In Turmoil, Emerging Markets Raise Rates; Move by Indonesia Follows Brazil, Turkey; Trend Threatens to Deepen Slowdown

August 30, 2013 Leave a comment

August 29, 2013, 7:51 p.m. ET

In Turmoil, Emerging Markets Raise Rates

Move by Indonesia Follows Brazil, Turkey; Trend Threatens to Deepen Slowdown

THOMAS CATAN in Washington, SHEFALI ANAND in Mumbai and TOM MURPHY in São Paulo

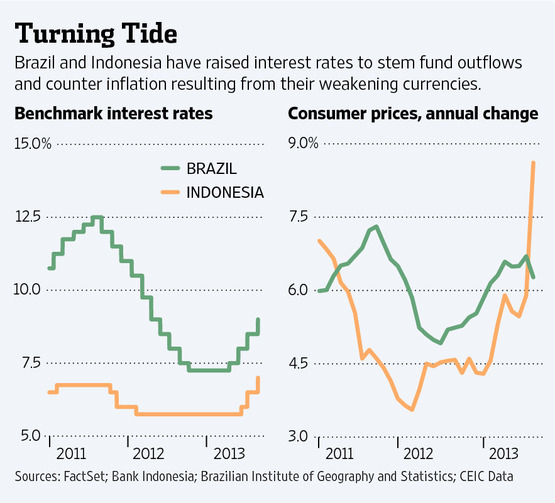

Major emerging-market central banks are moving to raise interest rates in an effort to stem an exodus of cash, in a trend that threatens to intensify an economic slowdown across the developing world. Indonesia raised its benchmark rate by half a percentage point on Thursday, one day after a half-point increase by Brazil and a week after a rate increase by Turkey. Other developing economies are under mounting pressure to tighten credit to support their weakening currencies. Brazil’s central bank hinted at further increases to come.The bonds, currencies and stock markets of many developing nations, including India, Turkey, South Africa, Brazil and Indonesia, have been hit in recent weeks as investors brace for the U.S. Federal Reserve to begin scaling back its $85 billion-a-month bond-buying program.

The Fed’s ultraeasy monetary policies over the past five years sent a wave of money sloshing into developing nations as investors sought higher yields, pushing up their currencies and stock markets. Now that tide is reversing.

Investors are particularly concerned about the countries most dependent on cheap foreign financing, such as India, Turkey and South Africa. “The more money pulls out, the worse these places look and the more people fear that they won’t be able to get their money out,” said Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington think tank.

Raising interest rates can help stanch the outflow of capital by making a country’s assets more attractive to investors by boosting the return on assets held in the country. Rate increases are also sometimes prescribed to counter inflation as a currency weakens, which raises the price of imported goods.

But higher rates can also curb growth. In Indonesia, for now, that effect isn’t expected to be too severe. Capital Economics, aneconomic-research firm, trimmed its growth forecast for the country this year to 5.5% from 6%.

But Brazil and many other developing nations are already struggling to keep their economies from stalling as China slows and reduces its purchases of raw materials from the rest of the world.

Last year, the Brazilian central bank was lowering rates to historic lows in an effort to rekindle growth. But inflation has long been the bête noire of an economy that suffered from four-digit price rises in the 1990s, and the central bank isn’t taking any chances. Its rate increase Wednesday was the fourth in a row.

“It’s true that you need high interest rates to combat inflation,” said Ilan Goldfajn, chief economist at Brazil’s Itau investment bank and a former central-bank official. “But high rates also make business investments more risky. Right now, we’re headed for growth of no more than 2% this year.”

Other major emerging markets are facing pressure to boost their own interest rates despite sputtering growth.

The value of India’s rupee has fallen by a fifth against the U.S. dollar since the beginning of May. The Reserve Bank of India’s initial response was to stop easing monetary policy, holding benchmark interest rates steady in June and July. When the rupee kept falling, the RBI limited the amount of money banks could borrow from it.

Investors saw that as effectively raising interest rates, at a time when India’s economy was growing at its slowest pace in a decade. Bonds and stocks sold off after the RBI’s steps. Yields on both short- and long-term rupee bonds jumped.

Some analysts say the incoming Indian central-bank governor may have no choice but to raise interest rates sharply, much as Fed Chairman Paul Volcker did in the U.S. in the 1980s.

South Africa is in a similar bind. Authorities want to halt declines in its currency, which has lost nearly a quarter of its value against the dollar over the past year but are reluctant to smother already weak growth.

Inflation reached an annual rate of 6.3% in July, but when South African central-bank officials meet to discuss rates again next month, they will be loath to raise rates in an economy struggling to meet forecasts for 2% growth this year, analysts say.

Some investors worry that they could see a repeat of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, or the stampede out of emerging-market currencies a decade later in 2008. But there are reasons to believe it won’t be that bad.

Most emerging-market currencies today are allowed to float, so central-bank officials don’t have to defend a fixed exchange rate as they did during the Asian crisis. The government debt levels of countries like Indonesia, India and Brazil aren’t particularly high and are denominated mainly in local currency.

“While the selloff has been sharp, we do not view the past couple of months as the start of a broader [emerging-market] crisis,” wrote Bank of America Merrill Lynch in a note to clients Thursday.

Can Brazil’s Currency Be Saved?

One almost feels sorry for Brazil’s central bank President Alexandre Tombini these days. The man charged with steering the monetary policy of the world’s sixth largest economy has a lot to handle.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has signaled it will finally reduce its quantitative-easing policy, a move that spells the end of the easy money that has helped Brazil’s economy coast for years. This has contributed to an initial blow to the Brazilian real, which last week dropped to its lowest level in 4 1/2 years. The currency is now down about 11 percent against the U.S. dollar in the past three months according to Bloomberg data. Meanwhile, yesterday the central bank raised its lending rate by 50 basis points in a signal it plans to keep inflation below 6.5 percent — the government’s upper bound on its target range — despite its exchange-rate woes.

So Tombini may have made a smart decision when he skipped the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole, Wyoming, symposium last week and on Aug. 22 launched a $60 billion intervention plan using currency swaps and loans to stem the decline. By using derivatives the bank avoids an immediate loss of reserves to defend the currency.

The real jumped the most in almost two years after the announcement. Martin Redrado, Argentina’s central bank before he was ousted in 2010 by left-leaning President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, gave the measure a thumbs up in an Aug. 23 tweet: “Brazil shows how economic policy must stabilize the dollar in uncertain times. They will use US$60 billion in reserves to achieve it.”

Brazil’s Folha de S. Paulo newspaper also approved in an Aug. 24 editorial, titled “An exchange tranquilizer,” arguing the move “contributes to quell the protests and alleviate the fears of lack of control over the exchange rate, which could erode even more the confidence of economic agents.”

The jury is still out, however, on how successful the plan will be in the long term. As the Fed’s moves become clearer, more investors will probably continue to pull their money out of emerging-market economies. Brazil’s O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper discussed such doubts in an Aug. 25 editorial: “With foreign reserves exceeding US$370 billion, the Central Bank could use part of that money to address the instability. But the bank has followed a prudent approach and it’s hard to say, for some time, if an alternative measure, burning some dollars, would be more effective.”

The key issue here is how to measure that effectiveness. If the ultimate goal of the program is to offer a limited lifeline to investors and companies with dollar-denominated debt — as financial flows head back to developed markets — that may effectively help some investors get out of a jam. Brazilian companies have already seen their debt jump 2.9 percent in July, largely due to a weaker real, according to credit bureau Serasa Experian. But if the bank hopes to somehow restore its credibility, the plan may be too little too late. Already, market participants sense Brazil’s move may not be enough.

Guido Mantega, Brazil’s finance minister, tried to instill respect in the central bank’s might, warning investors in an interview with Folha de S. Paulo published over the weekend, that those eager to speculate “may win, but they can lose because the exchange rate floats. So it is imperative to be careful.”

Mantega claims that “pressure of the dollar, in our case, doesn’t respond to capital flight, or a loss of reserves, as in other countries. Here it is hedging and speculation.” But that paints an incomplete picture of what ails Brazil. Poor infrastructure, high taxes, the government’s penchant for meddling in business and generous government spending makes Brazil’s economy vulnerable. This is hardly an encouraging picture once improving fortunes in developed markets offer investors less risky opportunities for their money.

Rodrigo Constantino expressed what many Brazilians were thinking in an Aug. 21 Veja magazine column titled: “The dollar rises and reaches R$2,45. Tombini cancels trip. Brazil is the ugly duckling of the world!” Constantino argues that the government’s “official excuse that this is a global phenomenon loses strength every minute. The problem is ‘made in Brazil’.”

Estado’s Aug. 25 editorial agreed that President Dilma Rousseff’s government could do more at home: “The uncertainty in relation to the Brazilian economy could be much smaller, if the Executive presented a clear plan of administration of public accounts, without makeup, and if it assumed a credible commitment to fiscal responsibility.”

Tombini’s central bank has certainly become a part of the problem as well. Under his mandate the bank continued to cut interest rates to stimulate the economy even as President Dilma Rousseff’s government showed a disregard for fiscal discipline. Just as Brazil’s economic troubles are in many ways self-inflicted, any loss of credibility by Brazil’s central bank is largely Tombini’s doing.

(Raul Gallegos is the Latin American correspondent for the World View blog. Follow him on Twitter. To contact the author of this article: Raul Gallegos at rgallegos5@bloomberg.net.)