A Toxic Subprime Mortgage Bond’s Legacy Lives On; The story of CWABS 2006-7—its borrowers, its investors and others touched by it—is the financial crisis seen from inside

September 13, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated September 12, 2013, 9:07 p.m. ET

CRISIS PLUS FIVE

A Toxic Subprime Mortgage Bond’s Legacy Lives On

The story of CWABS 2006-7—its borrowers, its investors and others touched by it—is the financial crisis seen from inside

MICHAEL CORKERY and AL YOON

At the core of the financial crisis was a creature called a subprime mortgage bond, and among the more toxic was one with the bland name of CWABS 2006-7. Made entirely out of loans from Countrywide Financial Corp., the bond was so battered by delinquencies in 2009 it appeared that nearly all of the thousands of mortgages inside the bond could default. One might think that today, such a relic of misbegotten lending would be as dead as orbiting space junk. Instead, CWABS 2006-7 is alive and well, a sought-after asset that has made big profits for savvy investors. A senior slice of it now trades at 91 cents on the dollar, having come nearly all the way back.That has been a boon for firms such as bond giant Pimco, whose stake in the Countrywide bond has helped make one of Pimco’s funds a top performer in its category.

At the same time, the bond has affected the lives of struggling Florida homeowners, some unable to make their payments and others, such as Amanda Gavini of Fort Myers, determinedly continuing to do so at above-market mortgage rates.

For others still, such as an immigrant from Russia named Alimzhon Iznurov, the bond and the homes tied to it have spelled an opportunity to snap up housing for their families at a bargain price.

The story of the bond called CWABS 2006-7—its borrowers, its investors and others touched by it—is the financial crisis seen from inside, illuminating complexities that often upended expectations and dealt widely differing fates to its many participants.

The Wall Street Journal, using real-estate records and the bond’s financial reports, tracked down three dozen homeowners whose loans are bundled in CWABS 2006-7. Few knew that or were aware of the possible effect this could have on their mortgage.

CWABS 2006-7 appeared in June 2006 as the run-up in home values and Wall Street’s mortgage-securitization machine hit peak velocity, fed by newfangled lending that enabled millions of people with spotty credit to become homeowners.

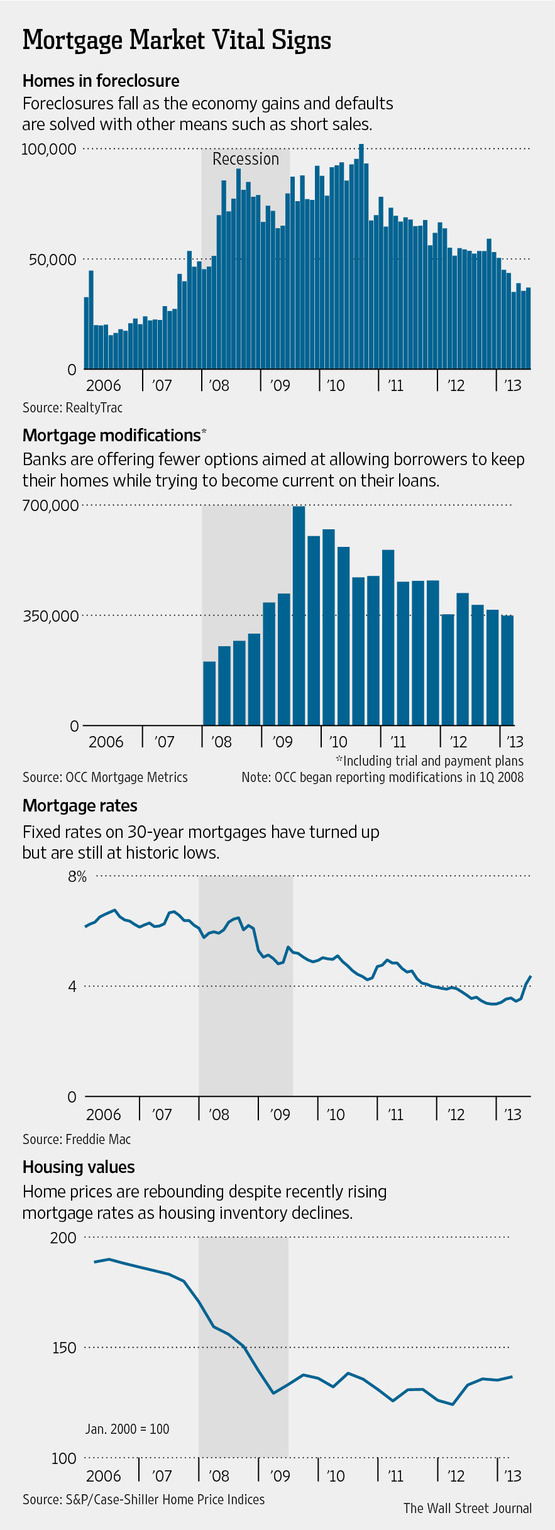

These were the final months before the realization sank in that many borrowers couldn’t repay, a notion that undermined subprime-mortgage bonds and set off a chain reaction engulfing mortgage-finance firmsFannie Mae FNMA -7.69% and Freddie Mac,FMCC -6.54% major banks and even the world’s biggest insurance company.

Countrywide bundled 5,954 of its subprime loans into the bond, loans carrying interest rates as high as 15% but with an average of 8.5%. Some included special features to accommodate people less able to buy, such as letting them pay only the interest at first. Countrywide offered pieces of the bond for sale, the highest-yielding slices for those willing to bear the most risk and vice versa.

One of the largest initial investors was Freddie Mac, which put up more than $300 million to buy a top-rated slice at 100 cents on the dollar. Part of the rationale for government-sponsored Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae was that such investing helped more Americans afford to become homeowners, securities filings by the mortgage firms said.

A lawsuit later filed by Freddie Mac’s overseer, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, said that Fannie and Freddie poured more than $26 billion into Countrywide residential mortgage-backed securities from mid-2005 to early 2008. The bonds were “supposed to represent long-term stable investments,” said the suit, adding that instead, Countrywide borrowers defaulted at a “staggering” rate.

The suit in New York state court claimed that Countrywide had doled out loans that people weren’t suited for and couldn’t afford. Defendants Countrywide and its new owner, Bank of America Corp.,BAC -1.16% dispute the claims in the suit, which is still pending.

In early 2009, as U.S. unemployment rose and home prices fell, “people were starting to consider the possibility that every loan in [the bond] would default,” said Cory Lambert, vice president of analytics at BlackBox Logic LLC, a mortgage-bond research firm. Delinquencies were rising so fast “there was no telling when or if they would ever level off.”

The bond slice owned by Freddie Mac was down more than half in value by the summer of 2009. That was when Countrywide borrower Donald Mudd first started missing his payments.

He and his wife, Patricia Starr, had gotten their loan in March 2006—about three months after Mr. Mudd emerged from a personal bankruptcy involving unpaid medical bills.

“I was surprised they approved me right after a bankruptcy,” said Mr. Mudd.

The couple received a $171,000 adjustable-rate loan from Countrywide, county records show, and put down $10,000 to buy a two-bedroom house in Port Charlotte, Fla., a retirement haven on the Gulf of Mexico where home values soared 63% from 2004 to 2006. Countrywide put the 30-year, 8% mortgage into CWABS 2006-7.

With his business of selling water-filtration systems hitting headwinds, Mr. Mudd discussed with Bank of America the possibility of changing his loan.

The government had just created a plan called the Home Affordable Modification Program, or HAMP. Mr. Mudd said the bank rejected him because the investor in his mortgage didn’t participate in the program.

A spokeswoman for Bank of America said it has no record that was the reason Mr. Mudd was denied a loan modification that year. She said the problem was that Mr. Mudd’s approximately $1,200 monthly loan payment in 2009 didn’t consume a big enough share of his income.

By this time, the riskiest slices of CWABS 2006-7 had been hammered by loan defaults, and losses were spreading toward senior slices, once rated triple-A, that often were owned by large financial institutions. For banks, the sinking value meant having to hold more reserves against losses, plus a threat of huge losses if they tried to unload the bonds in a crumbling market.

The fate of bonds such as CWABS 2006-7, in other words, was strangling banks’ lending ability—at a time when the economy needed it.

To put a floor under the bonds, the Treasury Department helped firms willing to step in and buy some. It created a taxpayer-funded initiative called the Public-Private Investment Program, or PPIP, through which the U.S. provided debt and equity investments to nine bond buyers, totaling $18.6 billion.

For these investors, the government financing added five percentage points to returns, estimates one participant, New York hedge-fund firm Marathon Asset Management. The government made some unusual requests, including asking Marathon to build a wall in its trading floor to separate PPIP trades from its other business, though Marathon never actually built the wall.

While buying some subprime bonds through the program, Marathon invested in other bonds outside of it, including CWABS 2006-7. The firm invested starting in early 2009 and throughout that year as the price dipped and then started to recover, according to people familiar with the trades.

About 43% of the mortgages in the bond were from California and Florida, hard-hit markets that Marathon figured would have solid recoveries.

Marathon sold its holdings in the bond throughout 2010. The firm declined to say how it made out, but the bond was recovering during this time.

The PPIP “not only established a bottom but it had the effect of facilitating a recovery in the asset class,” said Andrew Rabinowitz, Marathon’s chief operating officer.

The federal support wasn’t the only thing buoying CWABS 2006-7. It also benefited from steady payments by homeowners such as Mrs. Gavini in Fort Myers.

With her husband, she paid $398,000 for their three-bedroom house in April 2006, taking out two Countrywide loans, with interest rates of 11% and 7%. By late 2009, she figured the house was worth only half what she owed on it. But despite being “underwater,” she has never stopped making payments on the loans, monthly payments that now total $3,000.

“I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night” not making the payments, said Mrs. Gavini, a mother of two young children who works as a sourcing manager for a women’s-apparel retailer.

Her resolve to pay is just part of the reason the bond continues to gain from Mrs. Gavini’s situation. The bond also benefits because she is stuck with her interest rate, which is 7% in the case of her loan that is in the bond.

After steady repayment for seven years, plus employment, Mrs. Gavini has good credit, so that refinancing at today’s low rates into a prime loan might bring her monthly payment down by nearly half, mortgage brokers say. But because they owe more than the home is worth, she and her husband, Stephen Gavini, can’t refinance.

There is, in fact, a federal program that lets some borrowers in this fix refinance. Called HARP, for Home Affordable Refinance Program, it allows homeowners to lower their payments by extending the life of the loan or dropping their interest rate.

But to qualify, mortgages must be guaranteed by a government-sponsored firm such as Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. While those firms could invest in bonds stuffed with subprime mortgages, they didn’t guarantee such mortgages. That left out Mrs. Gavini.

“It’s not fair,” she said. “All we want to do is get refinanced.”

In its current form, Mrs. Gavini’s mortgage is valuable to the investors in CWABS 2006-7, given its interest rate and steady repayment.

In the lingo of the mortgage-bond industry, her high-rate loan is “trapped” in the CWABS 2006-7 bond.

As various other loans have fallen out of the bond—through foreclosures, sales of the homes and other routes—the Countrywide bond has become more and more concentrated with loans such as Mrs. Gavini’s that are current, enhancing its value.

In some cases, the loans in it are current because of government munificence.

Carolyn Culbreth, the owner of a single-story house near Interstate 95 in the eastern Florida city of Palm Coast, hasn’t made a mortgage payment on her own since March 2012.

Unemployed through all of last year, the 62-year-old now earns $9 an hour working at home for a call center offering billing and other customer service for cable, Internet and phone companies. She recently took in her son and grandson to live with her.

In August, Bank of America denied her latest request for a modification of a mortgage that Countrywide made. The reason it gave was that the investors in her mortgage—the holders of CWABS 2006-7—didn’t participate in a modification program designed to help unemployed homeowners.

But a government program has covered the payments Ms. Culbreth missed and her most recent ones. The state of Florida has done so through a “Hardest Hit Fund” that funnels federal money to strapped homeowners. The subsidy is technically a loan, but it will be forgiven if Ms. Culbreth stays in the house for 5½ years after the arrival of her last subsidy payment.

That day has come. The program has a maximum benefit, which Ms. Culbreth just hit. She doesn’t know how she will be able to afford her $1,451 monthly payment without the subsidy. “I may end up having to walk out of this house,” she said.

Years of modification attempts and state subsidies don’t appear to have changed a basic fact of Ms. Culbreth’s homeownership, which is that she can’t afford the mortgage Countrywide gave her. Today, she owes more than when she first took out the loan in 2006.

Asked about Ms. Culbreth, Bank of America’s spokeswoman said now that she is employed, the bank plans to contact her to see if it can help modify her mortgage.

The rising value of the CWABS 2006-7 has benefited not just from its growing concentration of borrowers current on their mortgages but also from the courtroom success of investors.

In June 2011, Bank of America agreed to pay $8.5 billion to settle investor claims that Countrywide had lent to people who couldn’t afford to repay, leading to losses on CWABS 2006-7 and 529 other Countrywide mortgage bonds.

The settlement still isn’t final. Some investors say it covered only a fraction of the losses on the bonds. Nonetheless, traders said it has lifted the value of assets such as CWABS 2006-7.

Some of the investors who suffered losses on Countrywide bonds early on, and were part of the lawsuit, spotted opportunity later and quickly got aboard again. Among them giant money managers BlackRock Inc. BLK +0.19% and Pacific Investment Management Co., the Allianz SE unit known as Pimco.

In mid-2011, as BlackRock and 21 other investors were hammering out their settlement with Countrywide, a BlackRock fund started purchasing a senior slice of the bond, according to research firm Morningstar Inc. By early 2012, after this piece of the bond had risen 44% in value, BlackRock had sold this stake.

As for Pimco, it poured $31 million into CWABS 2006-7 throughout 2012, a period during which the price increased 11%, and still held the investment as of March, according to Morningstar.

The Pimco bond fund that holds part of CWABS 2006-7, Pimco Income A, is in the top 6% of funds in its category over the past five years, according to Morningstar. “Its mortgage stake has been on fire,” a Morningstar analyst wrote in late 2012.

CWABS 2006-7 has created opportunities beyond big investment firms.

Mr. Iznurov, the native of Russia, spent months sniffing around in Florida for a low-price house. A Muslim, he said he came to the U.S. from Russia in 2005 to escape religious tensions.

He finally found the right property last year in Jacksonville, Fla., a modest ranch house in a development called Summer Trees, which offered him a chance to relocate his wife and two rambunctious children from a cramped apartment.

The loan on the house, part of CWABS 2006-7, was both delinquent and underwater. The loan servicer, or firm that collects mortgage payments, agreed to let the homeowner do a short sale—a sale for less than the sum owed that is a way to avoid foreclosure and move on.

The bond investors swallowed a loss on the original $121,600 loan as Mr. Iznurov bought the house for $77,000.

The previous owner had a 9%-interest subprime loan. Mr. Iznurov’s mortgage isn’t subprime. He has a loan insured by the Federal Housing Administration with an interest rate of 3.65%.

“That’s the market,” Mr. Iznurov says. “Somebody lose, somebody win.”

Mr. Mudd, the water-filter salesman, fears he could be about to lose.

On a rainy afternoon this summer, he sat in his living room in Port Charlotte with the shades drawn and the lights off. A stack of bank documents 13 inches tall was on his kitchen table.

The year after being turned down for a loan modification, Mr. Mudd again applied for a modification in February 2010.

A year of back and forth followed. He said he would fax his pay stubs and tax returns, and the bank would tell him they were outdated and ask him to send the documents again. “They would do this over and over and over again,” he said.

A Bank of America spokeswoman said that Mr. Mudd’s experience was “unusual.” She added that since then, “we’ve made significant improvement in our processes.”

In February 2011, the bank agreed to lower Mr. Mudd’s interest rate to 7.3% from 8.37%. But as often happens with modifications, the change didn’t lower his monthly payment. Because the mortgage revision had to cover delinquent past payments, it produced, despite a lower interest rate, a higher monthly bill, $1,323.

In his case, the modification was later canceled when Mr. Mudd didn’t keep up with the new, higher payments.

The Bank of America spokeswoman said, “We’ve been helping Mr. Mudd since 2008, offering him multiple modifications to help him keep his house.”

In April, the trustee for the investors of CWABS 2006-7 filed notice in court seeking to foreclose.

On May 29, Mr. Mudd received two more letters from Bank of America. One suggested he consider a short sale.

The other offered him “a Trial Period Plan.” This variety of modification would again increase his monthly payment, to $1,688. Making three straight payments would qualify Mr. Mudd for a permanent modification, though the bank hasn’t disclosed the exact terms.

He made one of the $1,688 payments in July, but didn’t make the August payment.

Mr. Mudd said a housing counselor has suggested that he walk away from the house and find an affordable rental in the area. He hasn’t. But, he said, “I am not sure it is worth the fight anymore.”