/IWM |

$115.52 |

| iSharesMSCIMexico Capped ETF/EWW |

67.08 |

| Turkish lira (spot) |

$1=2.16TRY |

| MomentumStocks: |

|

| Tesla Motors/TSLA |

$145.72 |

| Netflix/NFLX |

332.14 |

| Facebook/FB |

57.94 |

| Twitter/TWTR |

57 |

| Veeva Systems/VEEV |

32.53 |

| 3DSystems/DDD |

94.45 |

Source: Bloomberg

There is a colossal bubble in assets. When central banks print money, all assets go up. When they pull back, we could see deflation in asset prices but a pickup in consumer prices and the cost of living. Still, you have to own some assets.Hutchison Port Holdings Trust[HPHT.Singapore] yields about 7%. It owns several ports in Hong Kong and China, which isn’t a good business right now. When the economy slows, the dividend might be cut to 5% or so. Many Singapore real-estate investment trusts have corrected meaningfully, and now yield 5% to 6%. They aren’t terrific investments because property prices could fall. But if you have a negative view of the world, and you think trade will contract, property prices will fall, and the yield on the 10-year Treasury will drop, a REIT like Hutchison is a relatively attractive investment.

Cohen: Under the new Chinese economic plan, there will be an increase in free-trade zones that could benefit ports other than Hong Kong.

Faber: For sure. I’m not bullish about Hong Kong port traffic. It is unlikely to grow. That is why the stock yields 7%. But the board is made up of smart people. The group, which is controlled by Li Ka-shing, the richest man in Asia, is keen on infrastructure investments around the world. They run their ports efficiently.

Felix, you are negative on Hong Kong. [Zulauf recommended in last week’s issue selling short the iShares MSCI Hong Kong ETF, or EWH.] Property companies are a big component of the Hong Kong stock market, and they are selling at 40% to 50% of asset value. Property values may fall further, but a lot of the bad news has been discounted. I would rather buy Hong Kong shares and short the Nasdaq.

Zulauf: I am short both, but you are right that Hong Kong real-estate companies sell at a discount, although it is unlikely the discount is as high as 50%.

Faber: The outlook for property in Asia isn’t bad because a lot of Europeans realize they will need to leave Europe for tax reasons. They can live in Singapore and be taxed at a much lower rate. Even if China grows by only 3% or 4%, it is better than Europe. People are moving up the economic ladder in Asia and into the middle class.

Are you bullish on India?

Faber: I am on the board of the oldest India fund [the India Capital fund]. The macroeconomic outlook for India isn’t good, but an election is coming, and the market always rallies into elections. The leading candidate, Narendra Modi…

Hickey: …is pro-business. He is speaking before huge crowds.

Faber: In dollar terms, the Indian market is still down about 40% from the peak, because the currency has weakened. In the 1970s, stock market indexes performed poorly and stock-picking came to the fore. Asia could be like that now. It is a huge region, and you have to invest by company. Some Indian companies will do well, and others poorly. Some people made 40% on their investments in China last year, but the benchmark index did poorly.

I like Vietnam. The economy has had its troubles, and the market has seen a big decline. I want you to visualize Vietnam. [Stands up, walks to a nearby wall, and begins to draw a map of Vietnam with his hands.] Here’s Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City, the border with China, and the Mekong River. And here in the middle, on the coast, is Da Nang.

South of Da Nang is China Beach, and north [still drawing] are other beaches. This was the largest American base during the Vietnam War. Coming back to tourism, there is a new airport in Da Nang with international flights. The place will be like Benidorm, the Spanish resort area, in a few years. Benidorm used to be nice, and then it became overbuilt and cheap tourism arrived. Pockets of Asia, including Indochina and India and Bangladesh, are underdeveloped. Eventually there will be road and rail links, and the area will become a giant free-trade zone. There are many investment opportunities here.

Is the Market Vectors Vietnam ETF [VNM] the best way to invest?

Faber: No, because it includes other things besides Vietnamese shares. My favorite investment is Ha Noi-Hai Duong Beer [HAD.Vietnam], a local brewery. FPT [FPT.Vietnam], an information-technology company that sells mobile phones, Internet services, and software, is another pick. It is a technology conglomerate with more value than its share price reflects.

Zulauf: Can anyone buy Vietnamese shares, or are there restrictions on ownership?

Faber: There are restrictions. Non-Vietnamese investors can’t own 100% of the shares, but in time the rules will be liberalized. The price of real estate in Vietnam is bottoming. Prices will go up, especially on the coast around China Beach. In the interest of full disclosure, my partners and I own a hotel there, and have an indirect ownership stake in another.

Vietnam Dairy Products [VNM.Vietnam] is a Vietnamese blue chip. It has been growing around 30% a year, and can continue to grow by about 20% a year. The stock hasn’t been acting well lately, but the company has a big market in Vietnam and will do well long term. Asian consumer companies aren’t cheap anymore, but in time, multinational consumer companies will want to acquire them because they have distribution in the region. A basket of Vietnamese shares could be attractive.

Anything else, Marc?

Faber: I recommend shorting the Turkish lira. I had an experience in Turkey that led me to believe that some families are above the law. When I see that in an emerging economy, it makes me careful about investing.

Lastly, I recommend shorting a basket of momentum stocks, including Tesla Motors[TSLA], Netflix [NFLX], Facebook [FB], Twitter [TWTR], Veeva Systems [VEEV], and 3D Systems [DDD]. They might be good companies, but they are overpriced.

Thanks, Marc. Nice map-making. Meryl, where are you shopping this year?

Witmer: My first pick is Wyndham Worldwide. Abby and I are on the same page. The company operates in three segments: lodging, vacation exchange and rental, and vacation ownership. The first two are fantastic businesses. Given their return on tangible assets, at more than 20%, and their prospects, they are both worth high multiples. Wyndham would be trading much higher if not for the unfair, perhaps snobbish view of the third business, more commonly known as time-shares.

The company is the largest global franchisor of hotels. It makes money on the capital other people put up. It has 15 brands in 67 countries. It was built by acquisitions, starting with Howard Johnson and Ramada in 1990. In a display of great capital allocation, management bought Microtel Inns & Suites and Hawthorn Suites in 2008 for $132 million from Hyatt Hotels [H]. They consolidated the business, which was about break-even, and got it earning $40 million in short order. It is efficient to add brands to the Wyndham hotel franchise platform. It’s a bit like servicing elevators; the denser the service area, the more profitable the business. Like most franchisor businesses, lodging requires little capital to grow organically. Incremental margins typically are in the 40% range. Capital spending in this business is around $40 million a year, and Ebitda [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization] is $300 million.

Tell us about the other businesses.

Witmer: The vacation exchange and rental business includes RCI, the leading timeshare-exchange network, and a global network of vacation rentals under different brands. It is a fee-for service business that offers leisure travelers access to a range of fully furnished vacation properties. RCI has 3.7 million members and a 65% market share. It can grow with minimal capital investment. Being the biggest in the business is important, because it makes it possible to affordably spend on technology. Wyndham has pulled ahead in the field. About 70% of time-share owners are members of exchange companies.

Meryl Witmer’s Picks

| Company/Ticker |

1/10/14 Price |

| WyndhamWorldwide/WYN |

$72.97 |

| Spectrum Brands Holdings/SPB |

69.8 |

| Esterline Technologies/ESL |

101.67 |

| Constellium/CSTM |

22.98 |

Source: Bloomberg

When we met recently with Steve Holmes, Wyndham’s CEO, he said he was most excited about the global vacation-rental business. It, too, is fee-for-service, and offers vacation-property owners the chance to rent their properties to leisure travelers. Wyndham has developed software that enables it to have dynamic pricing, which could fuel better results for homeowners and the company in coming years.

How is the time-share business doing?

Witmer: That’s the third business segment — vacation ownership. Wyndham has a quality operation and a great reputation, along the lines of Hilton Worldwide Holdings [HLT] and Disney [DIS], the other class players in the field. Many of us in the “investment class” might look down on this type of product. But for many people, vacation ownership is aspirational, and there is a feeling of pride about owning a piece of a vacation property. Wyndham is the largest player in the industry, with more than 900,000 members. Vacation ownership is a relatively economical way to guarantee a nice vacation for your family in a property that has one or two bedrooms and, typically, a kitchen and living room.

The key is, how happy are the buyers of these properties with their purchases? About 80% of initial buyers acquire additional access. I was shocked by the resilience of the business; it didn’t seem to notice the recession in 2009. Return on tangible assets, at 13.5%, isn’t as robust as in the other businesses, but it still is healthy. The segment also has some excess property. Excluding that, we estimate a 16% return on assets.

What do Wyndham’s earnings look like?

Witmer: Holmes is a great capital allocator. He is personally exposed on more than a million shares, and has never sold any. He has shrunk the shares outstanding since 2006 from 199 million to under 132 million. We’re assuming he will continue to buy in shares with free cash flow.

Reported earnings could increase in the next two to three years by about $115 million to $625 million. To that we add noncash charges of $195 million for things such as excess depreciation and amortization, to get a free-cash target of $820 million. We see the share count falling to 112 million in two years, and 103 million in three years. This adds up to after-tax free cash flow of $7.30 to $8 a share. The stock is $72.97. Putting a multiple of 13 to 15 on estimated after-tax free cash flow gives us a target price of $95 to $119 in a year or two, if it all plays out.

Gabelli: Does the company have net-operating-loss carryforwards? [Previous losses that can be used to defray taxes.]

Witmer: Yes, but they are running out, so I exclude them from my numbers.

Next, I am reiterating a 2013 pick, Spectrum Brands Holdings [SPB]. It is trading at $69.80 a share. Spectrum is a diversified branded consumer-products company. Its brands include Spectracide and Black Flag in the home-and-garden aisle, Black & Decker and George Foreman in small appliances, Remington razors, Rayovac batteries, and Kwikset and Baldwin locks. Last year my low-end estimate of free cash flow for 2015 was $7 a share. Management recently forecast that free cash flow will be at least $350 million in 2014, so with 52 million shares outstanding, Spectrum is a year ahead of my schedule. The company is investing for organic growth and making smart acquisitions to take advantage of huge NOLs [net operating losses]. It bought Kwikset in 2012, and that is working out well. It recently announced the acquisition of Liquid Fence, which has a product that works to keep deer from eating flowers and vegetables. It should fold nicely into Spectrum’s home-and-garden distribution system. Spectrum should be trading 30% higher, with potential for share appreciation, as management continues to do the right thing.

Meryl Witmer: “Wyndham Worldwide is the largest global franchisor of hotels.”

Esterline Technologies [ESL], my next pick, is $101.67 a share, and there are 31.7 million shares outstanding. It has about $500 million of net debt.

What does Esterline do?

Witmer: It manufactures highly specialized engineered products for the aerospace and defense industry. The company is organized into three segments: avionics and controls, sensors and systems, and advanced materials. Total revenue is split 45% from commercial aviation, 35% from defense, and 20% from industrial customers. The company reported $2 billion in total revenue for fiscal 2013, ended Oct. 25, of which 15% came from higher-margin aftermarket business.

The avionics and controls business is 40% of revenue. It produces cockpit paneling and systems, as well as headsets and pilot-interface controls. The sensors and systems business is 36% of revenue, and manufactures power systems, connectors, and advance sensor systems. Esterline’s sensors measure the temperature, pressure, and speed of aircraft engines. The company will be a Tier 1 supplier to Rolls-Royce [RR.U.K.] for the new Airbus [AIR.France] A400 and A350. Finally, the advanced-materials segment is 24% of revenue, evenly split among defense and engineered materials. This segment is a real gem. It produces elastomer products such as clamps and seals that have high profit margins and a large, recurring aftermarket business. It also produces the stealth materials used on the new F-35 fighter jet and other systems that distract incoming missiles.

What attracts you to Esterline?

Witmer: The company has been built in the past 15 years through a series of acquisitions. While previous management bought some terrific businesses, they were never fully integrated. As a result, operating profit margins averaged about 10%, 5% to 7% below peers. Our interest was piqued when Esterline announced that Curtis Reusser would be joining the company as CEO in October 2013. He was previously president of the aircraft-systems unit at United Technologies [UTX], joining that company after it acquired Goodrich in 2012.

Our checks on Reusser came back positive. His experience in lean manufacturing and operations really stood out. We studied his track record at Goodrich, where he increased operating margins from 2006 through 2011 to 17% from 12% in the division he ran. When asked on his first conference call as CEO whether he thought Esterline could achieve 15% operating margins compared to about 12% reported in fiscal 2013, he responded, ‘There is a lot of opportunity. Internally, I’m sure going to drive higher than that.’

How high could margins go?

Witmer: Esterline could achieve 15% operating margins in 2015. We conservatively assume flat revenue of $2 billion next year, resulting in $6.62 of earnings per share. Add back $1.80 a share in noncash amortization resulting from previous acquisitions, and you get $8.42 a share of free cash flow. We value that at 14 to 15 times, and add the $7 a share of free cash we expect the company to generate this year, to get a base target price of $125 to $133 a share, up from the current $100. With revenue growth and higher margins, free cash flow could approach $10 a share in 2016 or 2017, yielding a target price closer to $160 a share.

Gabelli: With the middle class growing in India and China, anything tied to commercial aviation in any capacity will continue to do well, and the stock market likes it.

Witmer: Let’s hope so. My last pick is Constellium [CSTM], a producer of specialized aluminum products. The company went public in 2013 at $15 a share, and is not well known. It now trades at $22.98, and there are 105 million shares outstanding, for an equity capitalization of $2.4 billion. Net debt is $225 million. The company is headquartered in the Netherlands and reports financials in euros. Yet, the shares are listed in New York. I have converted my numbers to dollars, at 1.35 euros to the dollar.

Constellium converts aluminum into specialty products. It earns a conversion spread [the difference between aluminum and finished-product prices] and has minimal exposure to the underlying aluminum prices. It produces aluminum plate for aerospace customers, can stock for beverage manufacturers in Europe, and sheet and crash-management parts for automotive manufacturers.

Gabelli: It’s Alcoa [AA] without the upstream [aluminum-mining] business, right?

Witmer: Correct. Constellium has about a million tons of rolling capacity across six major rolling facilities. It is known for its research-and-development expertise and specialized technical capabilities, which have enabled it to develop long-term relationships with key customers including Airbus, Boeing [BA], Audi, and Mercedes. These companies require suppliers’ plants to be certified, which provides barriers to competitors. We see a structural change occurring in both the aerospace and automotive markets. The demand for lighter, stronger materials that are environmentally friendly will significantly increase aluminum usage in the years ahead. That will benefit Constellium as it moves production capacity to higher-value-added products.

In aerospace, Constellium is the global leader in plate and one of only two producers with certified production plants in both North America and Europe. Parts produced using aluminum include wing-skin panels, floor beams, and landing gear. Importantly, the company has developed Airware, a lightweight aluminum lithium alloy. It is 25% lighter than competing products, and has lower maintenance costs, better durability, and recyclability. Constellium signed a 10-year contract with Airbus to use Airware on the A350, and deliveries should start in 2015. Overall, this market is expected to grow by about 10% a year.

Cohen: How does this compound compare to the alloy used in Boeing planes, such as the Dreamliner?

Witmer: It is about as light, but has better properties. It is easier to work with, and cheaper, and you can recycle the waste economically.

Gabelli: Put some numbers on this.

Witmer: I will, after I tell you about the automotive division. Constellium is the largest producer of aluminum sheet for a vehicle’s core body structure, known as Body-in-White, for the premium European auto makers. Next year could mark a significant step-change in demand in North America, with the rollout of the new Ford [F] F-150. Aluminum will account for 20% of its weight, up from 5% today. Miles per gallon could increase to an estimated 30 from 23. Other auto makers are following in Europe’s and Ford’s footsteps. By the company’s estimate, demand in North America could grow to 450,000 tons by 2015 and a million tons by 2020 from less than 100,000 in 2012. Constellium currently doesn’t sell Body-in-White in North America, but is negotiating to do so. [Constellium announced on Jan. 23 that it had formed a joint venture with UACJ(5741.Japan), a Japanese aluminum producer, to supply Body-in-White to North America.] This is being driven by federal fuel-economy regulations mandating an average of 55 miles per gallon for corporate fleets by 2025.

Now, the numbers. Constellium is expected to earn about $2 in 2013, growing at a nice clip for many years thereafter, driven by aerospace and automotive trends. It has the potential to earn more than $2.50 a share in two or three years, all while generating free cash flow. It could start to pay a dividend this year. Our price target is $30 to $35 in the next two to three years. The company estimated that the replacement value of its assets is north of six billion euros [$8.2 billion], which compares to an enterprise value of $3 billion today. We see significant upside.

Gabelli: Alcoa has the same downstream dynamics. If it spun off this business, you’d have a great investment.

Bill Gross’ Picks

| Fund/Ticker |

1/10/14 Price/Yield |

| Pimco Dynamic Income/PDI |

$29.21/11.6% |

| Pimco Muni Income Fund II/PML |

11.02/6.9 |

| Reaves Utility Income/UTG |

25.10/6.2 |

| Pimco 0-5 Year High Yield |

|

| Corporate Bond Index ETF/HYS |

106.68/4.6 |

Source: Bloomberg

Thanks, Meryl. Bill, you’re next.

Gross: Almost all assets are artificially priced to the extent that interest rates and, specifically, the policy rate [the Federal Reserve’s targeted federal-funds rate] is artificially low. Some suggest that it should be even lower [the current fed funds target is 0.25%], and perhaps negative. The Fed is engaged in quantitative easing [buying bonds] to keep rates near zero, which is artificially low relative to history and a policy rate that more closely resembles inflation. Historically, this makes it harder to know what prices should be for stocks, alternative assets, and homes.

Let’s assume the Fed finishes tapering its asset purchases by the end of this year. It will be critical for the Fed and other central banks to guide our expectations for 2015 and 2016. Some Fed governors would like to guide us back to the less-artificial prices of yesteryear. I won’t take either side here, but want to emphasize only that guidance will be important in helping private investors understand the cost of financing and allowing them a hope of making money in five-, 10-, and even 30-year bonds. Guidance is meant to induce the private market to take the Fed’s place and buy what they have been buying. The market was disrupted in May, when the taper was hinted at, and there could be further disruptions, depending on whether investors believe central banks and can accept their forward guidance.

Will the private sector pick up the slack?

Gross: I expect so. In the movie Peter Pan, Tinker Bell throws pixie dust into the air and says, “Do you believe?” The audience is supposed to say “We believe.” If the Fed ends its bond-buying program when unemployment falls to 6.5% or lower and the real economy is self-sustaining, perhaps we can exit this fairy-tale world. Some have that confidence in the Fed, and some don’t. I continue to believe in a “new normal” slower-growth world for a long time to come.

Hickey: Money-printing has been tried for thousands of years. How many successful exits have there been? Any?

Gross: I am not a defender of central banks or fiat currency. But there have been successful monetary tightenings.

Hickey: How many times can you end money-printing and get away with it, without having some kind of dislocation in the economy?

Gross: There haven’t been many big money-printing episodes in the past few centuries. The conclusion of each wasn’t pretty, although the timing here is up for grabs. If institutional investors, hedge funds, banks, and investment banks have confidence in the availability of liquidity and the cost of funding, the system will keep going.

Bill Gross: “The sweetest spot, if the curve remains steep, is five- to six-year maturities.”

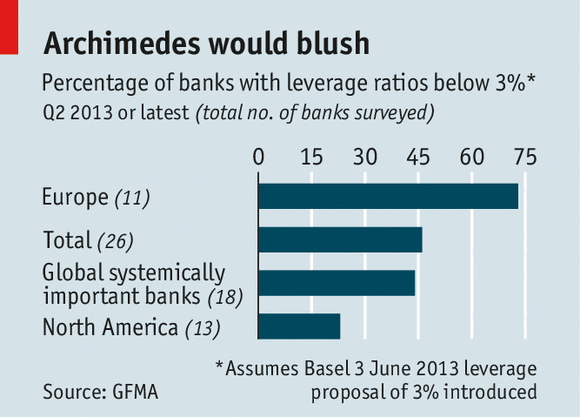

Black: The U.S. has $17 trillion of debt. Let’s say interest rates back up by 200 to 250 basis points [two to 2.5 percentage points]. Can our economy afford $340 billion to $425 billion a year in incremental interest expense?

Gross: The U.S. government can afford it. Whether households and corporations can afford it is the bigger question. The average interest cost for the government at the moment is about 2% of GDP. If you doubled that, which would take time, the deficit would increase by 2%. The government can handle it. But can a young family trying to buy a house afford a 6% mortgage?

Zulauf: If the Fed concludes its bond-buying by the end of the year, that would be a regime shift of major proportions. Wouldn’t it be an impediment to asset prices rising?

Gross: Stocks and bonds have risen in price because of the Fed’s check-writing, to the tune of a trillion dollars a year. Once that disappears, investors should wonder who is going to buy these assets. There are only two buyers: the private market and central banks. The private market dominated in 2013 with corporate stock buybacks.

If the yield curve remains steep, should investors expect price-appreciation on intermediate-term issues as they age and become shorter-term?

Gross: That’s our strategy — taking advantage of the so-called roll down. At the moment, yields are as low as 0.25% on the short end and as high as 3.75% on the long end. Investors are pricing in a significant rise in the federal-funds rate in coming years. If they are wrong and the curve remains steep, as we believe it will, a roll-down strategy will be successful.

What is the sweet spot in maturities?

Gross: The sweetest spot, if the curve remains steep, and the most dangerous spot if it doesn’t, is five- to six-year maturities. [The five-year Treasury note recently yielded 1.72%.] A barbell strategy [buying bonds at both ends of the yield curve] might be safer from the standpoint of curve risk, but it is lower-yielding. We like the fives.

I’ve chosen four picks this year that yield more than Treasuries, but are relatively “safe.” I put that in quotes. You guys have heard me quote Will Rogers, the famed Oklahoma journalist, before. He said during the Depression, ‘I’m not so much concerned about the return on my money as the return of my money.” Investors are at risk this year of not getting their money returned in all assets, not only bonds. Several of my ideas have “Pimco” in front of them, but other firms, including BlackRock [BLK], T. Rowe Price[TROW], and Invesco [IVZ], have similar vehicles offering excellent opportunities.

Rogers: Thanks for the advertisement, but let’s have the names.

Gross: My first recommendation is a new closed-end fund, Pimco Dynamic Income[PDI]. It was launched in May 2012 when interest rates were close to bottoming and prices were near their highs. Despite that, its price is nearly 20% higher than the original offering. PDI is slightly levered, which is one advantage. It borrows at repo [repurchase agreement] rates of about half a percentage point and invests at higher yields. The fund is managed by Daniel Ivascyn and others. By the time these comments are published, Ivascyn and Alfred Murata, co-managers of Pimco Income [PIMIX], will have been named Morningstar’s Fixed Income Managers of the Year.

Witmer: Is that a positive or negative indicator?

Gross: There are no guarantees, but Morningstar has given top honors to many Pimco managers. [Ivascyn got another honor last week; in the wake of CEO and Co-Chief Investment Officer Mohamed El-Erian’s surprise resignation, he was named Pimco’s deputy chief investment officer. Gross told Barron’s the firm’s new leadership team “has my full confidence. We had a good year in 2013, despite outflows from Pimco Total Return (PTTAX; the world’s largest bond fund, run by Gross), and I’m going to be here as long as they’ll have me.”]

Dynamic Income invests in nonagency securities and some corporate bonds. “Nonagency” is industry code for subprime [securities with low credit ratings]. The subprime market trades at a steep discount to par, and in the past two years has delivered an equity-like total return. The fund yields 7.85%, but it paid a special dividend that produced an annualized yield of 12%. The fund could have a lot of firepower if the housing market holds up. It trades at a 5% discount to net asset value. In a world of 4% to 5% yields on “junk” bonds, this is a high-yield alternative that has gone unappreciated by the market.

For those interested in tax-free income, Pimco Municipal Income Fund II [PML] is a national fund. It yields 7%.

Does it hold any Puerto Rico or Detroit debt?

Gross: No. It sells at a 1% discount to net asset value, and is a long-term bond investment — a negative, considering my earlier comments. In the muni market, however, you have to go beyond five years to find yield.

Third is something I’ve recommended in years past. It worked out well for those who like utility stocks, which yield around 4% to 4.5%. The fund is Reaves Utility Income[UTG], a closed-end. The fund is approximately 50% levered, so you get one-and-a-half times the kick in returns, although the kick can be in the pants if interest rates rise. The largest holdings are Verizon Communications [VZ] and AT&T [T].

Gabelli: Why do they still call those utilities?

Hickey: In the old days, you had your electric utilities, your communications utilities…

Gabelli: That was back in 1940s, when they used to call pants trousers. I have no problem with this fund, but these are not the utilities of old that earned a regulated return on capital.

Gross: The fee is high on this fund, at 1.2% of assets. But it gets flushed out with the dividend yield.

Witmer: It’s a good business for the fund-management company.

Gabelli: Bill, what do you do with your own money?

Gross: I own some Reaves Utility Income and Pimco Dynamic Income. I own lots of closed-end funds that sell at discounts to net asset value and borrow money in the current environment.

Faber: Do you think there’s a chance, as I do, that the Fed will increase its asset purchases in the next two years, to $200 billion a month?

Gross: Only in your world, although I don’t completely discount your outlook for gloom and doom.

My last recommendation is the Pimco 0-5 Year High-Yield Corporate Bond Index[HYS], a high-yield ETF. The market capitalization is $3.5 billion. Its maturities are five years or less, whereas many high-yield bonds are 10 years, plus or minus. If spreads widen, 10-year bonds are at greater risk. Companies in the high-yield space include Ally Financial [GOM] and primarily BB-rated securities

Do you have any recommendations in emerging markets?

Gross: Like many here, we are invested in Mexico. We like the economy. Mexico has roughly half the debt of the U.S. The government is initiating reforms. Interest rates on 10-year securities are in the 5% to 6% area, but the policy rate is 4.5%, so there is currency risk. We don’t like other markets at the moment. If global markets sell off, money will move back to safe havens, namely the U.S. Given the risks, we’re staying close to home.

Black: Bill, do you expect Janet Yellen [incoming Federal Reserve chair] and Stanley Fischer [incoming vice chair] to have a harmonious relationship?

Gross: Fischer [former governor of the Bank of Israel] is the central bankers’ central banker. He taught Bernanke and Mario Draghi [president of the European Central Bank]. There is always the possibility of friction when the second-in-command is so prominent, but I don’t expect any. Fischer and Yellen have similar policies and views on guidance. Fischer, though a leader, is a team player. But let’s ask Abby, who knows him.

Cohen: I agree wholeheartedly with Bill. I expect Fischer to be a gracious and supportive colleague at the Fed.

Gross: And that is probably what the Fed needs at this difficult time.

Well said. Thank you, Bill.