The Index Liquidity Riddle: More Is Less

March 25, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated March 22, 2013, 1:27 p.m. ET

The Index Liquidity Riddle: More Is Less

You would think that the whole point of a stock index is to be, well, an index of the stock market’s performance.

But thanks to the popularity of exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, stock indexes have in recent years been doing double duty as investment vehicles. At the same time, there have been subtle but important changes in the way indexes are constructed.

Bottom line: The indexes aren’t measuring exactly what they used to.

It is a lot easier to manage an ETF if the stocks that underlie it are easily traded. If, instead, the stocks are illiquid, there is a risk their prices will get artificially inflated when money flows into the ETF. The opposite can happen when money flows out.

One step index providers have taken to bolster liquidity has been to move from capitalization-based indexes, where the weight of each member is determined by the value of its total shares outstanding, to float-adjusted indexes. In the latter, shares that are unavailable to the public (such as stock held by company directors) don’t count toward a company’s weighting. Britain’s FTSE Group made the move to float-adjusted indexes in 2000, followed by MSCI MSCI +0.51% in 2002 and Standard & Poor’s in 2005.

But while switching float adjustment may improve an index’s liquidity profile, argue researchers at New York money manager Horizon Kinetics, it may also cut into its ability to generate returns. That is because many of the companies that have added oomph to indexes like the S&P 500 in the past did so at a time when a great many of the shares were held by insiders.

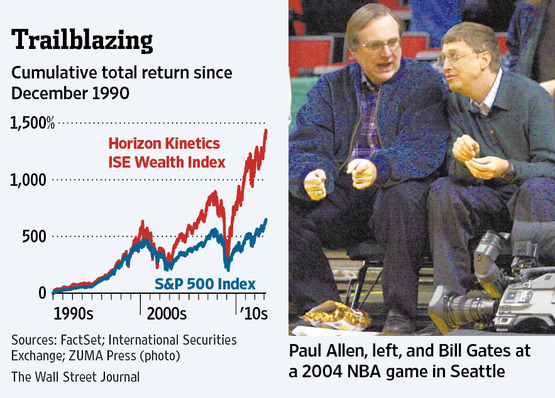

For example, when Microsoft MSFT +0.50% entered the S&P 500 in June 1994, the combined holdings of co-founders Bill Gates and Paul Allen, along with then-Vice President (and now chief executive) Steve Ballmer, represented about 40% of the company’s shares outstanding. By the end of 1999, the three had whittled their stakes down to a still-substantial 22% of the company.

From the end of 1994 to the end of 1999, Microsoft’s market capitalization swelled from $35.5 billion to $604.4 billion, a gain of about 1,600%. That accounted for about one-sixteenth of the S&P 500’s 267% increase in market capitalization over the period. If the S&P had been float-adjusted back then, Microsoft’s weight would have been lower, and it wouldn’t have helped lift the index as much as it did.

It wasn’t just Microsoft. Several S&P 500 companies with limited floats, including Wal-Mart Stores, WMT +1.57% Oracle ORCL -0.99% and Gap, GPS +0.68% served up outsize gains in the 1990s.

Indeed, Horizon Kinetics has constructed an index composed of companies whose wealthy insiders hold substantial stakes. This has beaten the S&P 500 by 2.7% annually on average over the past 20 years.

One reason could be simply that company founders hanging on to big chunks of their companies do so for a reason. So, by curtailing the S&P 500 weighting of companies whose executives have substantial skin in the game, Standard & Poor’s may have also limited the index’s future gains.

David Blitzer, who heads S&P’s index committee, points out that at the time the S&P 500 made the switch to float adjustment, most of the stocks in it had high floats. He said that under an informal rule dating back to at least the 1970s, stocks whose floats counted for less than half of their capitalization weren’t included in the index.

That said, while the S&P 500 has risen 26% since it completed its transition to float adjustment in 2005, it would be a percentage point higher if it was still a market-cap-weighted index. And this was a fallow period in the annals of corporate America.

If the U.S. enters a more dynamic phase, and recently minted companies flourish again, the S&P 500 may leave gains on the table. The same is true for investors in ETFs and other funds that track the index.