Curbs Following Singapore Riot Criticized; Security Measures Imposed on Ethnic Indian District Have Divided Public Opinion

December 27, 2013 Leave a comment

Curbs Following Singapore Riot Criticized

Security Measures Imposed on Ethnic Indian District Have Divided Public Opinion

CHUN HAN WONG

Dec. 25, 2013 10:46 p.m. ET

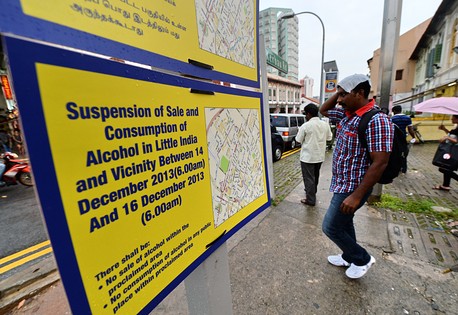

A notification of the suspension of sale and consumption of alcohol in the Little India district in Singapore.

SINGAPORE—Even as weekend crowds return to Singapore’s ethnic Indian district, where foreign workers staged a rare riot this month, the security measures imposed on the area have divided public opinion over the country’s treatment of its large migrant workforce.Scores of armed police, new surveillance cameras and curbs on alcohol sales and drinking helped keep Little India peaceful on Sunday as thousands of South Asian workers flocked to their favorite hangout. Many businesses—badly hit after hundreds of workers, angered by a fatal road accident, rioted on Dec. 8—reported improving revenues, while residents credited tightened security for restoring calm after Singapore’s worst outburst of public violence in over 40 years.

But the new public-order measures have also drawn flak from labor activists and researchers, who say the curbs could deepen fissures between citizens and the legions of low-wage foreign workers that underpin this Southeast Asian economy. Policy makers, they say, should consider broader reforms that address deep-seated grievances among migrants.

“The government’s post-riot measures are too narrowly focused on security,” said Charan Bal, a university lecturer who researches migrant-labor politics. “The riot needs to be framed within the broader context of rising migrant-labor unrest in the country—wildcat strikes, sit-ins, individual acts of protests—over grievances like working conditions, leisure spaces, and so on.”

“These grievances can, again, escalate into episodes of unrest during moments of crisis,” Mr. Bal said.

Tightly regulated Singapore, known for its safe streets and family friendly living, has long grappled with how to provide for its low-wage migrant workers, who have grown increasingly disquiet in recent years. Some have resorted to protests against what they see as exploitation by employers, including a rare and illegal strike last year by about 170 bus drivers hired from China.

About 1.3 million foreigners, including nearly one million unskilled laborers who take up menial jobs usually shunned by citizens, work in this country of 5.4 million people. South Asian migrants, who number in the hundreds of thousands and dominate low-wage sectors like construction, frequent Little India on weekends to partake in the ethnic enclave’s eclectic mix of commerce and cuisine.

Roughly 400 workers from South Asia were involved in the riot, which took place after anIndian national was crushed to death under a private bus driven by a Singaporean man, police said. Government officials have called the violence an “isolated incident,” citing alcohol as a possible factor and playing down potential links to unhappiness over living and working conditions.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who has ordered an official inquiry into riot, said authorities will study the immediate causes of the violence before considering a broader review of social and population policy. “I do not accept that we must straight away ask whether fundamental approaches or the whole way our society is organized needs to be rethought immediately,” Mr. Lee told local media this week.

“There is nothing thus far to suggest that [the rioters] have existing employment and workplace issues,” Acting Manpower Minister Tan Chuan-Jin wrote on his Facebook page this month. Nonetheless, “we will continue to do more to look after the foreign workers in Singapore,” he said. The Manpower Ministry, which regulates labor issues, declined to offer fresh comment.

Meanwhile, authorities have imposed “interim” security measures in Little India—increased police patrols and restrictions on alcohol sales and consumption—that will be in force until a government-appointed panel recommends longer-term steps by June. To reduce Sunday crowds, authorities slashed by half private-bus services that shuttle foreign workers to and from Little India, and pledged to improve amenities and organize more leisure activities at workers’ quarters.

Some migrants have bristled at the measures.

“Expecting [foreign workers] to stay and find recreational activities within the dormitories would be almost like placing them under house arrest,” said A.K.M. Mohsin, editor of a Bengali-language newspaper distributed to Bangladeshi workers in Singapore.

“Little India is a home away from home. It is the only place where they can remit money, buy familiar foods, and socialize with friends and relatives,” he added.

Security concerns have long plagued Little India, an oddity in order-obsessed Singapore, where masses of foreign workers and backpacking tourists frequent colonial-era shophouses to buy everything from jewelry and textiles to groceries and mobile devices. On weekends, migrants pack the area’s eateries and open spaces, chatting over snacks and drinks, and routinely jaywalk across the streets.

Such boisterousness has annoyed residents, who since the 1990s have lobbied officials to curb excesses like public drunkenness, littering and spitting. Authorities responded by making Little India one of Singapore’s most heavily policed districts, installing surveillance cameras and engaging auxiliary police officers—from state-owned security firm Certis CISCO—to patrol residential areas.

This has fostered resentment among foreign workers, who complain that auxiliary officers appear to target South Asians with frequent identity checks and reprimands for petty offenses. “Many men see this as a form of harassment,” Mr. Mohsin said.

Certis CISCO, which has deployed officers in Little India since early 2009, didn’t respond to requests for comment, but police officials said auxiliary officers have improved security in Little India and curbed “social dis-amenities” such as public urination and littering.

With heightened police presence in Little India likely to stay for the coming months, the added scrutiny could further alienate foreign workers already discomfited by existing measures, activists say.

“These things add up to a Singapore that is moving toward a segregationist arrangement, whereby some people have their freedoms restricted in significant ways,” said Alex Au, an activist with Transient Workers Count Too, a migrant-labor advocacy group. “This can cause side effects that we may come to regret.”

Even so, business owners believe that Little India will soon recover its usual bustle. “We expect things to improve in coming weeks,” said Mateen Ahmed, who runs a restaurant on the street where the riot broke out. “I don’t think this will have any permanent impact on the area.”