The reckoning: Why India is particularly vulnerable to the turbulence rattling emerging markets

August 23, 2013 Leave a comment

The reckoning: Why India is particularly vulnerable to the turbulence rattling emerging markets

Aug 24th 2013 | MUMBAI |From the print edition

ON THE morning of August 17th most of India’s economic policymakers gathered in the prime minister’s house in Delhi. They were there to launch an official economic history of 1981-97, a period which included the balance-of-payments crisis of 1991. The mood was tense. India, said Manmohan Singh, the prime minister, faced “very difficult circumstances”. “Does history repeat itself?” asked Duvvuri Subbarao, the outgoing head of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). “As if we learn nothing from one crisis to another?”The day before Indian financial markets had had their rockiest session for many years. The rupee sank and stockmarkets tumbled. Money-market rates rose. The shares of banks thought to be either full of bad debts or short of deposit funding fell sharply. The sell-off had been made worse by new capital controls introduced on August 14th in response to incipient signs of capital flight. They reduce the amount Indian residents and firms can take out of the country. Foreign investors took fright, fearful that India might freeze their funds too, much as Malaysia did during its crisis in 1998.

India’s authorities have since ruled that out. But markets keep sliding. On August 20th the RBI said it would intervene to try to calm bond yields. The rupee has dropped to over 64 to the dollar, an all-time low and 13% below its level three months ago. It is widely agreed the country is in its worst economic bind since 1991.

India is not being singled out. Since May, when the Federal Reserve first said it might slow the pace of its asset purchases, investors have begun adjusting to a world without ultra-cheap money. There has been a great withdrawal of funds from emerging markets, where most currencies have fallen by 5-15% against the dollar in the past three months. Bond yields have risen from Brazil to Thailand. Some governments have intervened. On July 11th Indonesia raised its benchmark interest rate to bolster its currency. On August 21st its president said he would soon announce further measures to ensure stability.

India, Asia’s third-biggest economy, is more vulnerable than most, however. Economic news has disappointed for two years, with growth falling to 4-5%, half the rate seen during the 2003-08 boom. It may fall further. Consumer-price inflation remains stubborn at 10%. A drive by Palaniappan Chidambaram, the finance minister, to push through a package of reforms and free big industrial projects from red tape has not worked. An election is due by May 2014, adding to uncertainty.

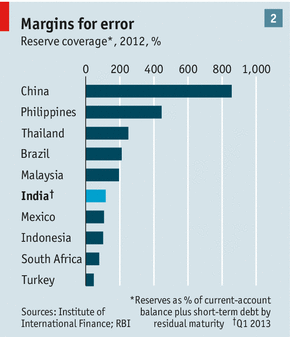

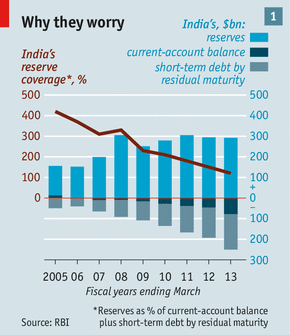

India’s dependence on foreign capital is also high and has risen sharply. The current-account deficit soared to almost 7% of GDP at the end of 2012, although it is expected to be 4-5% this year. External borrowing has not risen by much relative to GDP—the ratio stands at 21% today—but debt has become more short-term, and therefore riskier. Total financing needs (defined as the current-account deficit plus debt that needs rolling over) are $250 billion over the next year. India’s reserves are $279 billion, giving a coverage ratio of 1.1 times. That has fallen sharply from over three times in 2007-08 (see chart 1) and leaves India looking weaker than many of its peers (see chart 2).

It is therefore vital that foreign equity investors stay put. They own perhaps $200 billion of shares at current prices. They have sold only about $3 billion since May, but if they head for the exit India would have no defence.

This is not a repeat of 1991. When India last had a crisis Boris Yeltsin was about to stand on a tank in Moscow and Nirvana was hitting the big time. Things have changed in financial terms, too. Back then India had a fixed exchange rate, which the state almost bankrupted itself trying to defend—it had to fly gold to the Bank of England in return for a loan. Today India has a floating exchange rate and a government with almost no foreign-currency debt. A slump in the currency poses no immediate threat to the government’s solvency.

The pain will be felt in other ways. Private firms that owe most of India’s foreign debt will be under intense strain, particularly if the rupee drops further. Some will go bust. Market interest rates will stay high, causing a liquidity squeeze. All this makes life even tougher for India’s state-owned banks, which already have sour loans equivalent to 10-12% of their loan books. Inflation will rise. And the government’s finances will be under strain as the cost of its subsidies on imported fuel gets bigger.

There is probably little the authorities can do to shore up the currency in the short term. The rupee is one of the world’s most actively traded currencies and at least half the turnover is abroad. Privately, officials reckon the rupee’s fair value, taking into account India’s higher inflation and productivity over the past few years, is a little less than 60 per dollar, so the market has yet to overshoot wildly. Raghuram Rajan, the incoming governor of the RBI, is likely to take a hands-off approach.

That doesn’t mean the government will—or should. On August 19th it banned the import through airports of duty-free flat-screen TVs, which Indians can often be seen heaving through check-in at Dubai. It may seek to raise duties further on gold imports, which Indians are addicted to in part because it is seen as a hedge against inflation. Gross gold imports were 3% of GDP last year, blowing a huge hole in the external finances. History suggests the higher taxes on gold imports are, the worse smuggling gets. But India imports 800-odd tonnes of bullion a year. That’s a lot of gold to hide in suitcases.

The government will also try to persuade the Supreme Court to lift its ban on iron-ore exports, imposed after a series of corruption scams. At its peak this industry generated exports worth about 0.4% of GDP, although experts doubt that mothballed mines can be ramped up fast. The government may also cut fuel subsidies. That would reduce demand for imported fuel and help it hit a fiscal-deficit target of about 7% of GDP (including India’s states).

The longer-term solution to the balance-of-payments problem may be to ramp up India’s manufacturing sector, and thus its industrial exports. But that will take a big improvement in the business climate, not just a cheap currency. Despite the rupee’s 27% tumble in the past three years there is scant sign of global manufacturers shifting production to India.

India’s position could still get worse. But assuming things stabilise, when the official histories come to be written about 2013, what might they say? Most likely that the rupee’s slump caused a severe shock to the economy that made a recovery in growth rates even harder. But perhaps, also, that it prompted a more serious debate about the policies that India needs to become less vulnerable to the whims of an unforgiving world.

How India got its funk

India’s economy is in its tightest spot since 1991. Now, as then, the answer is to be bold

Aug 24th 2013 |From the print edition

IN MAY America’s Federal Reserve hinted that it would soon start to reduce its vast purchases of Treasury bonds. As global investors adjusted to a world without ultra-cheap money, there has been a great sucking of funds from emerging markets. Currencies and shares have tumbled, from Brazil to Indonesia, but one country has been particularly badly hit.

Not so long ago India was celebrated as an economic miracle. In 2008 Manmohan Singh, the prime minister, said growth of 8-9% was India’s new cruising speed. He even predicted the end of the “chronic poverty, ignorance and disease, which has been the fate of millions of our countrymen for centuries”. Today he admits the outlook is difficult. The rupee has tumbled by 13% in three months. The stockmarket is down by a quarter in dollar terms. Borrowing rates are at levels last seen after Lehman Brothers’ demise. Bank shares have sunk.

On August 14th jumpy officials tightened capital controls in an attempt to stop locals taking money out of the country (see article). That scared foreign investors, who worry that India may freeze their funds too. The risk now is of a credit crunch and a self-fulfilling panic that pushes the rupee down much further, fuelling inflation. Policymakers recognise that the country is in its tightest spot since the balance-of-payments crisis of 1991.

How to lose friends and alienate people

India’s troubles are caused partly by global forces beyond its control. But they are also the consequence of a deadly complacency that has led the country to miss a great opportunity.

During the 2003-08 boom, when reforms would have been relatively easy to introduce, the government failed to liberalise markets for labour, energy and land. Infrastructure was not improved enough. Graft and red tape got worse.

Private companies have slashed investment. Growth has slowed to 4-5%, half the rate during the boom. Inflation, at 10%, is worse than in any other big economy. Tycoons who used to cheer India’s rise as a superpower now warn of civil unrest.

As well as undermining 1.2 billion people’s hopes of prosperity, failure to reform dragged down the rupee. Restrictive labour laws and weak infrastructure make it hard for Indian firms to export. Inflation has led people to import gold to protect their savings. Both factors have swollen the current-account deficit, which must be financed by foreign capital. Add in the foreign debt that must be rolled over, and India needs to attract $250 billion in the next year, more than any other vulnerable emerging economy.

A year ago the new finance minister, Palaniappan Chidambaram, tried to kick-start the economy. He has attempted to push key reforms, clear bottlenecks and help foreign investors. But he has lukewarm support within his own party and faces obstructionist opposition. Obstacles to growth, such as fuel shortages for power plants, remain. Foreign firms find nothing has changed. Meanwhile, bad debts have risen at state-run banks: 10-12% of their loans are dud. With an election due by May 2014, some fear that the Congress-led government will now take a more populist tack. A costly plan to subsidise food hints at this.

Stopping the rot

To prevent a slide into crisis, the government needs first to stop making things worse. Those capital controls backfired, yet the urge to tinker runs deep: on August 19th officials slapped duties on televisions lugged in through airports. The authorities must accept that 2013 is not 1991. Then the state nearly bankrupted itself trying to defend a pegged exchange rate. Now the rupee floats, and the state has no foreign debt to speak of. A weaker currency will break some firms with foreign loans, but poses no direct threat to the government’s solvency.

And so the Reserve Bank of India must let the rupee find its own level. The currency has not yet wildly overshot estimates of fundamental value. Raghuram Rajan, the central bank’s incoming head, should aim to control inflation, not micromanage one of the world’s most traded currencies.

Second, the government must get its finances in order. The budget deficit has been as high as 10% of GDP in recent years. This year the government must hold down its deficit (including those of individual states) to 7% of GDP. It is already cutting fuel subsidies, and—notwithstanding the pressures in the run-up to an election—should do so faster.

This is not enough to fix the government’s finances, though. Only 3% of Indians pay income tax, so the government’s tax take is puny. A proposed tax on goods and services, known as GST, would drag more of the economy into the net. It is stuck in endless cross-party talks. If the government can rally itself before the election to push for one long-term reform, this is the one it should go for.

Last, the government, with the central bank, should force the zombie public-sector banks to recapitalise. In 2009 America did “stress tests” to repair its banks. India should follow. Injecting funds into banks would widen the deficit, but the surge in confidence would be worth it.

There are glimmers of hope: exports picked up in July, narrowing the trade gap. But India faces a difficult year, with jittery global markets and an election to boot. Even if it scrapes past the election without a full-blown financial crisis, the next government must do much, much more to change India. Over the coming decade tens of millions of young people will have to find jobs where none currently exists. Generating the growth to create them will mean radical deregulation of protected sectors (of which retail is only the most obvious); breaking up state monopolies, from coal to railways; reforming restrictive labour laws; and overhauling India’s infrastructure of roads, ports and power.

The calamity of 1991 led to liberalising reforms that ended decades of stagnation and allowed a spurt of fast growth. This latest brush with disaster could produce a positive legacy, too, but only if it persuades voters and the next government of the importance of a new round of reforms that deal with the economy’s flaws and unleash its mighty potential.