Why Other Countries Teach Better

December 20, 2013 Leave a comment

December 17, 2013

Why Other Countries Teach Better

Millions of laid-off American factory workers were the first to realize that they were competing against job seekers around the globe with comparable skills but far smaller paychecks. But a similar fate also awaits workers who aspire to high-skilled, high-paying jobs in engineering and technical fields unless this country learns to prepare them to compete for the challenging work that the new global economy requires.

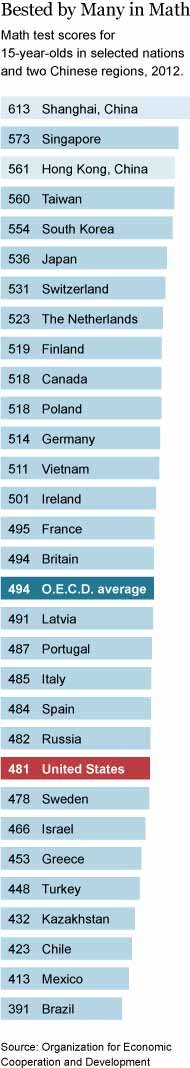

The American work force has some of weakest mathematical and problem-solving skills in the developed world. In a recent survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a global policy organization, adults in the United States scored far below average and better than only two of 12 other developed comparison countries, Italy and Spain. Worse still, the United States is losing ground in worker training to countries in Europe and Asia whose schools are not just superior to ours but getting steadily better.

The lessons from those high-performing countries can no longer be ignored by the United States if it hopes to remain competitive.

Finland: Teacher Training

Though it dropped several rankings in last year’s tests, Finland has for years been in the highest global ranks in literacy and mathematical skills. The reason dates to the postwar period, when Finns first began to consider creating comprehensive schools that would provide a quality, high-level education for poor and wealthy alike. These schools stand out in several ways, providing daily hot meals; health and dental services; psychological counseling; and an array of services for families and children in need. None of the services are means tested. Moreover, all high school students must take one of the most rigorous required curriculums in the world, including physics, chemistry, biology, philosophy, music and at least two foreign languages.

But the most important effort has been in the training of teachers, where the country leads most of the world, including the United States, thanks to a national decision made in 1979. The country decided to move preparation out of teachers’ colleges and into the universities, where it became more rigorous. By professionalizing the teacher corps and raising its value in society, the Finns have made teaching the country’s most popular occupation for the young. These programs recruit from the top quarter of the graduating high school class, demonstrating that such training has a prestige lacking in the United States. In 2010, for example, 6,600 applicants competed for 660 available primary school preparation slots in the eight Finnish universities that educate teachers.

The teacher training system in this country is abysmal by comparison. A recent report by the National Council on Teacher Quality called teacher preparation programs “an industry of mediocrity,” rating only 10 percent of more than 1,200 of them as high quality. Most have low or no academic standards for entry. Admission requirements for teaching programs at the State University of New York were raised in September, but only a handful of other states have taken similar steps.

Finnish teachers are not drawn to the profession by money; they earn only slightly more than the national average salary. But their salaries go up by about a third in the first 15 years, several percentage points higher than those of their American counterparts. Finland also requires stronger academic credentials for its junior high and high school teachers and rewards them with higher salaries.

Canada: School funding

Canada also has a more rigorous and selective teacher preparation system than the United States, but the most striking difference between the countries is how they pay for their schools.

American school districts rely far too heavily on property taxes, which means districts in wealthy areas bring in more money than those in poor ones. State tax money to make up the gap usually falls far short of the need in districts where poverty and other challenges are greatest.

Americans tend to see such inequalities as the natural order of things. Canadians do not. In recent decades, for example, three of Canada’s largest and best-performing provinces — Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario — have each addressed the inequity issue by moving to province-level funding formulas. As a recent report by the Center for American Progress notes, these formulas allow the provinces to determine how much money each district will receive, based on each district’s size and needs. The systems even out the tax base and help ensure that resources are distributed equitably, not clustered in wealthy districts.

These were not boutique experiments. The Ontario system has more than two million public school students — more than in 45 American states and the District of Columbia. But the contrast to the American system could not be more clear. Ontario, for example, strives to eliminate or at least minimize the funding inequality that would otherwise exist between poor and wealthy districts. In most American states, however, the wealthiest, highest-spending districts spend about twice as much per pupil as the lowest-spending districts, according to a federal advisory commission report. In some states, including California, the ratio is more than three to one.

This has left 40 percent of American public school students in districts of “concentrated student poverty,” the commission’s report said.

Shanghai: Fighting Elitism

China’s educational system was largely destroyed during Mao Zedong’s “cultural revolution,” which devalued intellectual pursuits and demonized academics. Since shortly after Mao’s death in 1976, the country has been rebuilding its education system at lightning speed, led by Shanghai, the nation’s largest and most internationalized city. Shanghai, of course, has powerful tools at its disposal, including the might of the authoritarian state and the nation’s centuries-old reverence for scholarship and education. It has had little difficulty advancing a potent succession of reforms that allowed it to achieve universal enrollment rapidly. The real proof is that its students were first in the world in math, science and literacy on last year’s international exams.

One of its strengths is that the city has mainly moved away from an elitist system in which greater resources and elite instructors were given to favored schools, and toward a more egalitarian, neighborhood attendance system in which students of diverse backgrounds and abilities are educated under the same roof. The city has focused on bringing the once-shunned children of migrant workers into the school system. In the words of the O.E.C.D, Shanghai has embraced the notion that migrant children are also “our children” — meaning that city’s future depends in part on them and that they, too, should be included in the educational process. Shanghai has taken several approaches to repairing the disparity between strong schools and weak ones, as measured by infrastructure and educational quality. Some poor schools were closed, reorganized, or merged with higher-level schools. Money was transferred to poor, rural schools to construct new buildings or update old ones. Teachers were transferred from cities to rural areas and vice versa. Stronger urban schools were paired with rural schools with the aim of improving teaching methods. And under a more recent strategy, strong schools took over the administration of weak ones. The Chinese are betting that the ethos, management style and teaching used in the strong schools will be transferable.

America’s stature as an economic power is being threatened by societies above us and below us on the achievement scale. Wealthy nations with high-performing schools are consolidating their advantages and working hard to improve. At the same time, less-wealthy countries like Chile, Brazil, Indonesia and Peru, have made what the O.E.C.D. describes as “impressive gains catching up from very low levels of performance.” In other words, if things remain as they are, countries that lag behind us will one day overtake us.

The United States can either learn from its competitors abroad — and finally summon the will to make necessary policy changes — or fall further and further behind. The good news is that this country has an impressive history of school improvement, as reflected in the early-20th-century compulsory school movement and the postwar expansion, which broadened access to college. Similar levels of focus and effort will be needed to move forward again.

December 17, 2013

Q. & A. With Arthur Levine

Arthur Levine, the former president of Columbia University’s Teachers College, is a longtime critic of the quality of teacher preparation in the United States. In 2006, he wrote a report describing extremely low standards for admission and graduation from teaching programs. “Teacher education right now is the Dodge City of education, unruly and chaotic,” he said at the time. Now, as the president of the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, which supports scholarship and public service in a variety of fields, he remains focused on improving the achievement gap in education among races and incomes. The foundation has given stipends to nearly 1,000 teaching fellows who have gone on to teach in the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math) in high-needs public schools. He spoke recently to David Firestone of The New York Times Editorial Board about international competitions that show both students and teachers in many countries to be better prepared than those in the United States.

Many critics of these international competitions say it’s unfair to compare test results from homogeneous countries to a diverse country like the United States. Do you think these test comparisons are legitimate, and should the United States be concerned that it is not performing better?

I think the comparisons are important. We live in a world in which our children aren’t competing for jobs against people in the next town — they’re competing for jobs against people in other countries. It’s critical that we understand how our students compare to those students. The future of this country, in an information society, is dependent on how well we do in comparison to other countries. When we were an industrial society, what mattered was labor and natural resources. We now live in an information economy in which what matters are brains and knowledge. So those tests are critically important.

Why are Asian countries always clustered in the top ranks?

They are countries that start earlier. They work longer. They work better. They just do a better job of educating kids in those areas than we do.

Should we be trying to emulate their methods, or do you think much of what they do wouldn’t work in the United States?

I think some things work and some that don’t, and they’re culturally specific. We’d be foolish not to try to learn from what they do and see what’s worthy of importing.

And one of those things is clearly starting earlier.

Kids are capable of learning about mathematics much earlier than we thought. Yes, we can begin earlier, but we also need to spend more time on those subjects, and make them more comprehensible to students. We don’t do well in that. We have much to learn from those countries about when to teach math and science, how long to teach it, and the best ways to teach it.

Finland has been near the top in many competitions, in part because of its intense focus on teacher preparation. What do they do better in that regard than we do?

I took my board to Finland two or three years ago. And what we found was that they do some things we can’t emulate, like their limits on the number of people who can enter into their teaching programs, which are tied to the labor market. So if they need a small number of math teachers, they prepare a small number of them. But they get the top people in the country who are interested in studying it. In contrast to the United States, where there’s no tie between who we prepare in our schools and our labor market needs. We produce too many teachers and so the entrance requirements come down. We’re also overproducing elementary school teachers and underproducing STEM teachers. Those are some of the things we can learn.

It’s really striking to see how much more prestige the profession of teaching has in Finland and many other countries. Can we do anything about that, other than paying more?

Paying more is an important issue, but in Finland they don’t pay more. It’s simply a higher status profession. We can make it a more selective profession, by taking only the top of those who apply. If we were able to improve working conditions for teachers, and the leadership they find in their schools, and their freedom to teach and the professional development they receive, the job would be more appealing. Increasing selectivity raises stature and increases retention.

You’ve done a lot of work on the shockingly low quality of education schools in this country, and the National Council on Teacher Quality recently described a culture of mediocrity in preparing American teachers. How bad is it?

The problem is not that higher ed isn’t capable of preparing teachers well, it’s just that it hasn’t done it, and it needs to. These programs need serious repair, but it can be done.

Our foundation created a scholarship program in five states, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, New Jersey and Georgia, where we form a coalition with the governor, the state education officers, legislators, and unions. We recruit teachers with STEM backgrounds and ask them to take a one-year master’s degree. At a participating university, we give them a fellowship of $30,000, and they agree to teach in-state for a minimum of three years. Then we tell the universities that we want them to replace their existing STEM teacher education program with one that is highly selective and focused on learning in the classroom where their graduates are going to teach.

The end result is 23 universities that have changed their teacher education programs in the way we’ve asked them to do. They’ve created very effective programs.

Given that work, and groups like 100K in 10, which has set a goal of 100,000 new STEM teachers in 10 years, are you encouraged about the future of STEM teaching?

I am. Governors are committed to STEM, because the future of their states depends on it. This is an issue of economic development — there are jobs that are going unfilled, because we don’t have the labor power to fill them. Whether states attract industry and business depends on the quality of their labor force. So they have to do this. It’s big political pressure. And the standards are going up for teacher accreditation — you now have to have a B average to get into a teacher education program, and be in the top third on standardized tests.

I’m no Pollyanna, but I’m very hopeful. It is doable. It’s just a question of will.