Investors Prove More Selective in Latest Emerging-Market Selloff

August 28, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated August 27, 2013, 8:43 p.m. ET

Investors Prove More Selective in Latest Emerging-Market Selloff

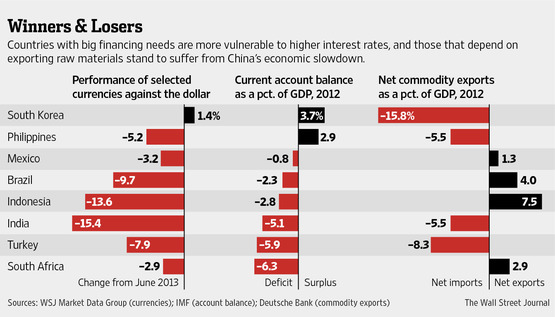

Even as currencies in India, Turkey, the Philippines and Malaysia plummet against the U.S. dollar, other developing countries have managed to avoid the selloff, showing that investors are differentiating among them. Mexico and South Korea, which were at the locus of past emerging-market meltdowns, have been relatively unscathed this time around, and a number of Eastern European economies also are holding up well. Investors have been punishing countries with large trade imbalances and foreign borrowings instead.“What we’re seeing lately is a bit more discrimination, says Luis Oganes, head of Latin America research at J.P. Morgan Chase JPM -2.32% & Co. “Investors are looking at the fundamentals of each country and choosing winners and losers.”

The monthslong rout was exacerbated Tuesday by jitters over the prospect of a U.S. military strike in Syria. The main triggers were expectations that the U.S. Federal Reserve is about to scale back its monetary stimulus, and concern that an economic slowdown in China will hurt the countries that send it raw materials.

Those economies that rely the most on short-term foreign money to fund trade deficits, including Turkey and India, or that have large overseas debt, have borne the brunt.

Turkey’s central bank, which increased its target for overnight lending to 7.75% last week, said Tuesday that it wouldn’t raise interest rates further, a tacit admission that efforts to tighten liquidity have failed.

India’s currency has continued its free fall despite several attempts by the central bank to slow the flow of money out of the country. Some economists blamed a costly bill moving through India’s Parliament to increase food subsidies for undercutting confidence. Traders said the Reserve Bank of India likely sold dollars at least once during Tuesday trading.

In Indonesia, the central bank called a special meeting of its board for Thursday after recent efforts failed to stop a precipitous slide in the rupiah.

By contrast, those nations that used the era of easy global money to overhaul their economies are seeing benefits. South Korea dramatically cut its exposure to foreign short-term debt. Mexico instituted economic changes aimed at boosting growth and attracting long-term capital, such as investment in factories.

Central bankers and academics gathered last weekend in Jackson Hole, Wyo., agreed that countries with low government debt, a healthy banking system and sound monetary policy have proved more resilient.

“Fundamentals are fundamental,” said Terrence Checki, the New York Fed’s executive vice president in charge of the emerging-markets and international-affairs group. “Experience suggests that one cannot overstate the importance of sound economic management, strong fiscal positions, credible proactive monetary policy and rigorous financial-sector oversight.”

Overall, emerging markets have undergone a dramatic reversal of fortunes this summer. The tide of money that sloshed into emerging markets when developed nations pushed their own rates to historic lows is now receding. Since the end of May, there have been 13 consecutive weeks of net outflows from emerging-market bond funds, according to J.P. Morgan.

Many of the struggling nations’ currencies are down 15% over the past year. But the Mexican peso and South Korean won are in positive territory.

Central and Eastern Europe stock markets, meanwhile, are up 1.2% in the past three months, compared with an overall emerging markets decline of 7.5%, according to index provider MSCI.

Exporting nations like Poland and Hungary are running trade surpluses and look set to benefit from a pickup in growth in Western Europe, especially Germany.

Until recently, places like India, Indonesia, Turkey and Brazil were booming, buoyed by exports of raw materials and other goods to China. Governments, households and companies there used the period of cheap credit to fund spending, rather than long-term investments.

Now, Chinese demand is slowing and many of these nations are running large trade deficits and have sizable overseas borrowings. These are proving harder to finance as U.S. interest rates move higher, attracting global funds back to U.S. assets.

Barry Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, said such countries had a chance to rein in government spending, raise taxes and open more sectors to foreign investment, but feared the political consequences of doing so.

“During the good times, they had a window to do serious pro-growth reforms and they didn’t,” he said.

Some nations, instead, have attacked the Federal Reserve. Brazilian authorities until recently blamed the U.S.’s low interest rates and the ensuing weak dollar for hurting Brazil’s export competitiveness.

With the real now much weaker, Brazil Finance Minister Guido Mantega on Monday made the opposite case, blaming the Fed for giving out confusing signals over the end to its era of low interest rates and money-printing.

Brazil is also seen as particularly vulnerable to slower growth in China, the No. 1 destination for its raw materials.

Mexico has had relatively lackluster growth compared with Brazil and other emerging markets, partly because of its close links with the U.S. during a difficult economic period. As a result, it embarked on a string of ambitious overhauls in its telecommunications, energy and education sectors to shake up its hidebound economy and try to bolster growth.

Now its association with the U.S. is turning into an asset. Though Mexico’s growth is still sputtering, it is expected to pick up speed as the U.S. continues its recovery. Mexico has little exposure to China.

In Asia, analysts point to South Korea as a country that has gotten stronger since it was hit by the 2008 financial crisis and the Asian financial crisis a decade before that. Short-term external debt was found to be the Achilles’ heel of South Korea’s financial system and the government has since worked hard to keep it at a manageable level.

“Korea learned after the 2008 crisis,” said Ju Wang, a Hong Kong-based foreign-exchange strategist at HSBC. “It is the one country that has been de-leveraging rather than re-leveraging in Asia.”

Fearing a recurrence of the sudden, destabilizing outflows, the South Korean government has implemented measures to slow the flow of hot money into and out of the economy.

It seems to have worked: The ratio of total short-term debt against the country’s foreign-exchange reserves stood at 36.6% at the end of the second quarter, down from close to 80% in 2008.

South Korea’s external short-term debt was around $190 billion in 2008, Ms. Wang said, and has since been brought down to around $120 billion. During the period, short-term external debt in India and Indonesia has almost doubled.

“Our country seems to be differentiated,” from other Asian economies, the South Korean Finance Minister Hyu Oh-seok said last week. “Money is still flowing into the country.”

Some analysts say the emerging-market selloff is overdone and predict that better-managed developing nations will bounce back. After all, the era of easy money may be coming to an end, but it isn’t over yet.

Even after the Fed starts winding down its massive bond-buying program, probably later this year, central banks in the U.K. and Japan are likely to continue theirs. And the Fed isn’t expected to start raising interest rates until at least 2015.

“Certainly the best of the party is already behind, but the party’s not over,” said Mr. Oganes. “I think we’re still going to have low interest rates for quite some time.”