New Kind of Stress Tests Big-Bank Outlook

December 30, 2013 Leave a comment

New Kind of Stress Tests Big-Bank Outlook

DAVID REILLY

Dec. 29, 2013 7:55 p.m. ET

What is the endgame? That question is being raised more and more by bankers trying to assess the flood of new regulation continuing to wash over their firms. They will keep asking it in 2014 as even more rules are finalized and new ones crop up.

While many bankers are resigned to the fact their business will be very different due to the financial crisis, they are unsettled by the lack of an overarching framework for the multitude of regulatory initiatives. Having brought much of this on themselves, it is tough to feel sympathetic. Yet they do have a point.

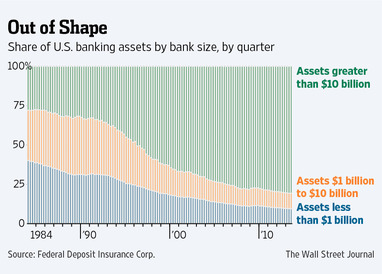

Regulators and politicians have spoken about the need to make the financial system safer and end the threat posed by too-big-to-fail banks. What they haven’t done is clearly articulate what they actually want the financial system, and big banks, to look like.

Most have rejected the idea of breaking up the biggest banks or of placing size limits on them. Absent such steps, it isn’t clear how regulators will end the too-big-to-fail issue, other than saying that it has been dealt with, a notion many rightly dispute.

So it is tough for banks and investors to gauge what they should be driving toward. Will, for example, big banks be treated as utilities with returns effectively capped by capital rules that become more stringent based on firm size?

That wouldn’t be a terrible thing; there are successful, publicly traded utilities. But investors would be better served knowing this was where things were headed. Currently, there is a feeling too-big banks will receive utility-like treatment, but investors can’t be sure.

The uncertainty doesn’t end there. While investors and banks know regulators want firms to hold more capital, there isn’t enough clarity about which measures will take precedence. For some time, banks and investors have focused on Tier 1 common ratios under new Basel III rules. Now banks also may face higher leverage ratios. And there are liquidity requirements and looming net-stable-funding rules, both of which try to address the resources banks have to withstand runs.

All these intersect, though, and sometimes conflict. Liquidity requirements necessitate banks holding more cash. That doesn’t affect Tier 1 common ratios; the calculation effectively excludes cash. Not so the leverage ratio. The end result: Banks are told to hold more cash, but this inhibits their growth and so potential profitability.

Also, within the leverage ratio, firms face a lower threshold for a bank-holding company and a higher one for a bank subsidiary. Yet bank-holding companies are supposed to be a source of strength for bank subsidiaries, not the other way round.

Amid the confusion, a new reality is dawning on banks: that none of these requirements may actually matter that much. The real measure they will be judged against, and so run their businesses to, are the results of “stress tests” administered by the Federal Reserve. These are the basis for decisions on whether banks can return capital to shareholders. Banks in early January will submit capital plans to the Fed for review.

The stress tests have become a vital regulatory tool. And the Fed has understandably kept their workings close to its vest to keep banks from trying to game them.

The unintended consequence may be that investors have no real way of knowing how a bank is doing in terms of managing toward these tests. Banks don’t, for example, tell their investors how much in capital returns they requested, only whether their plans were approved.

Even worse, with a limited view into these tests and without knowing regulators’ ultimate aim for big banks, investors are being told to simply trust in the Fed.

Getting to a safer financial system surely starts with banks. It will have to end, though, with a clearer vision for them.