Why Myanmar’s military rulers are giving power to the people; Why investors still need to proceed with caution

May 28, 2013 Leave a comment

Why Myanmar’s military rulers are giving power to the people

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

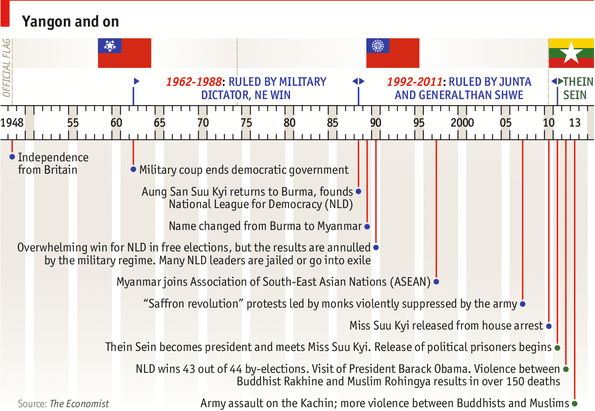

MYANMAR’S TRANSITION HAS been a top-down affair. This, more than anything, distinguishes it from other recent upheavals such as the “people power” revolutions of the Arab spring, the fall of communism in Europe and the toppling of Indonesia’s President Suharto. At crucial moments the threat of mass protests hurried the process along. Government advisers concede that in 2011 they were afraid of an Arab spring on the streets of Yangon. The army had mercilessly oppressed protests such as the aborted “saffron revolution” in 2007, led by monks, and the pro-democracy uprising in 1988 that had first propelled Miss Suu Kyi to national prominence. Those 1988 protests led to elections in 1990 which were won by the NLD but annulled by the government. For the main part, though, Myanmar now stands as a rare example of an authoritarian regime changing itself from within.By the start of the 2000s it had become clear that a couple of decades of Ne Win’s “Burmese Way to Socialism”, followed by a couple more of Than Shwe’s crony capitalism, had reduced a once prosperous country to penury. In 2003 the government outlined its “seven-step road map to democracy”. A national convention was held to draft a new constitution, duly approved in a referendum in 2008. The elections it provided for took place in 2010 and by all accounts were rigged. The new president who was installed in March 2011, Thein Sein, had been hand-picked by his predecessor, Than Shwe, probably the most pitiless of Myanmar’s military strongmen. Léon de Riedmatten, a Swiss citizen who worked in Myanmar for several international organisations throughout the 2000s, says there “was nothing very surprising, it all went to plan. There is no doubt that Than Shwe is the architect of the existing democracy.”

However, the sort of democracy that Than Shwe and his satraps had in mind was rather different from what Westerners might understand by the term. The military rulers called their version “disciplined democracy”—a version in which the army would retain a lot of power whatever happened in any elections. The idea was to offer just enough of a say to the people to win support from the army’s opponents at home and abroad for rebuilding the country’s shattered economy.

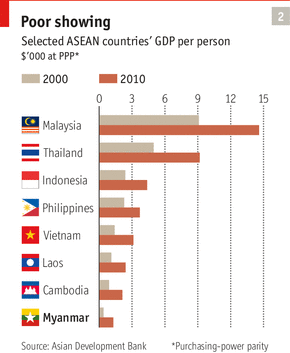

Thein Sein, to his great credit, realised that strictly rationed freedom would not persuade America and Europe to lift sanctions, nor would it gain Miss Suu Kyi’s support; so once in power he pushed the democratic reforms much further than Than Shwe had envisaged. The need was urgent. Back in 1962 Myanmar, with its abundance of minerals, teak, rice, oil and gas, had been one of the wealthiest countries in the region, with an income per head of about $670, more than three times Indonesia’s and twice Thailand’s. By 2010 the IMF estimated that Myanmar had the lowest GDP per person in South-East Asia (see chart 2).

The country had achieved a great leap backward just as the rest of Asia was enjoying record growth. The contrast between Myanmar and its neighbours had become too great to obfuscate either at home or abroad. Thein Sein eventually acknowledged publicly that “there are still too many people whose life is a battle against poverty, a hand-to-mouth existence.”

But in order to rebuild its economy, the country needed an end to Western sanctions. It had become dangerously dependent on resource-hungry China, which had stepped into the breach as the West shunned Myanmar. Chinese companies built dams, roads and pipelines there, often for the sole benefit of consumers back home.

Having long enjoyed a free hand, China was shocked when in September 2011 Thein Sein suddenly called a halt to its biggest construction project, the $3.6 billion Myitsone dam in Kachin state. The 68-year-old president, slightly stooping and studiously uncharismatic, may seem an unlikely free-thinker, but his decision on the Myitsone dam marked him out as quite different from his predecessor, Than Shwe (who now keeps a low profile and is rarely seen in public). Thein Sein wanted to end the country’s over-dependence on China, and he had begun to listen to the Kachin, who were vehemently opposed to the dam.

Zhu Feng, a professor of international studies at Peking University, says the change of mind over Myitsone “set alarm bells ringing” in China’s government. Myanmar was turning awkward, and it was America that stood to gain most from China’s discomfort as a then fairly new American government appeared more willing to re-engage with the rogue state.

We unclench, you unclench

Previous American administrations had branded Myanmar a danger to world peace. But when Barack Obama became president, he promised to “unclench” America’s fist if the world’s most recalcitrant regimes did the same—a strategy that got nowhere with Iran and North Korea but worked wonders with Myanmar. Soon after the Obama administration was installed in early 2009 it ordered a review of America’s policy towards Myanmar. It attempted some cautious re-engagement, retaining the sanctions but opening up a dialogue. At first this did not seem to do any good. But from the moment that Thein Sein took over, says Derek Mitchell, now America’s ambassador to Myanmar, “we noted that this guy was different,” that he was someone the Americans could speak to.

Since then a succession of American envoys has promised to ease sanctions and reduce the country’s isolation in exchange for political reform, notably the release of political prisoners. Thein Sein did everything that was asked of him. In November last year he received the ultimate endorsement of his country’s reform efforts when Mr Obama visited Yangon.

Some argue that the West’s re-engagement with the former pariah state has been too hasty. Perhaps so, but it has also given enormous leverage to Miss Suu Kyi, the opposition leader, since the Americans never moved a step before obtaining her approval. In August 2011 Thein Sein invited her to the presidential palace in the capital, Naypyidaw, knowing that he would need her approval if the Americans were to support his reforms. That is how it turned out.

At a time when America is generally turning towards Asia, the re-engagement with Myanmar has been the most striking external aspect of the country’s transition. Hawks in Beijing see this as more evidence of America’s aggressive attempts to contain China’s rise. Enlisting Myanmar even partly in the Western camp has certainly been a coup for Mr Obama, but it does not automatically lead to a new “great game” in Myanmar between the two rivals. Mr Mitchell argues that “there is a competition [in Asia] in terms of values and rules, but it’s not necessarily anti-China.”

Can old soldiers just fade away?

The economic, domestic and strategic explanations for Myanmar’s transition all suggest that it can become a normal democratic country, but much will depend on the army. Over the decades this 350,000-strong institution has come to dominate all aspects of life in Myanmar. If there is to be real change, the army must not only stop fighting the Kachin and other ethnic groups, it must release its stranglehold on parliament and on the economy.

This is where the limitations of the top-down process become obvious. The constitution of 2008 was drafted by the army and gave it a wholly undemocratic lock on power to ensure that it retained control of the transition. Most egregiously, the army awarded itself an unelected block of a quarter of all seats in the new national and state parliaments so the constitution could not be changed without its consent. It also assumed sovereign powers over its own affairs as well as a big say in some of the civilian ministries. All the current ministers, including Thein Sein, are former army officers.

In its modern incarnation, the army was formed by Aung San, Miss Suu Kyi’s father and the man who led Myanmar to independence from Britain. It regards itself as the only institution that can hold fissile Myanmar together in a “union”, as the country is officially called. This would suggest that the army will halt any moves towards a more federal organisation and more democracy, both of which would involve devolving power to the ethnic Karen, Kachin and others, and, to the military mind, the dissolution of “the union”. Such changes would also reduce the army’s importance, and thus its budget.

It is also widely thought that the army and its proxy party in parliament, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), have a vested interest in resisting further economic liberalisation because that would undermine the business monopolies enjoyed by former army officers. In particular, two vast military holding companies, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (UMEHL) and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), have tentacles everywhere, from hotels to airlines, from chicken farms to jade mines.

At every turn people have braced themselves for a backlash from army hardliners with the biggest institutional and economic stakes in the status quo, but it hasn’t come, at least not yet. Moreover, when reforms are debated in parliament and in the executive, the hardliners have tended to lose arguments, and votes. Richard Horsey, a consultant who is an old Myanmar hand, says that so far the army has accepted the changes like everybody else. It has not resisted the demand for the UMEHL and the MEC to pay taxes, for instance, and the two holding companies have lost their monopolies on lucrative imports of cars, edible oils, cigarettes and beer. “These are massive changes,” says Mr Horsey.

Even bigger changes could come out of a review of the constitution, considered unthinkable even a year ago but now proposed by the USDP itself. That could shake up the very foundations of the army’s political power—and might even allow Aung San Suu Kyi to become president.

Why investors still need to proceed with caution

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

MANY OUTSIDERS SEE Myanmar’s opening up as an unmissable economic opportunity. It is the last large Asian country to become connected to the world economy, leaving only North Korea, which is both smaller and infinitely less promising. Myanmar, with about 60m people, is closer to Thailand (70m) or Vietnam (88m). Indeed, its rapid development recalls Vietnam’s opening up, the doi moi, in the late 1980s, after decades of war and isolation.

The opportunities for foreign investors are plain. As well as offering a large potential domestic consumer market, Myanmar is rich in gas, oil and minerals. It has about 50m barrels of proven oil reserves and 280 billion cubic metres of gas. China is only one of many contenders for exploiting this wealth. On April 11th Myanmar’s government opened an auction of 30 blocks of offshore oil and gas. Big international oil companies such as Chevron, Total and Royal Dutch Shell will be interested, as will the Thai, Malaysian, South Korean and other Asian companies that stuck with Myanmar during sanctions. The government is putting a further 18 onshore blocks up for bids.

Myanmar has oil and gas in abundance, but investors are equally interested in what it does not have, which is pretty well everything else. After decades of state control and economic isolation, Myanmar is almost devoid of any functioning financial services; one bank estimates that only about 10% of the population have any sort of bank account. Spotting the opportunity, 28 foreign banks have set up representative offices in the country. Under existing legislation all they are allowed to do is conduct research, but the potential for full retail banking is clear. Microfinance companies are already permitted to operate. Cambodia’s very successful ACLEDA bank, which has a strong presence in microfinance throughout the region, has just opened in Myanmar and should do well.

The telecoms sector was heavily restricted by the old military regime, mainly for political reasons, but now the government is auctioning off the nationwide network to a mix of local and international firms. This auction attracted as many as 91 initial bids, with the world’s biggest firms all putting their hat in the ring. Twelve companies have been shortlisted.

Tourism is another industry desperately in need of investment. Tourist numbers have risen to about 1m a year, causing hotel prices to rocket. But supply is now beginning to catch up. Accor, a French hotel group, recently announced that it was building big new hotels in Yangon and Mandalay, as well as the first ever international hotel in Naypyidaw. With its natural beauty and its wealth of Buddhist monuments and pagodas (notably in the ancient city of Bagan, to many the equal of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat), Myanmar might eventually see as many visitors as Thailand, which is currently getting about 21m a year. That would significantly boost its economy and provide hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

Thein Sein’s government is trying hard to get the right regulatory framework in place to absorb the wall of money heading Myanmar’s way. So far the legions of foreign consultants and lawyers now swarming all over the country have been impressed by the results. Most importantly, the government is fully aware that after decades in seclusion it has a lot to learn. Ministers and officials are soaking up all the advice they can get, wherever they can find it.

Help wanted

In the very early days, this meant ordering in episodes of “The West Wing”, a television series about the White House, to see how democracy works in practice. Now the learning process has become more targeted. The Japanese are helping to draft a stockmarket law; the Asian Development Bank is working on a new company law; the IMF, among others, is helping to reform the central bank; and the British have flown Shwe Mann, the Speaker of the lower house of parliament, to London to see democracy in action at Westminster.

Even the Japanese, keener than most, are being ultra-cautious. The generals jokingly tell their guests from Japan that their home country has joined NATO—“No Action, Talking Only”

The reforming ministries have already passed or drafted many of the laws needed to tilt the economy towards openness and liberalism, probably to the point of irreversibility. Early successes included the swift abandonment of the old official exchange rate of the kyat in favour of a managed exchange rate close to the old unofficial level, which gives the buyer about 100 times as many kyat for his dollars. A new law to legalise trade unions in the private sector was passed in 2011. And a new investment law took effect towards the end of last year, giving investors most of what they wanted. More recently the government also pledged to sign up to the New York Arbitration Convention. Simon Makinson, managing partner in Myanmar of Allen and Overy, a law firm, says this is a good thing because no big multinational company would have wanted to see its commercial disputes settled under Myanmar’s own archaic legal system. The finance industry has been cheered by a proposal currently being debated in parliament that the central bank be split off from the government and manage monetary policy on its own.

But much more remains to be done. Thousands of businessmen now fly to Naypyidaw on the new air-shuttle service from Yangon to be flattered by ministers, quiz officials and look at opportunities, but so far relatively few are biting. Even the Japanese, keener than most, are being ultra-cautious. The generals jokingly tell their guests from Japan that their home country has joined NATO: “No Action, Talking Only”.

The Japanese are right to be prudent. Myanmar may have a lot of potential, but it remains a “frontier” investment destination. The obvious drawbacks, as the manager of Japan’s Famoso factory has learned, include an intermittent electricity supply; internet connections that are poor in the cities and almost non-existent outside them; dreadful roads that often become impassable in the monsoon season; and scarce and extremely pricey office space.

Most of these physical problems can probably be fixed relatively quickly. Myriad other shortcomings will take much longer to remedy. The country’s once excellent education system was all but destroyed by the generals, leaving generations of Burmese with poor language and numerical skills and no higher education worth the name. Labour might be cheap, but all those new employers will soon run into severe skills shortages. Qualified professionals of almost all kinds, from lawyers to doctors to teachers, are in short supply.

Beneath a thin veneer of expertise and dedication at the very top, much of the bureaucracy consists of former military officers who have been provided with sinecures. They constitute what is known as the “green ceiling”, which means that getting anything done can take a long time. According to Romain Caillaud, a Yangon-based consultant for Hans Vriens & Partners, a consultancy, “there are still very few multinationals making money in Myanmar…tenders require a lot of work to be completed, it takes a lot of effort and makes the process unprofitable.” Corruption is a big problem, with many of the quasi-military bureaucrats expecting bribes and kickbacks. And although most sanctions have been lifted, those that remain in place will force many (particularly foreign banks) to tread warily for a while yet. America, for instance, maintains restrictions on dealing with the 100 or so most prominent “cronies” of the old military regime.

But the most important legacy of Myanmar’s recent past is the unresolved ethnic strife that has been tearing the country apart for decades. The government knows that investors crave stability and peace more than anything else. Can it move the country towards a more representative, more federal system that would offer the best hope of providing it?

A Burmese spring

After 50 years of brutal military rule, Myanmar’s democratic opening has been swift and startling, says Richard Cockett. Now the country needs to move fast to heal its ethnic divisions

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

A WALK AROUND battered, ramshackle Yangon, Myanmar’s biggest city and former capital, quickly makes it clear how far the country has fallen behind the rest of Asia over the past half-century. In large part the place is but a ghostly reminder of former glories. Under British colonial rule, before independence in 1948, Rangoon (as it was then) was a thriving, cosmopolitan entrepot, the capital of Burma, one of the region’s wealthiest countries. All that came to an abrupt end in 1962 after a junta of army officers, led by the brutal General Ne Win, seized power and launched the country on the quasi-Marxist “Burmese Way to Socialism”. Private foreign-owned businesses were nationalised, prompting the exodus of hundreds of thousands of people, many of Indian origin. The country’s tenuous attachment to democracy was broken. Myanmar, as Burma was later renamed by its ruling generals, retreated into itself. Comprehensive Western sanctions hit home from the mid-1990s onwards, only slightly alleviated by an injection of Asian money.

Yangon, with its old cars and bookshops selling textbooks from the 1950s, attests to this seclusion. The colonial-era banks, law courts and department stores, once as imposing as any in Kolkata or Shanghai, have all but crumbled away. Except for the magnificent Shwedagon Pagoda, lovingly regilded to welcome the crowds of pilgrims and tourists, most of the city seems to have remained untouched for decades. Even youthful rebellion is stuck in a time-warp. Boys are still gamely attempting to flout authority by dressing up as punk-rockers.

But now the country has seen another about-turn, almost as abrupt as that in 1962. Over the past two years dramatic reforms introduced by a new president, Thein Sein, prompted by the country’s increasingly desperate economic straits, have started a rapid transition from secretive isolation to an open democracy of sorts. The mere fact of such a change taking place has surprised the world; its speed and breadth have caused widespread bewilderment.

Even in careworn Yangon the signs are everywhere. The pavements are cluttered with traders selling an array of newspapers, newly licensed and privately owned, carrying pictures of Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD). Less than two years ago the image of the defiant Nobel peace-prize laureate was banned; under a strict censorship system her name could not even be mentioned in the press. Now all censorship before publication has been lifted; any paper, such as the NLD’s own newspaper D Wave, can apply to publish daily; and Miss Suu Kyi’s photo festoons T-shirts, mugs and biros for sale on almost every street corner. People are still excited about being able to speak freely, even about politics, without constantly having to look over their shoulders. Some of those interviewed for this special report had never before talked to a foreigner, let alone a foreign journalist.

With greater political freedom has come economic change. Almost all Western sanctions against the country have been lifted, and the country is swiftly reconnecting with the international financial system. Visitors no longer have to wander around with so many wads of dirty old kyat, the local currency, in their pockets: the first international ATM in Yangon has recently started disgorging fresh banknotes. Some outlets are now accepting credit cards. Real Western brands, rather than pirated versions, are about to appear in a few shops. An influx of relatively wealthy foreigners and returned natives will need new offices and apartments. Prime parts of Yangon are rapidly being flattened to cater for the expected demand.

Myanmar’s transformation is the most significant event to have taken place in South-East Asia in the past decade, and this special report will argue that it will have important consequences for the rest of Asia as well. In the space of just a few years almost every aspect of life has been touched by the reform programme. Not only was Miss Suu Kyi released from house arrest in November 2010, but the vast majority of the country’s thousands of political prisoners have been freed. The NLD, harassed for decades and then declared illegal for refusing to participate in rigged elections in 2010, is legitimate once more. In April 2012 it won 43 out of 44 seats it contested in by-elections, the country’s first free and fair polls since the 1950s: its MPs, led by Miss Suu Kyi, now sit in parliament.

The blacklists barring former political opponents of the regime and “hostile” journalists have been put away. A new labour law covering private industry has encouraged the formation of new trade unions. Once a byword for bleak authoritarianism, Myanmar is now doing better than some of its Asian peers on civil and political rights.

International financial institutions such as the World Bank have returned, often after writing off the country’s old debts. Thein Sein now tours the world’s capitals much like any other leader, even if he does not get the rapturous welcome given to Miss Suu Kyi wherever she goes. And this December Myanmar celebrates its return to regional respectability by hosting the South-East Asian Games for the first time since the 1960s.

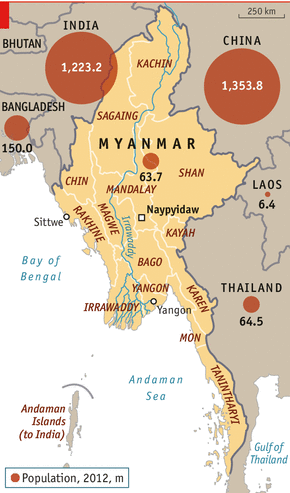

Foreign governments and multinationals have converged on a country that occupies a unique geostrategic position between the new Asian superpowers of India to the west and China to the east. Private companies are jostling to capture a share of an almost virginal consumer market of some 60m people. This special report will weigh the pros and cons of rushing into what investors are calling “the final frontier”.

Don’t cheer too soon

The new sense of optimism and confidence among Myanmar’s own people is still tinged with caution. Hopes in the past have been raised by modest doses of liberalisation, only to be dashed again. It is also clear that in easing military control, Myanmar’s reformers have provided an opening for dark forces that authoritarian rule had kept in check. Since June 2012, starting in the city of Sittwe in western Rakhine state, Buddhist mobs have killed hundreds of Muslims and razed their mosques and homes to the ground. It was not what the reformers had intended, but the effects of relaxing restrictions can be unpredictable.

The first two months of 2013 also saw the heaviest fighting yet between the Myanmar army and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), an armed militia of the Kachin people. Like many of the other ethnic minorities that make up about 40% of Myanmar’s population, the Kachin, in the far north of the country, have been battling for decades for autonomy and against majority Burman rule. For all the past two years’ economic and political progress in the Burman heartlands in the centre of the country, much of the periphery remains largely cut off and in a state of, at best, suspended hostilities.

Thein Sein’s government has signed ceasefire agreements with most of the armed groups, but a lasting political solution still seems a long way off. It will require proper citizens’ rights to be granted to the country’s entire population, including marginalised people like the Rohingya Muslims, which all of Myanmar’s rulers since independence have neglected to do. This special report will argue that the current period of upheaval is the best possible opportunity to resolve these ethnic disputes.

The opening up of Myanmar could transform the rest of Asia

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

ON THE NORTHERN outskirts of Yangon lie the sprawling industrial estates that used to provide Myanmar’s economic muscle, such as it was. Now, after decades of sanctions and economic mismanagement, many of the factories have been demolished and the ones left standing are mostly derelict. But amid the rubble are signs of new life, not only for Myanmar but for the rest of Asia. Near the gates of the Mingaladon Industrial Park two new Japanese-owned factories have sprung up out of the debris. One of them, Famoso Clothing, offers a glimpse of a better future for Myanmar—and for Asia.

Owned by Daiei Ready Made Clothes Corporation, based in Japan’s Nagoya, Famoso was set up in Yangon in 2002 as a small operation to make men’s suits exclusively for the Japanese market. The parent company did most of its business in China, where it employed thousands of local workers in three factories. But three years ago two of the factories in China were closed and the plant in Yangon was rebuilt at a cost of $7m to become the company’s new Asia hub, explains Famoso’s managing director, Kazuto Yamazaki. The company’s last Chinese factory will close within a year and the Yangon operation will triple its output, from 170,000 suits a year to half a million.

The reason for the switch is simple, says Mr Kazuto: the high cost of labour in present-day China. In Myanmar he pays workers around $100 a month, a quarter of the going rate in China. Moreover, Famoso is well placed to take advantage of the most important economic consequence of Myanmar’s political reforms: the ending of Western sanctions, and in particular the ban on imports from Myanmar. Famoso is making its first suits for Britain’s Marks & Spencer, ready for shipping in July. Famoso has even applied for a licence to sell its suits in Myanmar itself for the first time. Mr Kazuto says there is growing demand for Western clothes from politicians in Naypyidaw.

Famoso has the full backing of the Japanese government. The new prime minister, Shinzo Abe, has identified South-East Asia, and in particular Myanmar, as places where goods can be assembled cheaply but also as new markets to help revive the Japanese economy. Japan has written off billions of dollars-worth of Myanmar’s debts to it and is now investing heavily in the country. Among other things it is building a large new river port, part of the Thilawa Special Economic Zone just south of Yangon, to replace the former capital’s old, silted-up facility. This will cost about ¥20 billion ($200m) in the first instance, which will come out of its overseas aid budget. And if that sounds very Chinese, Japan is spending another ¥14 billion to help fix the dodgy electricity supply in Yangon and a further ¥20 billion on other infrastructure projects throughout the country. The mix of low wages, a plentiful supply of labour and access to American and European markets should mean that many more Famosos will be set up in Myanmar.

Japan’s move to take swift advantage of a reforming Myanmar does not come as a surprise. Its relations with the country had been much better than Europe’s and America’s, though it had maintained some sanctions. Other Asian countries had simply continued to invest there and are now reaping the benefits. Up and down littoral Myanmar all of Asia’s big economies are opening up new trade routes to reach neglected parts of the Asian land mass. The results could transform large swathes of the continent. Myanmar’s geographical position, hugging the Bay of Bengal between the two Asian superpowers, India and China, has become its prime asset.

Geography is destiny

Thailand, for instance, the second biggest investor in Myanmar after China, is forging ahead with a bigger version of Thilawa at Dawei, on Myanmar’s Tenasserim coast. The deep-water port, associated industrial zone and roads connecting them with Bangkok 300km away will cost about $8.5 billion. Thai rulers had for centuries been toying with the idea of building a canal across the Kra Isthmus, linking the Gulf of Thailand directly to the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean to avoid the journey round peninsular Malaysia through the Strait of Malacca (see map). Dawei will at last give Thailand that link.

Grand plans to improve roads all the way from Bangkok to Cambodia and Vietnam are also in hand to spare those countries the tedious rounding of Malaysia and allow them to ship their goods from Dawei directly to Europe. This could profoundly alter the economic geography of South-East Asia, much reducing the importance of Singapore’s and Malaysia’s container terminals as trans-shipment points. Thilawa will also provide companies like Famoso with more direct access to European markets.

To the west, the Indian government also has big plans that will advance its long-standing “look east” policy. It is well into a $100m upgrade of the old port at Sittwe, at the mouth of the Kaladan river in Rakhine state. Big container ships will dock here and offload their cargoes onto smaller barges which will then travel 225km up the Kaladan before transferring onto trucks and into India. The Indians hope that this project will help open up the seven states of their landlocked north-east that are home to about 40m people. They are among the poorest regions in India, partly because of restricted access to the main body of the country through the narrow corridor between Bangladesh and Bhutan known as “the chicken’s neck”. The improvements will make it much easier to ship goods on the new Kaladan route from Kolkata to Mizoram than it was to travel overland through India around the top of Bangladesh.

The Indian government is also working on the road link through Manipur to Myanmar, opening up new overland connections to China and Thailand. The Thai part of this is an ambitious project called the “Trilateral Highway”, which will take traffic from Imphal down to Thailand’s Mae Sot border crossing and to Dawei. The Indians are planning to upgrade the present old and inadequate customs post on Manipur’s border with Myanmar, Moreh, to a new “Gateway to South-East Asia”. The Indians themselves have already rebuilt 148km of road inside Myanmar as part of this project and are set to do more. D.S. Poonia, chief secretary to the state government of Manipur in parched, dirt-poor Imphal, looks forward to the investment and jobs that might flow along these new commercial arteries. Neighbouring Bangladesh is also eyeing up the possibilities of Sittwe’s port. Its consul in Sittwe, Mahbubur Rahman, says Bangladeshi companies want to take advantage of cheap labour and land to set up textile and pharmaceutical factories.

China, long the biggest investor in Myanmar, has been toiling away at its own grands projets. The most important of these are the new oil and gas pipelines that crisscross the country, starting from a new terminus at Kyaukphyu, just below Sittwe, up to Mandalay and on to the Chinese border town of Ruili and then Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province (see map above). This will save China having to funnel oil from Africa and the Middle East through the bottleneck around Singapore.

The Chinese have also been using Myanmar to open up their own Yunnan province. The booming border town of Ruili has become a mecca for Chinese buyers of Myanmar jade, considered to be the best in the world (and highly auspicious). Thousands of shops sell the luminescent deep green gemstone, fashioned into lucky charms and jewellery of all sizes and shapes. Most of the jade mines in Kachin state are owned by the Burmese generals and their crony companies, who sell large quantities of the stone to the Chinese. The badly paid Kachin workers at the mines feel left out.

China wants to turn Yunnan into the country’s biggest domestic tourist destination and has built a big airport at Kunming. Many Chinese tourists do not want to go to Myanmar because they consider it dangerous and dirty, but they can safely visit a surreal plastic recreation of the country’s principal sights on the Ruili side of the border.

Some worry that so many big powers rushing into a relatively small and underdeveloped country could spell trouble. Think-tankers in Beijing fret about America’s ambitions in Myanmar and the inroads that Japan is making into the country. Strategists in Delhi wonder whether the new Chinese facilities on the Myanmar coast might lead to India’s encirclement. India is already blaming China for arming and sheltering some of the dozens of insurgent groups that have been fighting for decades for autonomy in India’s north-east. These conflicts have contributed to the region’s poverty and marginalisation and might yet frustrate attempts to open it up. General John Mukherjee, a former chief-of-staff to India’s Eastern Command, says openly that the many Indian divisions stationed in the north-east are “devoted primarily to watching China and training for operations against China”.

Let’s be friends

On the ground, however, these worries look overblown. Indeed, many of the projects now taking shape across Myanmar have been gestating for years in rather obscure pan-Asian networks of joint Indian and Chinese provenance. BCIM (short for Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar), for instance, a group set up mainly on China’s initiative in 1999, organises seminars and conferences and has been pushing the idea of an integrated economic zone spanning Yunnan, the Indian north-east, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Now that Myanmar has emerged from its isolation, such ideas no longer look far-fetched. Earlier this year BCIM organised a 3,000km car rally from Kolkata to Kunming, passing through Dhaka, Imphal and Myanmar along the way in an effort to stimulate interest in a new trans-Asian highway.

All told, the opening of Myanmar is just as likely to bring Asia’s great powers together as it is to divide them. Myanmar’s government, for its part, will be glad to co-operate with as many countries as possible in order to spread its risks and end its over-reliance on China.

The F-word

Myanmar’s ethnic conflicts are the main obstacle to continued progress

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

FROM THE MOMENT of its birth in 1948 Myanmar has been riven by civil conflict, mainly between the majority Burmans that occupy the country’s central low-lying plain and the hill peoples on its periphery. Myanmar is an artificial product of colonial rule, its borders drawn largely for the convenience of British administrators. The Kachin, Chin, Shan and many other ethnic groups never wanted to share a country with the Burmans; within the newly independent Myanmar, they agreed to do so only on the basis of the Panglong Agreement between them and General Aung San in 1947. This promised “full autonomy in internal administration for the frontier areas”, envisaged the creation of a separate Kachin state and guaranteed that “citizens of the frontier areas shall enjoy rights and privileges which are regarded as fundamental in democratic countries.”

The Panglong Agreement was meant to be the glue to hold together one of Asia’s most ethnically diverse countries. But the ethnic minorities say that from the moment the majority-Burman government took over in 1948 it began to chip away at the accord. After 1962 Ne Win’s military regime abandoned it altogether, trampling on ethnic and religious minorities. In response the ethnic groups all formed armed wings to fight for greater autonomy or even outright independence. The old military regimes made sporadic attempts to arrange ceasefires with the armed groups, most notably in the 1990s and again in the late 2000s, but none of these ceasefires proved permanent, nor did any of them lead to proper political talks.

The reformers in Thein Sein’s government know that ethnic violence could undermine everything they want to achieve. Continuing civil conflict makes the country an unstable and dangerous place, deterring the international investors that the government needs to help rebuild the economy. Moreover, opium-poppy production has flourished in the areas of ethnic conflict. The army is often in cahoots with the drug-producers, and armed militias recruited to protect the poppy fields make peace even harder to achieve.

The government is trying its best to end the conflicts. It has already done better than its predecessors, having signed 13 ceasefire agreements since the end of 2011. Some of these are merely rehashes of older ones from the 1990s, but negotiators say the new ones are better because they have been formally endorsed. On the government’s side much of the credit for this goes to Aung Min, a former railways minister, who is now leading negotiations with the ethnic groups from within the president’s office. Like Shwe Mann in the parliament, he commands respect even from erstwhile opponents. Ngun Cung Lian, who negotiated a tricky ceasefire agreement with the government on behalf of the Chin, like many others was surprised and impressed by “the openness, honesty and willingness to change” of Aung Min and his team. The European Union and others have funded a new organisation, the Myanmar Peace Centre in Yangon, that is providing Aung Min with a secretariat.

Give peace a chance

However, the intense fighting in Kachin state earlier this year was a reminder of the immense difficulties that lie ahead. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) signed a ceasefire agreement with the government in 1994, but 17 years later it resumed hostilities, having achieved no progress on becoming semi-autonomous or independent. Since 2011 hundreds of people on both sides have died and over 100,000 have become refugees. For the first time Myanmar’s army has been using jet aeroplanes in this sort of action. These tactics have raised doubt over how much control the civilian authority exerts over field commanders on the country’s periphery. Thein Sein called for ceasefires that appeared to be largely ignored on the ground; it was only the intervention of an angry Chinese government, alarmed at the prospect of thousands of refugees pouring over the border, that brought the Myanmar government and the KIA back to the negotiating table.

For the Kachin and other ethnic groups the Panglong Agreement still inspires the search for a federal solution to the country’s ethnic problems, the only path to an inclusive Myanmar that can live peacefully with itself. The army, for its part, has been stubbornly insisting on the unitary nature of the state for decades. The question now is whether Thein Sein’s government is willing to go further, build on the current ceasefires and hold talks on political devolution and wealth-sharing.

The fighting in Kachin state suggests that it is not, but people close to Aung Min insist that they are now nearing full political negotiation with the ceasefire groups and that everything is on the table. They say that he and other ministers have even started talking about federalism, breaking an old taboo in government circles. This reflects a genuine evolution of thinking on the government’s part. Ministers started off believing that the grievances of the Chin, Kachin and others arose from economic underdevelopment and could easily be overcome by more infrastructure spending. Only recently have they understood that to win peace they will have to acknowledge and respect the religious and social differences between themselves and the ethnic groups. Whereas the Burmans are Buddhists, for instance, most of the Kachin are Christians, mainly Baptists.

The reformers, and perhaps even a future president Aung San Suu Kyi after 2015, will have to grapple with other such religious and racial divisions. Just as the Kachin, Karen and others have suffered decades of discrimination at the hands of the Burman state, so too have hundreds of thousands of Muslims. The murderous attacks by Buddhists on Muslims in Rakhine state in June and October last year, which spread to central Myanmar this year, reflect a hatred of non-Burman incomers of a different faith dating back to early colonial times.

If these outbursts of racially and religiously motivated killing are not dealt with they could spiral out of control. An archaic law passed in 1982 denies any form of citizenship to the Muslim Rohingya, the victims in Rakhine state, on the ground that they are not an “indigenous race” like the Kachin, Karen and others. The other ethnic minorities have suffered the same sort of discrimination at the hands of Buddhist Burmans for being Christians as the Rohingya have for being Muslims, but in practice the Rohingyas are in the worst plight because as non-citizens they have no rights at all.

The staff at the Myanmar Peace Centre who are supporting Aung Min in his peacemaking efforts are so dedicated to their work that sometimes they do not even go home to sleep. They reckon that the tumultuous events of the past two years have given them a unique opportunity to change Myanmar for good, and they are determined to make the most of it. They have a point. This special report has argued that the country’s military rulers seem to have been sincere in their reform efforts, and have already gone further than they had intended to. There is more to do: for example, about 200 political prisoners are still behind bars. But by now reform has generated its own momentum, opening up possibilities that two short years ago seemed totally out of reach.

Everything is now in flux and change is accelerating. Even the constitution, supposedly the basis of the army’s continuing grip on the country, is up for official review by a parliamentary commission, initiated by the army itself through its parliamentary proxy, the USDP. Encouraged by the apparent willingness of reforming ministers like Shwe Mann and Aung Min to re-examine every aspect of life in Myanmar, exiles have been returning to provide much-needed technical expertise.

So there will never be a better time to draw up a proper federal constitution for the country, based on the principles of power- and resource-sharing between the Burman centre and the ethnic groups. Some at the Peace Centre argue that this is also an opportunity to set up a mechanism for redistributing wealth, based on each state’s income and population. This would help the federal idea along, especially as at the moment almost all the new foreign investment is going to the Burman heartlands, making existing inequalities worse.

Seize the moment

The army could probably be persuaded to exchange economic and political power for professionalisation. The aim would be to turn it from the rambling, low-wage, chicken-farming organisation that it has become, frequently implicated in torture and other gross human-rights violations, into a slim, modern, properly funded institution. Some officers are known to be in favour of this sort of transformation. But the new army would also have to be truly national, incorporating the Kachin, Karen and others, just as General Aung San originally envisaged. And the wilful discrimination against the Rohingya Muslims and others would have to end.

All this will take courage—and considerable help from abroad. But as this special report has argued, the risks of not undertaking such fundamental reforms are far greater than the risks of trying. All the economic and political progress so far could still founder on Myanmar’s old, deep divisions. That would be a tragic waste of a golden opportunity.

Suu Kyi for president?

Possibly, though many twists and turns still lie ahead

May 25th 2013 |From the print edition

THE NEW PARLIAMENT in Naypyidaw is proof that Thein Sein’s reforms have already far outrun his predecessor’s limited ambitions for “disciplined democracy”. When it first met in January 2011, stuffed with the pliant USDP victors of the rigged 2010 election and the 25% army block, the parliament did look like the rubber-stamping institution it was intended to be. But under the energetic leadership of the Speaker of the lower house, Shwe Mann, a former general and a member of the ruling military junta, it has become feisty, unpredictable and unafraid to challenge the president.

Like many other opposition MPs from the minority ethnic parties, Oo Hla Saw, the head of the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (RNDP), says that whereas in the early days of the parliament his questions on subjects like federalism and wealth-sharing in the states were banned, now “we can discuss these openly…it’s very positive and we are very happy about this.” Win Htein, a senior NLD MP elected in the by-elections of April 2012, says that parliament is now “very lively”. Even the USDP members are taking part more as regular lawmakers than as placemen for the army, judging proposals on their merits.

The people’s choice would undoubtedly be Miss Suu Kyi

Shwe Mann is an astute political operator and probably hopes to make a bid for the presidency in 2015, when the next general election is due. He is using parliament as a vehicle to advance his own agenda at the expense of Thein Sein, whose wings have been clipped by parliament on several occasions. In Myanmar’s system the MPs elect the president. Shwe Mann has formed an effective alliance with his most famous MP, Miss Suu Kyi, and has earned the respect of other opposition MPs for his willingness to listen and negotiate. He could be a compromise presidential candidate, bridging the differences between the army and the opposition parties, especially if the most popular choice for the top job is ruled out.

Lady in waiting

The people’s choice would undoubtedly be Miss Suu Kyi. She and her party, the NLD, have been the most obvious beneficiaries of Myanmar’s democratic opening. Her good personal rapport with Thein Sein, and more recently with Shwe Mann, has been crucial to moving the reforms along quickly. In return for Miss Suu Kyi’s help, Thein Sein has legalised the NLD and mostly called off the spooks and thugs. He also ensured that the by-elections of April 2012, the first elections since 1990 in which the NLD was allowed to take part, were free and fair.

Those by-elections proved that the iconic democracy advocate has lost none of her allure, even after decades of official attempts to discredit her. The NLD won 43 of the 44 seats it contested, often by huge margins. The USDP was trounced. It even failed to win any of the four seats in Naypyidaw, where many constituents work for the USDP-dominated government.

Those who supported the NLD were voting for democracy in general but also for “the Lady” in particular, to reward her for the sacrifices they feel she has made by giving up her family and her freedom for her country. She is also revered, even by many of her military opponents, as the daughter of Myanmar’s founding father, General Aung San. Politics in Asia tends to be dynastic, so her parentage gives her an overwhelming advantage over her rivals. Images of Miss Suu Kyi are often displayed alongside a favourite photo of her father in an outsize military overcoat. It was taken in 1947 when he was about to go to London to negotiate independence with the British government. Miss Suu Kyi was just two years old at the time. He was shot dead by political rivals later that year.

What made the NLD’s sweeping victory in the 2012 by-elections all the more extraordinary was that during military rule the party had been barely allowed to function. Almost all its leaders were imprisoned, some for decades, including long stretches in solitary confinement. Many of them have been remarkably forgiving of their former enemies. Win Htein, who spent over 20 years in jail, is now an MP and frequently has to mingle with them in parliament. He says that as a Buddhist he tries to banish feelings of anger from his heart and thoughts of revenge from his mind. “Anger is like fire,” he says, “and the fire will consume you so you will suffer more.”

Always a disciplined party, the NLD now has to transform itself from an underground protest movement into a potential party of government. Under Myanmar’s first-past-the-post electoral system the NLD would romp home in 2015 if it were to repeat its by-election victories at the national level. The USDP probably would not win a single seat.

The NLD held its first ever national congress in March to marshal its strength and streamline the way it picks its leaders and parliamentary candidates. The meeting was not an unqualified success. There was unprecedented criticism of Miss Suu Kyi for her autocratic style of leadership and unwillingness to accept new blood and new ideas. One critic, Khin Lay, who used to work closely with Miss Suu Kyi, complains that “the Lady says something, and that is policy.” There is little scope for real debates about ideas, she says: “Sometimes if we criticise ASSK we are called disloyal.” It will be a test of Miss Suu Kyi’s leadership to see if the NLD can now evolve into a broad-based party that is able to formulate sound policies on the economy, foreign policy and everything else without breaking apart. It has two years to get its act together.

Yet even if the NLD wins the election in 2015 it does not necessarily follow that Miss Suu Kyi will become president. As the constitution now stands she is barred from that office, thanks to a clause the army inserted specifically to rule her out, to the effect that anyone with a foreign spouse or children is ineligible. Miss Suu Kyi was married to an Englishman, Michael Aris (who died in 1999), and her two sons hold British passports.

The NLD is campaigning to change the 2008 constitution, which it never endorsed. The army was always thought likely to veto any constitutional changes, but intriguingly it may have changed its mind. Its minions in the USDP, led by Shwe Mann, realise that the only way to head off the NLD juggernaut in 2015 is to change the electoral system and introduce proportional representation (PR). This way they could at least avoid being completely wiped out: minority parties always do better under PR.

The constitution does not specify any particular electoral system, but it does say that the lower house should be made up of single-member constituencies, so the introduction of a PR system would require constitutional amendments. In March the USDP asked to set up a parliamentary commission to review the constitution, though without saying why. Clearly the best time for the party to change the constitution is when it still has a massive majority.

The ethnic parties, the parliamentary representatives of the Karen, Chin, Shan and other minorities also back a PR system. Many of them fear a landslide victory for the NLD almost as much as the USDP does because they view it largely as a party of Burman ethnic interests and do not trust it. There is talk of them combining to form an entirely new party, a sort of Federalist Party, to challenge both the NLD and the USDP. That would be much easier to achieve under a PR system.

It would be a gamble, but if the constitution were revised the NLD might concede a PR system in exchange for dropping the clauses barring Miss Suu Kyi from the presidency. Clearly much horse-trading in Naypyidaw lies ahead.