As India’s Rupee Drops, Foreign Firms Reel; Fear of Fed Retreat Roils India; Economic Weakness in Developing Nations Is Laid Bare as Easy Money Dries Up; Rupee exposes India’s corporate debt stack

August 21, 2013 Leave a comment

August 20, 2013, 1:59 p.m. ET

As India’s Rupee Drops, Foreign Firms Reel

NEW DELHI—As India’s economy shifted into low gear earlier this year, sales at the country’s largest car manufacturer also lost steam, falling nearly 7% in the second quarter from a year earlier. Now the auto maker, Maruti Suzuki India Ltd., 532500.BY -0.81% faces trouble on a new front: the rapid drop in the Indian currency. The rupee has slumped nearly 3% against the dollar since last Wednesday and roughly 15% since May. “If the rupee remains where it is, it is going to hurt everybody across sectors,” Maruti Suzuki Chief Financial Officer Ajay Seth said Tuesday. “All the fundamentals have become very difficult right now.”India’s tumbling currency and the possibility of slower growth are adding to the challenges confronting companies in India—just as some multinationals already were having second thoughts about investing here. Overburdened infrastructure, serious power shortages, difficulty obtaining land and government red-tape pose significant hurdles for business in India.

When India’s economy was growing at an average of more than 8% a year, as it did from 2004 to 2011, the prospects in the world’s second-most-populous nation outweighed the risks.

But with gross domestic product now growing at about 5%, that calculus has changed.

A series of high-profile foreign companies, including South Korean steelmakerPosco 005490.SE -0.77% and U.S. retailer Wal-Mart Stores Inc., WMT -0.48%recently have withdrawn, scaled back or delayed plans in India.

On Tuesday the rupee touched a new low of 64.11 to the dollar before recovering slightly. Meanwhile, foreign investors were net sellers on the Bombay Stock Exchange, helping pull its S&P Sensex index down 0.3% after already dropping more than 5% this month.

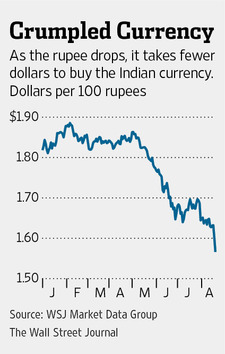

The rupee’s decline—as funds have flowed out of the country in anticipation that the U.S. Federal Reserve would curtail years of easy-money policies that made investing here attractive—has direct and indirect effects on companies here.

For Japan’s Suzuki Motor Corp.,7269.TO -0.13% which owns roughly 56% of Maruti Suzuki, the declining rupee could mean lower earnings at home and in India, a spokesman said.

Maruti’s import costs for parts from Japan increase as the rupee weakens. The Indian unit’s royalty payments to the Japanese company, which are denominated in yen, become more expensive as well.

Suzuki’s current earnings forecast assumes the rupee will fetch an average of 1.6 yen from last month through the end of the fiscal year in March, the spokesman said. Any weaker figure will hurt earnings, he said. The Indian rupee bought 1.53 yen on Tuesday.

The rising cost in rupees of imported components is being felt broadly by manufacturers. Electronics companies here, which use a high proportion of imported parts, already are raising prices in India.

Samsung Electronics Co. 005930.SE -0.32%last month raised prices of its mobile phones and other consumer electronics by 2% to 3% to compensate for the increased cost of importing components, a spokeswoman said.

Some industries stand to benefit handsomely from the weak rupee.

Large Indian information-technology outsourcing companies such as WiproLtd., 507685.BY -1.80% Infosys Ltd. 500209.BY +0.05% and Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. 532540.BY -1.85% generate more than 90% of their revenue from outside the country. Most have to convert foreign revenues into rupees. Consequently, a 1% decline in the value of rupee against the dollar may add to the profits of such companies by nearly 2.5%, said Sandeep Muthangi, an analyst with Mumbai-based brokerage firm IIFL Capital.

But the rupee’s drop indirectly raises borrowing costs. India’s central bank, moving to defend the currency and keep inflation in check, has nudged interest rates higher and could continue to do so if the currency continues to drop. That, in turn raises the price of borrowing for consumers and companies, weighing on economic growth.

“The falling rupee is a vote of no confidence against the government. Unless you address the fundamentals, nothing is going to change,” said Ravi Venkatesan, a former chairman of Microsoft Corp.’s India operation and author of a book on investing in India. “It is the underlying issues which should really be of greater concern: the growing [trade] deficit, weakening economy, difficulty in doing business.”

If the dropping rupee—and rising prices—force the government to open up the economy further, that might not be bad, Mr. Venkatesan said.

“We seem to act and reform only when there is a crisis,” he said.

—Santanu Choudhury in New Delhi, Dhanya Ann Thoppil in Bangalore and Hiroyuki Kachi in Tokyo contributed to this article.

Updated August 20, 2013, 10:14 a.m. ET

Fear of Fed Retreat Roils India

Economic Weakness in Developing Nations Is Laid Bare as Easy Money Dries Up

TOM WRIGHT, I MADE SENTANA and SUDEEP JAIN

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s plan to reduce monthly bond purchases is exposing the deep-seated fragility of India’s economy, unnerving investors and underscoring the risks to emerging markets at a time of rising global interest rates.

India’s stock market closed slightly lower Tuesday, after two days of steep declines. The rupee hit yet another fresh low against the dollar.

The malaise in India is the latest global ripple effect from a shift being considered at the U.S. central bank, following nearly five years of exceptional policy support for the American economy and financial markets.

During the era of low rates that followed the global recession, developing nations such as India, Indonesia and Thailand had no trouble attracting capital to boost growth. Imports soared as Asian consumers ran up debt to fuel purchases.

But as their export engines have sputtered, because of China’s slowing growth and uneven demand in the U.S. and Europe, these economies have started to run large current-account deficits, which occur when imports outweigh exports. As investors begin demanding higher returns for taking on risk, nations with large economic imbalances are getting punished.

“These economies definitely look suddenly a lot less impressive,” said Frederic Neumann, an economist with HSBC in Hong Kong. “Investors have woken up to the fact the Fed is serious about tapering,” or reducing bond purchases.

The flight from emerging markets hasn’t hurt stocks in richer economies. In the U.S., the Dow Jones Industrial Average remains just 4.1% below its all-time high even as market interest rates rise. On Monday, the yield on 10-year benchmark U.S. Treasury notes hit a two-year high of 2.884%, while the Dow fell moderately, dropping 70.73 points to 15010.74.

The selloff in Indian assets began in May, as Fed officials started discussing plans to pull back from the $85 billion of monthly bond purchases designed to bolster uneven U.S. economic growth. Seeing interest rates rise in rich-country markets such as the U.S., investors who had sought investments in faster-growing emerging markets pulled their funds.

The selloff has since spread to other developing nations, such as Indonesia and Thailand, which like India are exposed to rising global interest rates, thanks to budget and current-account deficits that mean they must borrow to finance daily spending.

The Indonesian rupiah fell to its lowest level in four years Tuesday. Shares have fallen 9% so far this week in Indonesia and were down 2% in Thailand on Tuesday, after a 3.3% fall Monday. Even Malaysia, which runs a current-account surplus, was hit, with the ringgit falling to a three-year low.

Few analysts expect the current clouds over the region to presage a full-blown crisis, like the one that slammed Asia in 1997-98. That is because governments and companies there have much lower external debt burdens than back then, and nations have ample stocks of foreign currency reserves.

But pressure on these economies is unlikely to abate anytime soon, economists and investors say.

India is particularly vulnerable to shifts in investor sentiment, because it needs foreign capital to finance a huge current-account deficit. The country, unlike some regional rivals such as Indonesia, also has built up considerable government debt.

India’s situation is particularly precarious, because it relies on huge energy imports to fuel its economy. Investment has ground to a halt because of the government’s failure to push through clear rules meant to open up sectors like retail and aviation to foreigners.

Analysts say Indian markets are caught in a vicious cycle where losses in one asset are undermining confidence in the others, and spurring further selling.

“The single biggest factor making investors nervous on India is the currency,” said Jyotivardhan Jaipuria, a research analyst with Bank of America Merrill Lynch in Mumbai.

As the rupee falls, it has negative implications for several aspects of the Indian economy. For instance, an eroding currency pushes up the cost of oil and other imported goods, like electronics, and stokes inflation, which is already about 10% for consumers. It also increases the government’s spending on fuel subsidies, potentially widening the fiscal deficit.

Analysts now expect the Reserve Bank of India to keep interest rates high in a bid to defend the rupee, but higher interest rates would hurt India’s economic growth, in turn making India less attractive to foreign investors.

In June, the Reserve Bank of India stopped a cycle of interest-rate cuts. In July, it effectively reversed course, making it more expensive for banks to borrow, forcing rates up in an effort to boost the rupee.

But that tighter liquidity also makes it much harder for companies to borrow to expand their businesses and repay their debt, adding to headwinds facing the already-slowing economy.

After a growth spurt from 2006 to 2011, when gross domestic product rose by an average of about 8% a year and raised hopes of India becoming a new Asian tiger, the country lapsed back into a plodding pace as economic reforms lost steam.

Economists have recently cut their target for India’s growth to as low as 5% for the year ending March 31, 2014, versus an expectation of 6.5% earlier this year.

In an effort to spark a comeback, officials last fall pledged fiscal rectitude and a more open economy. The government slashed fuel subsidies, helping shrink its budget gap to 4.9% of GDP in the year that ended March 31, from a projected 5.2%.

Last fall, India also moved to allow foreign companies such as Wal-Mart Stores Inc. to invest in Indian supermarkets for the first time, with a maximum stake of 51%. So far, investments have been limited by a lack of clarity on policies such as how much of a company’s products would have to be sourced locally.

Kaushik Basu, chief economist for the World Bank, said Monday that he expects India’s growth to fall further in the near term.

Investors also have become jittery because of a string of measures India has taken to stem the rupee’s decline.

India’s government, in an effort to narrow the current-account gap, has tried to curb gold imports and announced a plan to buy more of the country’s oil from Iran through what is effectively a barter mechanism. On Wednesday, the country reduced the amount of money residents and companies can send abroad, sparking fears of more-draconian measures.

The government says these moves aren’t a prelude to capital controls and that it doesn’t plan to impose restrictions on companies repatriating profits.

Last updated: August 20, 2013 6:51 pm

Rupee exposes India’s corporate debt stack

By James Crabtree in Mumbai

India’s inability to bolster its free-fallingcurrency or mend its worsening economy is causing increasing alarm in financial markets, but the problems facing some of the country’s largest industrial companies are if anything just as acute.

Leading billionaire businessmen such as Anil Agarwal of Vedanta, brothers Shashi and Ravi Ruia of Essar and Anil Ambani of Reliance have become only the most recognisable figures in a rising tide of corporate indebtedness that appears evermore threatening in light of the tumult in the country’s markets in recent days.

Vedanta smelter highlights India woes

Vedanta’s ambitious aluminium smelter project in India’s eastern state of Orissa was supposed to generate rich profits for the London-listed company’s self-made founder, Anil Agarwal, along with its minority shareholders, writes Amy Kazmin.

Instead it has come to embody the struggles of many of India’s largest industrial companies, as they find debts rising in the face of project delays and cancellations.

Vedanta Aluminium ploughed more than $6.7bn into the Orissa complex – including a 1m ton alumina smelter and aluminium refinery – before securing the most crucial element: permission to mine high-quality bauxite buried in the nearby Niyamgiri Hills, held sacred by a local animist tribe.

Now the company, which has spent the last 10 years battling local opposition, has reached a dead end in its quest for bauxite from the controversial site.

Last week, research from Credit Suisse revealed thatgross debt at 10 of the largest and most indebted such conglomerates topped $100bn for the first time over the last financial year, part of a wider trend playing out in struggling sectors from construction and infrastructure to metals and mining.

The result has put leverage in corporate India at its highest level since the late 1990s, according to Morgan Stanley, placing further strain on a banking system that has seen impaired assets rise from 4 per cent of total loans in 2009 to about 9 per cent this year and is likely to hit at least 12 per cent by 2015.

“Indian corporates are very overleveraged and while they often complain about government inaction, the real problem is that they are up to their eyeballs in debt and they haven’t done anything about it,” says one senior figure at a global bank, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Larger industrial conglomerates cause particular worries, given the scale of loans taken out during an infrastructure investment boom that followed the global financial crisis.

Essar is one example. A diversified conglomerate based in Mumbai, it has spent $18bn since 2007 building everything from oil refineries to steel mills and power plants – assets it describes as “world class”.

This left the company with net debt of $14bn last year, however, while its interest cover ratio is less than 1, a level that often suggests a company will struggle to pay the interest on its loans.

Prashant Ruia, Essar’s group chief executive, says such snapshots are an unfair measure of the health of industrial groups, given they show just the costs of investments, not the future income from projects only now coming on stream.

“We will see significant uptick in revenue and profitability in the next two years as these projects begin to deliver,” he says. “It’s like a building. When you are building a building your rental income is zero, but the moment the building is completed, your rental income goes way up.”

Even so, many analysts worry about the ability of other leading Indian industrial groups to repay their loans and the knock-on effects for the banking system if they instead end up being restructured or declared non-performing.

Some are more critical. “It really is a bit like a Ponzi scheme,” says one senior figure at a large international company based in India, describing the way some larger companies are able repeatedly to restructure loans with state-backed banks, which in turn are periodically recapitalised by infusions of government money.

The recent sharp fall in the rupee complicates this picture further, in particular for those holding India’s $225bn stock of dollar-denominated debts, more than half of which is unhedged, according to Morgan Stanley.

This includes further high-profile names, such as Bharti Airtel, the telecoms group, along with billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s energy-focused conglomerateReliance Industries and his younger brother Anil’s flagship Reliance Communications, the mobile operator – all of which are likely to face higher interest payments.

The rupee’s fall will also hit those relying on imports of foreign technology or raw materials, an area where India’s import-dominated economy is especially vulnerable and where depreciation is already increasing costs. “Price increases at a time when demand is low is a double whammy,” says Jamshyd Godrej, head of privately-held manufacturer Godrej and Boyce, part of the broader $3bn Godrej conglomerate.

Even companies in industries benefiting from currency depreciation are nervous. “We would like a stable currency in a narrow band. Whenever it runs up or down in a very volatile manner like recently it hurts us, all of your hedging strategies and everything are hit for six,” says Natarajan Chandrasekaran, chief executive of Tata Consultancy Services, the country’s largest IT outsourcer by sales.

The real problem is Indian corporates are up to their eyeballs in debt and they haven’t done anything about it

– Senior banker

The worry is that trends of recent weeks are only likely to worsen, with further falls in the rupee expected and recent spikes in bond yields causing particular problems for those companies needing to refinance debt this year.

Few analysts expect India’s larger industrial companies to go bankrupt, although the recent travails of Vijay Mallya,Kingfisher Airlines owner, show such things can happen from time to time, even with India’s notably lenient culture of bank forbearance.

Even so, rising bad debts are set to place increasing stress on the state-dominated banking system, raising pressure on the government to recapitalise strained lenders, while the companies themselves struggle to repair their balance sheets.

“Debt has increased very substantially and so has interest costs,” says Rakesh Valecha, head of corporate ratings at India Ratings & Research, a subsidiary of Fitch. “And if market volatility continues like this for the next couple of weeks, it will mean a lot more stress on balance sheets.”