Europe’s Unemployment Problems Worsen; Southern Europe’s economic malaise echoes Great Depression

April 26, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated April 25, 2013, 3:25 p.m. ET

Europe’s Unemployment Problems Worsen

Spain and France Both Record New Highs, Adding to Pressure to Ease Up on Austerity in Favor of Economic Stimulus

By ART PATNAUDE in Madrid and WILLIAM HOROBIN in Paris

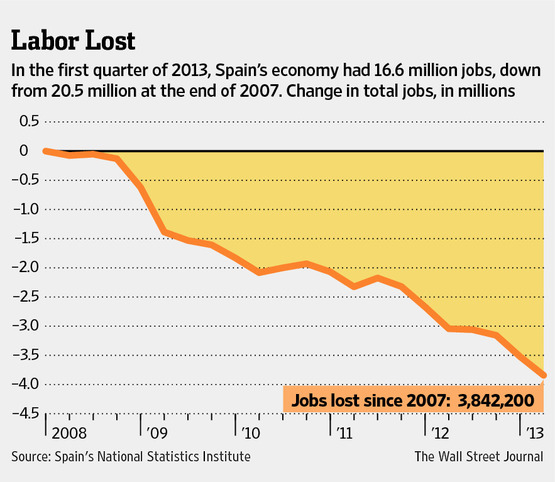

As unemployment rises to 27.2% of the workforce, the Spanish government is about to introduce a budget that eases austerity measures. Friday’s budget will be another sign that supporters of austerity are losing the political battle in Europe as the social cost becomes too high. Unemployment in Spain and France has jumped to new highs, data showed Thursday, lending ammunition to a growing chorus calling for easing the euro zone’s austerity drive as the cure for its debt crisis because of the high social fallout.

The jobless rate in Spain rose sharply to 27.2% of the workforce in the first quarter, the highest level since records began in the 1970s. In France, the number of registered job seekers who are fully unemployed rose to more than 3.2 million, topping a previous record set in 1997. The weak figures in France and Spain, two of the biggest euro-zone economies, come on the heels of sharp rises in unemployment in March in the Netherlands and Sweden—an indication that the European Union’s northern members are also suffering from the bloc’s economic weakness. The slowdown has prompted a broad rethink of the reliance on austerity measures in the bloc.

Last week, the International Monetary Fund joined the U.S. in saying the euro zone should ease up on belt-tightening, arguing it was holding back the global economic recovery and could end up being self-defeating. The head of the European Commission said Monday thepolicy had “reached its limits.”

In France, President François Hollande has championed the charge for greater emphasis on growth, arguing that more austerity at this point is a risk, not a remedy to Europe’s crisis.

At a news conference in Beijing on Thursday he repeated that call, adding that European countries running trade and other surpluses—a camp that includes Germany, though he didn’t name it—should help others by creating more domestic demand.

“I can’t accept as French president that Europe is seen as a difficulty or a problem,” he said. “Europe shouldn’t be a problem; it should be a solution for global problems and a solution for global growth.”

Mr. Hollande recently abandoned his target of getting France’s budget deficit down to 3% of annual economic output this year and will now be satisfied with 3.7%. Other countries are also pushing back against the austerity mantra.

Portugal this week presented anambitious stimulus program aimed at growth, and the Spanish government is expected to outline a similar shift on Friday.

European Commission Vice President Olli Rehn said Thursday that fiscal belt-tightening is still necessary in the European Union, but there is now leeway to slow the pace of budget cuts.

“The pace of fiscal consolidation is slowing down in Europe,” Mr. Rehn said. He added that there was now “room to make fiscal policy with a more medium-term view.”

But Jörg Asmussen, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s appointee to the European Central Bank’s executive board, spoke out in defense of austerity, calling it the only way for countries to secure long-term stability.

“Delaying fiscal consolidation is no free lunch,” he told a conference in London.

Germany’s labor market has held up well, weathering a wider recession in the euro zone. The unemployment rate is roughly half that of France—and near its lowest level since reunification—after taking into account seasonal fluctuations.

With no economic growth expected this year, Mr. Hollande is pinning his hopes on state-sponsored incentives for employers to make good on his pledge to start bringing unemployment down by the end of the year. He has also overseen an agreement to increase flexibility for employers, which he hopes will encourage them to hire.

Experience from Spain shows there may be no quick fix. Its overhaul of labor laws last year to give companies more hiring flexibility has yet to raise the overall employment numbers.

“Spain lacks the tools to break free from the recessionary spiral and stem the increasing risk that the downturn is evolving depression-like characteristics,” analysts at IHS Global Insight wrote in a note to clients.

Many of those in the jobless ranks—6.2 million of Spain’s 47 million people—say they have little hope of finding work soon.

Elena Soler Pérez, 41, lost her job this past August as a personal assistant for an administrator at Catalonia Polytechnic University in Barcelona. She had worked there for 12 years.

Ms. Soler Pérez, who said her savings will last about another year, has been searching for new jobs through private and government employment agencies, online social networks and traditional ads. She is registered with Spain’s job-finding agency.

“My relationship with the [agency] is one of just showing up for a head count,” she said. “I suspect this is the same for everybody else, too.”

Late Thursday, hundreds of people marched on Spain’s Parliament building to protest the economic crisis and political corruption. Seeking to head off violence, police arrested four people found with fireworks and gasoline and 11 others who had chains and clubs.

Among the protesters was Elias Rubio, 18, who said his mother had lost her job in a copy shop and he wasn’t able to pursue studies to be a mechanic because of cuts to education.

“There is nothing here in Spain—no work, no school, only incompetence and corruption in government,” he said.

Southern Europe’s economic malaise echoes Great Depression

Today’s northern European countries are running up record current-account surpluses, just as some southern European countries are experiencing Weimar-level unemployment

Federico Fubini

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 23 April 2013 10.46 BST

Charles P Kindleberger, the great economic historian, once noted that the Great Depression was so deep and so long because of “British inability and American unwillingness” to stabilise the system. Among the functions that the great powers failed to perform, a few should ring a bell to European leaders today. Kindleberger singled out their failure to “maintain a market for distress goods” – that is, to keep their domestic markets open to imports from crisis-stricken economies.

Surely history is not repeating itself – at least not in the literal sense. European creditor countries today are not tempted by anything like America’s Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which crippled world trade in 1930.Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland remain committed to theEuropean Union

‘s single market for goods and services (though their national regulators hinder intra-European capital flows).

Still, one cannot help but notice similarities with the 1930s. At the time of the Great Crash, the United States and France were piling up gold as fast as the Weimar Republic was piling up unemployment. Today’s northern European countries are running up record current-account surpluses, just as some southern European countries are experiencing Weimar-level unemployment. For Italy, Europe’s fourth-largest economy, the current slump is proving to be deeper than the one 80 years ago. Meanwhile, huge savings and potential demand for consumer and capital goods remain locked up next door.

How did this happen? As Kemal Derviş has pointed out, the cumulated current-account surplus of the Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany is now around $500bn (£327bn). This dwarfs China’s surplus at its mercantilist peak of the mid-2000’s, when the G7 (including Germany) regularly scolded the Chinese for fuelling global imbalances.

More striking still, in the now-rebalancing eurozone, many countries’ current accounts are trending toward balance (and Ireland has recently moved from deficit to a small surplus). One exception is Germany, whose external position strengthened over the last year, with the surplus rising from 6.2% to 7% of GDP – all the more remarkable in the context of a European recession and a slowing domestic economy.

Indeed, Germany’s GDP grew by just 0.9% last year, and is forecast to slow further this year, to 0.6%. Slackening growth, declining private and public debt, and super-low interest rates would suggest loosening up a bit and supporting aggregate demand. Instead, a distorted view of what competitiveness really is (mis)leads politicians to consider large external surpluses an unqualified good and a testament to virtue, whatever the consequences abroad.

The second exception is France. Over the last year, France’s external deficit deteriorated further, from a 2.4% to 3.5% of GDP. France now faces zero or negative growth in 2013, and seems to have reached the point at which it must reverse course on competitiveness or risk more trouble ahead.

Unfortunately, this, too, is reminiscent of the 1930s. To paraphrase Kindleberger, French inability and German unwillingness to stabilise the system are contributing to an ever more intractable European crisis.

In this respect, the debate in Brussels concerning the “right” amount of austerity misses the mark; in the same vein, southern European leaders’ strategy of blaming German chancellor Angela Merkel for their own tax increases looks increasingly futile. It is not Germany’s fault that Italy and Spain had to tighten their budgets last year. As research by Ray Dalio shows, any country with an average cost of debt far above its nominal GDP growth has little choice but to resort to belt-tightening.

For example, in November 2011, interest rates on Italian sovereign bonds were around 8% all along the curve, even as the government faced refinancing needs totalling nearly 30% of GDP over the following year. Because debt monetisation was not an option, austerity had to ensue at that point, regardless of what Merkel – or anyone else – had to say.

This suggests a collective failure by European leaders to frame the response to the crisis properly. Southern European leaders have wasted time and energy asking Merkel for weaker fiscal medicine. Merkel and her allies have invested just as much political capital in resisting such pressure. And the European Council has become a theatre for tired repetition of the same old show, performed mostly for domestic audiences, with little attention devoted to the opportunity – once Italy’s political stalemate has ended and Germany’s upcoming election is over – to re-write the script.

Southern countries, still largely in denial, should accept the need for deeper, competiveness-enhancing reforms. Germany and its allies, for their part, should accept that running high external surpluses is damaging the eurozone and themselves, and that it is time for them to put part of their huge excess savings to work to support growth. The failure of leaders in France, Italy, and Spain to raise this issue more effectively has been a clear shortcoming so far.

Without a pro-growth, pro-reform deal, southern Europe’s attempts at deleveraging may result in a politically destabilising depression. As Mark Twain observed, “History doesn’t repeat itself. At best, it sometimes rhymes.” In Europe’s case, the poetry could be very dark.