Regulators fret about the risk of a sudden rise in long-term bond yields

May 4, 2013 Leave a comment

Regulators fret about the risk of a sudden rise in long-term bond yields

May 4th 2013 | Washington, DC |From the print edition

THE Federal Reserve has long acknowledged trade-offs in its efforts to revive growth with ultra-easy monetary policy. Now those trade-offs are getting starker. On April 26th America’s economy was reported to have grown by 2.5% on an annualised rate in the first quarter: stupendous by European standards, but less than expected. On April 29th underlying inflation slipped to just 1.1%. On May 1st the Fed duly said it would keep rates near zero, as it has since 2008, and keep buying $85 billion of government bonds a month, although it may vary the pace depending on the outlook for inflation and jobs.

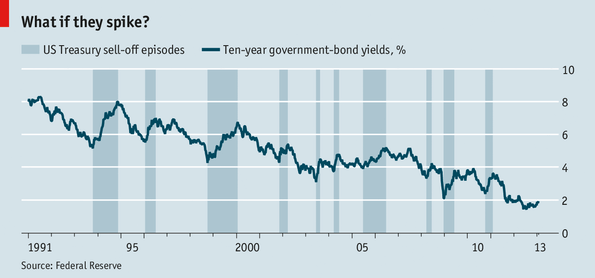

A prolonged period of low rates carries the risk of asset bubbles. In its annual report issued on April 25th America’s new Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), a watchdog that includes the Fed, warned that a “sudden spike in yields and volatilities could trigger a disorderly adjustment, and potentially create outsized risks.” For its part, the IMF noted in its latest “Global Financial Stability Report” that “credit markets…are maturing more quickly than in typical cycles.”The FSOC and the IMF worry in particular about unusually low yields on long-term bonds (see chart). Suppose an investor expects short-term rates to average 2% for the next ten years. A ten-year bond need only yield 2% to provide the same expected return. But investors in long-term instruments usually demand a few percentage points more, a difference called the “term premium”, to compensate for the possibility the world turns out differently. The term premium is now around zero, according to the FSOC.

Several factors are involved. The Fed has been unusually explicit in committing to keep interest rates near zero until unemployment falls to 6.5% or lower, which analysts take to mean until 2015. The Fed’s purchases have squeezed the supply of risk-free government debt, forcing investors with a particular need for such paper, such as life insurers, to accept much lower yields. Finally, the hunger for safe assets may have elevated demand for Treasuries.

That is potentially worrying. Changes in expected short-term rates account for most bond-market sell-offs. In 1994 rapid Fed tightening led to a bloodbath in bond markets. In theory the Fed could promise to change rates gradually and with lots of notice. But even without a change in monetary policy, a lurch in investors’ risk appetite may jolt the term premium upwards.

How damaging that would be depends on how reliant investors are on debt or short-term financing, which would make them more likely to sell into a falling market. Banks have much thicker capital buffers than they did. Insurers and pension funds have expanded their exposure to long-term bonds, but they also have long-term liabilities. However, real-estate investment trusts (REITs) that buy mortgage-backed securities with short-term repo loans have mushroomed. And borrower behaviour attests to a broader reach for yield. Rwanda issued its first Eurobond in April, a ten-year $400m issue that was more than eight times oversubscribed. On April 30th Apple issued the largest-ever investment-grade bond, a $17 billion hunk of debt that was three times oversubscribed.

The tricky question is what to do about such risks. Insurance regulators now require insurance companies to prepare for a broader range of interest-rate scenarios. The Fed three years ago reminded banks to measure and monitor interest-rate risk. Then again, holding down long-term interest rates and encouraging investors to take more risk is the whole point of the Fed’s policy; if successful, it will revive demand and economic growth. That this also raises risks to the financial system is a trade-off the Fed seems prepared to live with.