Smart beta-blocking; The ugly truth about smart beta

December 22, 2013 Leave a comment

| Dec 06 13:57 | 4 comments | Share

We are big fans of index tracking, particularly for those cash strapped and socially sensitive large pension funds, and we are far from alone: passive is massive for a reason. But where there’s a fee there’s a way. As alternative investments suffer the slowzombification of poor performance, active managers have been trying to find a way into this passive game, prompting some elegant demolition.First there was the list of Clifford Asness who, in a rant at the world’s refusal to be sensible (we sympathise), presented pet peeve number six:

If you deviate markedly from capitalisation weights, you are, by definition, an active manager making bets. Many fight this label. They call their deviations from market capitalisation—among other labels—smart beta, scientific investing, fundamental indexing, or risk parity…

You can believe your strategy works because you’re taking extra risk or because others make mistakes, but if it deviates from cap weighting, you don’t get to call it “passive” and, in turn, disparage “active” investing.

Then hot on his heels arrives the latest from James Montier of GMO, a weighty demolition of several forms of snake oil.

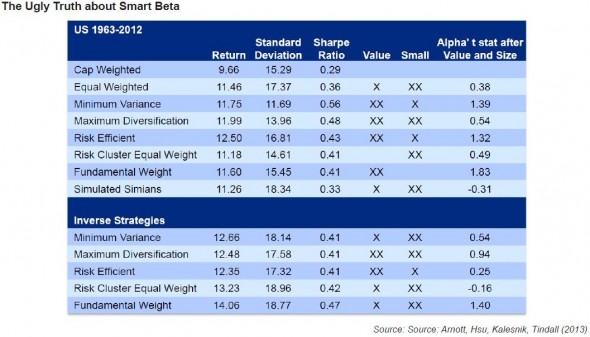

First up is the smart beta crowd, who have really just been taking bets on small companies and value stocks. As movement of the S&P500 is dominated by very large companies, doing things like equal weigh investing – putting the same amount into each of the 500 S&P companies, for instance – produces outperformance.

There are also things like minimum variance, maximum diversification, etc, but we won’t bother explaining them because, as Montier says:

The unifying trait of these approaches is that they build portfolios with indifference to price (i.e., they ignore market cap in portfolio construction). Such a process essentially guarantees there will be a value and a small cap tilt to the portfolio.

As Exhibit 3 shows, when these strategies are corrected for their exposure to “value” and “small,” they exhibit no statistically significant outperformance compared to the cap weighted benchmark. In other words, the fact that smart beta has outperformed has nothing to do with the story told (i.e., better covariance matrix, exploiting index hugging, or contra trading against the cap weighted benchmark), it is simply that they embed exposure to value and small, two traits known to have outperformed over time.

Indeed, work by Rob Arnott and friends at Research Affiliates informs the bottom half of that table. Doing the opposite of the strategies advocated by smart beta types outperform the market as well – remind us again what you’re selling here…

Montier also dismisses quality, the newest fad.

Let us be clear that there is no magic to owning quality. There are only two interesting features about “quality.” The first is of interest to economists, and that is that oligopoly appears to be a common industrial structure, as evidenced by the very slow mean reversion of the profitability of quality stocks.

So buy the stocks when they are cheap, and not when they are expensive. Recently, they have been cheap, hence the success.

From a house that has long taken a dim view of the leverage inherent in risk parity,(the antithesis of everything we at GMO hold dear) there is also good stuff on letting leverage into the process by using risk factors as a basis for judgement.

This one of the dangers of modern portfolio theory – in the classic unconstrained mean variance optimisation, leverage is seen as costless (both in implementation and in its impact upon investors). The risk factors approach exploits this oversight.

As I have written many times before, leverage is far from costless from an investor’s point of view. Leverage can never turn a bad investment into a good one, but it can turn a good investment into a bad one by transforming the temporary impairment of capital (price volatility) into the permanent impairment of capital by forcing you to sell at just the wrong time. Effectively, the most dangerous feature of leverage is that it introduces path dependency into your portfolio.

There follows another assault on risk parity and all that Ray Dalio holds dear, which isworth a read in itself, but remember that GMO isn’t attacking active management, just those trying to sell it as something which it is not.

What GMO is selling is active management at the asset class level, and so there is is another message tucked in there: value and small cap may struggle, because US equities as a whole are challenged.

As Ben Inker explained last month

the U.S. stock market is trading at levels that do not seem capable of supporting the type of returns that investors have gotten used to receiving from equities.

One part of that is the familiar story of unusually high US profit margins, here displayed as return on sales for the S&P 500:

Another is that a bout of corporate investment that spurred the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s seems unlikely.

In fact, don’t look to GMO for much in the way of optimism. They have been cautious on bonds for a long time now, and as for their enthusiasm for non US stocks, well…

To be clear, we don’t consider non-U.S. equity markets a screaming buy. But as value managers listening for any assets, anywhere, that are screaming to be bought, the world currently sounds a deathly quiet place. The hoarse whisper of “buy me” coming from European and emerging equities (as well as the polite cough for attention coming from U.S. high quality stocks) comes through loud and clear. For the purpose of doing the right thing by our clients, our major worry today is about whether our straining ears are hearing the whispers of the least overvalued equities as louder than they really are and that we consequently own more of them than is warranted. The “risk” that the U.S. stock market is significantly more attractive than we estimate it to be strikes us, by contrast, as a low probability, as well as one that is exceedingly unlikely to hurt our clients’ portfolios.