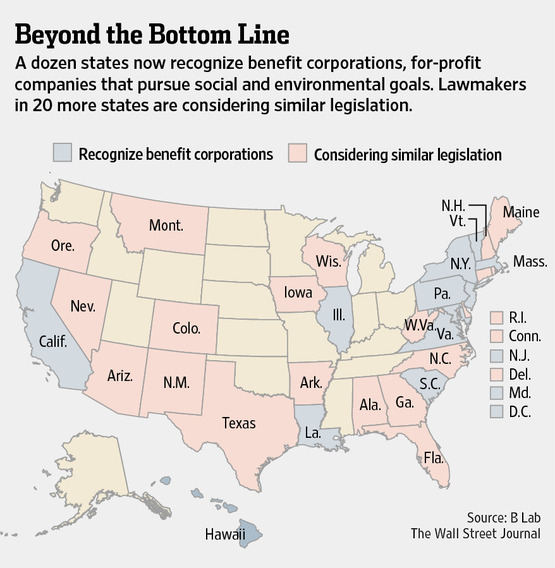

Can Firms Aim to Do Good if It Hurts Profit? A dozen states now recognize benefit corporations, for-profit companies that pursue social and environmental goals

April 11, 2013 Leave a comment

April 10, 2013, 8:23 p.m. ET

Can Firms Aim to Do Good if It Hurts Profit?

Investors Could Sue, Citing Corporate Governance Laws, but Some States Are Providing Cover Via Benefit Corporations

By ANGUS LOTEN

Blake Jones of Boulder, Colo., is one of the many modern entrepreneurs who say their goals extend beyond increasing the bottom line to such pursuits as reducing child poverty or protecting the environment. But he worries that embracing a mission other than maximizing profits could open the door to shareholder lawsuits because of decades-old corporate governance laws.

A co-founder and chief executive of Namaste Solar, Mr. Jones says his eight-year-old company gives 20% of its annual after-tax profits to local projects, such as a nearby children’s museum and a bicycle-recycling program. It also offers up to $30,000 in solar-system installation grants to schools and other nonprofits. But “according to state law,” he says, “we don’t have any legal protection for doing business the way we do” even though such practices attract customers who also “want to do good.”

A dozen states in the past three years, including New York and California, have adjusted their incorporation laws—the same laws that set the “Inc.” or the “Co.” after a company name—to create a new corporate structure known as a benefit corporation. These structures seek to provide some legal cover for entrepreneurs such as Mr. Jones to consider the local community or the environment in corporate decisions, rather than just their shareholders.Opponents of benefit-corporation laws say they’re unnecessary because investors can already spend their earnings on good causes, and they will have more of those earnings if the company sticks to maximizing profits. Others worry that the laws strip away corporate accountability to investors. “It’s politically correct to suggest that a company benefit the public rather than its investors. But investors are the public,” says Charles Elson, who teaches corporate governance at the University of Delaware.

Under the new laws, entrepreneurs can set out their social and environmental objectives in corporate charters and bylaws. More than 200 for-profit businesses, from small brewers to outdoor-clothing maker Patagonia Inc., have converted their corporate structures to benefit corporations in recent years.

Frank Carpenito, the 50-year-old president of Dancing Deer Baking Co. in Boston, says he converted his firm last year, paying about $30, plus legal fees. He hopes the move will protect the bakery’s support for local causes, including over $300,000 in scholarships to homeless mothers during the past decade.

Mike Hannigan, the president of an office-supply service in Oakland, Calif., converted to a benefit corporation last year under a new California law. He wants his 20-year-old firm, Give Something Back, to continue to contribute to local food banks and homeless shelters, among other causes.

But as social entrepreneurship gains momentum across the U.S., supporters of state benefit-corporation laws are clashing over how strictly entrepreneurs should be held to their social and environmental missions. One big concern is that businesses might adopt the term “benefit corporation” for marketing purposes without taking meaningful steps to address social and environmental concerns.

Opponents of tougher requirements say smaller companies need the flexibility to pursue good causes when doing so won’t hurt their business. For example, under stricter rules a benefit corporation that commits to donating 25% of its annual earnings to local charities would be legally bound to do so, even if it became unprofitable.

The dispute is playing out in Colorado, Mr. Jones’s home state, where lawmakers are expected to vote on whether to recognize benefit corporations by month’s end. The House has already approved a bill, which is now before the Senate.

Critics say the legislation is too watered down because it fails to require entrepreneurs to consider the social and environmental impact of every business decision they make. They also worry the Colorado proposal doesn’t require a benefit corporation to have an independent board member who holds it to its goals. Similar laws in Massachusetts and some other states include these requirements.

The critics fear the Colorado bill could set a bad precedent that other states will follow. Lawmakers in at least 20 more states, including Texas, Florida, Arizona, and Delaware, are expected to take up benefit-corporation laws this year. “This just muddies the waters and will lower the standards across the board,” says Kyle Westaway, a New York-based lawyer who represents social entrepreneurs.

Rep. Pete Lee, a Democrat from Colorado Springs who introduced the bill in January, says businesses that choose to become benefit corporations should be allowed to “promote the public good” through one-off projects, such as a fundraising drive for a local school or a day off for employees to do charitable work, that don’t hurt profits. “I don’t think it should be too prescriptive,” says Mr. Lee of the legislation, which was led by the state bar association.

Mr. Jones, a former civil engineer at Halliburton Co., HAL +3.27% the oil-field giant, hopes Colorado will adopt strict laws. That way, he says, both investors and consumers will be able to tell the difference between companies that are doing good and those that just do good public relations.

In December, Namaste, which shares ownership with about half of its 100 employees, launched a private offering to raise $1.5 million in order to expand outside the state. It expects to raise $750,000 by the end of this month. “Investors are looking for more companies like ours,” Mr. Jones says.