Lofty Profit Margins and Shrinking Share of GDP Going to Worker Compensation Hint at Pain to Come for Stocks

August 24, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated August 23, 2013, 5:24 p.m. ET

Lofty Profit Margins Hint at Pain to Come for Stocks

With Margins Near Record Levels, It Looks Like There’s Only One Direction for Shares to Go

MARK HULBERT

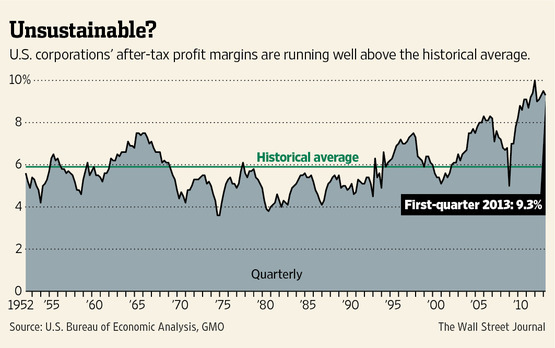

Profit margins at near-record levels—watch out below! If you are wondering what might prove to be the stock market’s Achilles’ heel, look no further than its dependency on near-record corporate profit margins. Any sizable decline would almost certainly translate into big losses for the stock market. Given the current high levels, such a retreat seems likely. Investors therefore may want to begin building up a healthy cash position to take advantage of lower prices in coming years.U.S. corporations, on average, currently report a profit of 9.3 cents for every dollar of sales, according to U.S. Commerce Department data—a profit margin of 9.3%. It has gotten only slightly higher than this over the past six decades: In the fourth quarter of 2011, it was 10%. The average since 1952 is 5.9%.

Profit margins in the past have exhibited a strong historical tendency to “revert to the mean,” according to James Montier, a visiting fellow at the U.K.’s University of Durham and a member of the asset-allocation team at Boston-based GMO, an investment firm with $108 billion under management. That is, above-average levels in the past have tended to quickly fall, just as below-average levels in the past have soon risen.

Consider all occasions since the early 1950s in which the profit margin rose to at least 6.9% or fell to at least 4.9%—one percentage point away from its historical mean, in other words. On average, it was back at its mean in just 4.8 years.

Mr. Montier says he thinks it isn’t unlikely it will take a similar period for the profit margin this time around to revert to its mean. And it is a matter of simple math to calculate where the S&P 500 will be in five years if margins drop to their average, once we make assumptions about sales growth and price/earnings levels.

The resulting picture isn’t pretty.

To be generous, let’s assume there won’t be a recession: Sales-per-share will continue to rise at the same pace it has since the bull market began in 2009—which is 1.7% a year—and the S&P 500’s P/E ratio (based on trailing earnings) stays constant at its current level of 16.7. If so, the S&P 500 in five years would be trading at 1183—nearly 30% lower than current levels. If corporate profit margins merely retreat half the way toward the historical mean, the S&P 500 in the summer of 2018 would trade at 1524—more than 8% lower than today.

What if corporate profit margins somehow don’t revert to their mean and stay at their current high level? Even then, the stock market would disappoint, since, in that scenario, earnings would grow no faster than sales. But, given the dual assumptions that sales growth will equal its 1.7% annual rate since 2009 and the P/E stays constant, that means the S&P 500 itself will therefore rise by just 1.7% a year.

In fact, given the assumptions, the only way for the stock market to rise at anything close to its historical rate of 10% annually over the next several years is for profit margins to rise even further than their already-lofty levels. While anything’s possible, Mr. Montier says the economic factors aren’t in place to support that. He reminds us that, in order for profit margins to widen, it isn’t good enough for the favorable conditions of recent years to persist. “Those conditions have to become even more favorable.”

Consider two of the factors often credited for the expansion of profit margins over the past several years: lower taxes and falling interest rates. These factors “will support higher profit margins in coming years only if they fall even further,” Mr. Montier argues, “and yet that seems highly unlikely, especially in the case of interest rates.”

Another factor contributing to expanding profit margins in recent years is the shrinking share of gross domestic product going to worker compensation, according to Robert Arnott, chairman of Research Affiliates, an asset-management firm with $150 billion under management. This trend also is unlikely to continue, because, if it were to do so, “the backlash would be so widespread that it could turn Occupy Wall Street into a mainstream event,” Mr. Arnott said in an interview.

Is there any way for the stock market to sidestep the bearish consequences of dwindling profit margins? One way would be for sales to rise much faster than they have since 2009. But that seems unlikely, Mr. Arnott continued. “Corporate sales growth historically has averaged about two percentage points less than GDP growth. Unless you are willing to bet on a huge upsurge in GDP growth, sales growth won’t be fast enough to make up for any significant drop in corporate profit margins.”

Another way the stock market could sidestep the bearish consequences of shrinking profit margins would be for the market’s P/E ratio to rise. Yet, since the S&P 500’s current ratio already is some 25% above its long-term average, that also seems doubtful, Mr. Arnott said.

Mr. Montier stresses that investors shouldn’t place heavier bets on other classes—such as bonds—just because the U.S. stock market’s potential is bleak. Instead, with only a couple of exceptions, his firm recommends clients build up cash and patiently wait for better opportunities. That isn’t because cash itself earns a very attractive return, he says, but because his firm doesn’t think there are many noncash alternatives right now that are worth the risk.

One option for where to park that cash is the Vanguard Prime Money Market Fund, with an expense ratio of 0.16%, or $16 per $10,000 invested.

The stock sectors Mr. Montier’s firm considers most attractive right now are U.S. high-quality (stocks of companies sporting “high and stable profits, with low leverage”), European value stocks (out-of-favor stocks trading for low ratios of price-to-book value), and, to a somewhat lesser extent, stocks in emerging markets. He doesn’t recommend investing more than a small fraction of your equity portfolio in any of these sectors, however, since “even these relatively attractive sectors aren’t compelling in an absolute sense.” He therefore thinks investors should keep cash available for the even-better opportunities he thinks will be available in coming years.

Examples of stocks satisfying the firm’s definition of “high quality” are Coca Cola,KO +0.55% Johnson & Johnson JNJ +0.92% and Microsoft MSFT +7.29% . An exchange-traded fund that invests in European value stocks is the First Trust Stoxx Euro Select Dividend ETF, with an expense ratio of 0.60%.

Two ETFs that invest in emerging-market stocks are the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets EEM +1.18% fund, with an expense ratio of 0.68%, and the Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets VWO +1.18% fund, with an expense ratio of 0.18%.

—Mark Hulbert is editor of the Hulbert Financial Digest, which is owned by MarketWatch/Dow Jones. Email: mark.hulbert@dowjones.com