The Raspberry Pi computer – how a bright British idea took flight; Cambridge scientists thought their £30 computer might find 1,000 customers. Two years on, they have shipped 2.5m units

April 7, 2014 Leave a comment

The Raspberry Pi computer – how a bright British idea took flight

Cambridge scientists thought their £30 computer might find 1,000 customers. Two years on, they have shipped 2.5m units

The Guardian, Sunday 9 March 2014 22.31 GMT

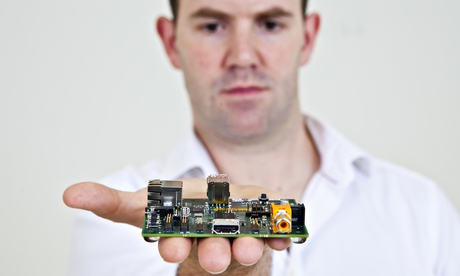

Eben Upton and Raspberry Pi computer. Photograph: Antonio Zazueta Olmos

In the end, it took just over 10 months for Felix Baumgartner‘s skydiving record from 24 miles to be broken. With considerably less publicity, a small cuddly toy named Babbage fell from a height slightly above the Austrian’s achievement after ascending to the stratosphere in a hydrogen-filled balloon.

The elaborate skydive to a field in Berkshire was accomplished using credit card-sized Raspberry Pi computers which released the toy from the balloon when it reached 31 metres above Baumgartner’s record and filmed the descent.

It is just one of a multitude of unique projects the bare-boned machine has been used for.

Launched in February 2012, more than 2.5m of the computers – which cost about £30 – have now been sold around the world, a prodigious landmark considering the group of scientists behind it thought they might sell 1,000 at most.

“If you told me I was going to sell 10,000 I would have called bullshit on that,” said Eben Upton, co-founder of the Raspberry Pi and the public face of the mini-computer.

The idea came in 2006 after Upton and some colleagues in the computer laboratory in Cambridge University shared concerns over their Friday beers at the decline in the number and skills of students applying for computer science classes.

Now 35, Upton’s digital education began with a BBC Micro home computer, learning programming languages via books and being encouraged by enthusiastic teachers.

He then went on to study physics at Cambridge after a year at IBM in a pre-university programme, where he became adept at experimenting with and reprogramming computers.

When he became director of studies in computer science in Cambridge in 2004, Upton found A-level graduates no longer had his hobbyist experience when coming to university.

PCs and games consoles had replaced the easily programmable machines of his youth, while schoolchildren were being taught to use word processors and spreadsheets instead of the code that created them.

Coupled with this was a drop in applicants from the end of the dotcom boom.

“I swear they are still as bright as they ever were. The creme de la creme are still as bright but the problem is that they have not had the experience [of reprogramming computers]. They are deprived of the experience,” he said.

“I want us to have a functioning first-world economy when I am old to pay my state pension and we are not going to have one unless we have engineers.

“It was more just this sense of sadness because we have this culture, particularly in the UK … we have this engineering culture and we had this amazing thing and then it just went away.

“When we weren’t looking, it went away and you could just see that children playing with computers had just gone away and then the adult hobbyist scene was going to go away because if you don’t feed it, these things die and it was just this really sad feeling.

“The computer went away and a decade later, the students went away.”

Talking over chess on their Friday afternoon “happy hours” in the lab, Upton and his colleagues decided to develop an affordable computer on which children could learn to program.

The group soon expanded to include local business people and by 2011 – after various different incarnations of the Pi – they came up with a computer deemed worthy of putting into production using hardware from Broadcom, the semiconductor giant where Upton is a chip architect.

A short video shown on YouTube detailing how they planned to sell the computer for $25 (£15) garnered 600,000 views, and in turn an urgency to produce the machine, which he described as “horrific”.

In February 2012, orders were taken from the public and in March, the first major delivery of 1,950 Raspberry Pi computers arrived on a palette from China.

“I got one out and plugged it into a telly and it worked and I got another out of a different box and that one worked as well. I turned to one of the trustees and said ‘We’ve made a computer company’. We were just grinning from ear to ear. They all worked and they were all perfect,” Upton said.

The computers themselves are no-nonsense in design and presentation. There are USB ports for a keyboard and mouse, an Ethernet port for the internet, a slot for a memory card and a port to connect the computer to a TV. The operating software is a form of the open-source Linux system.

Production was passed over to two British firms which now pay a royalty for each Pi sold. On the first day alone, 100,000 were sold. By October 2012, 1m had been manufactured in Britain, production having transferred from Asia. The biggest market is the United States, where 30% have gone.

About 20% are in Britain, another 30% in the rest of Europe – mostly Germany – while the rest have mostly gone to Japan and Korea. More than 400,000 of the 2.5m sold are thought to be in the hands of children, while most of them go to adult hobbyists.

The organisation behind the Pi is split: a trading company updates the engineering and delivers profits to a foundation which spends it on grants, lobbying and partnerships – 15,000 of the computers were given to schoolchildren for free last year in a deal with Google.

So far the Pi has been used by hobbyists for everything from creating a 3D scanner and calibrating temperatures for home brewing to a laddish invention which orders a pizza on the internet via the touch of one outsized button.

“In terms of our initial goals, absolutely [we are happy] because this is an organisation which thought it would sell 1,000 computers. That was the scale of the ambition. If you get them to the right kids, then you only need 1,000 computers if you target them well enough,” Upton said.