The Slow Rise And Quick Fall Of The SEC’s Enforcements

September 13, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated September 11, 2013, 8:46 p.m. ET

CRISIS PLUS FIVE

SEC Tries to Rebuild Its Reputation

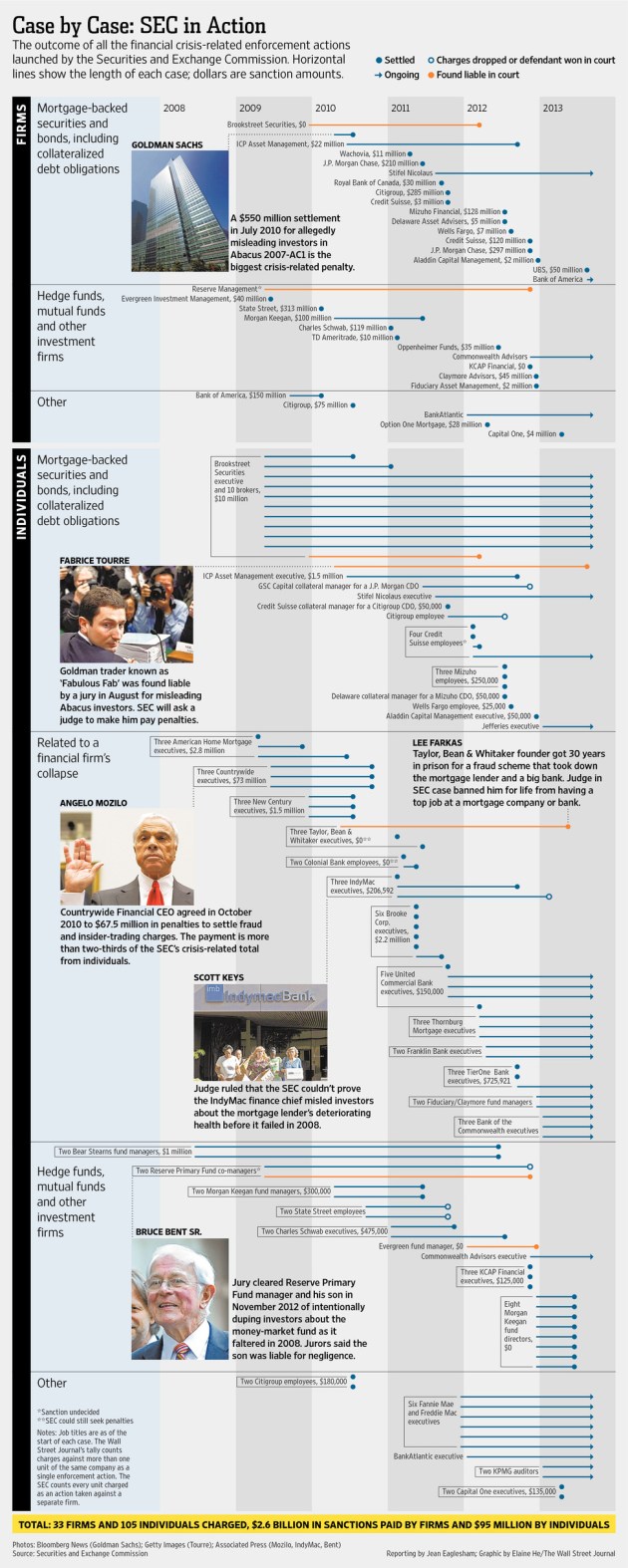

The Securities and Exchange Commission is ending its push to punish financial-crisis misconduct in the same way it started—with a new chairman vowing that Wall Street’s top cop will be tougher in the future. In 2009, at the depths of the recession,Mary Schapiro took the reins at the SEC promising to “move aggressively to reinvigorate enforcement” at the agency. She created teams to target various types of alleged misconduct, including one focused on the complicated mortgage bonds that helped set off a global financial panic.The agency has filed civil charges against 138 firms and individuals for alleged misconduct just before or during the crisis, according to an analysis by The Wall Street Journal. And it received $2.7 billion in fines, repayment of ill-gotten gains and other penalties. But some of the SEC’s highest-profile probes of top Wall Street executives have stalled and are being dropped.

n April, former federal prosecutor Mary Jo White started work as SEC chairman with a simple enforcement motto: “You have to be tough.” She tossed out the SEC enforcement policy that allowed almost all defendants to settle cases without admitting wrongdoing. In August, hedge-fund manager Philip Falconebecame the first example of this new approach when he and his firm, Harbinger Capital Partners LLC, admitted manipulating bond prices and improperly borrowing money from a fund. A representative of Mr. Falcone declined to comment.

The policy shift comes as the SEC turns the page on its financial crisis work. New investigations into misconduct linked to the meltdown have slowed to a trickle. And a statute-of-limitations deadline that generally restricts the sanctions the SEC can get for conduct more than five years old is looming for many cases.

The SEC’s crisis-related actions are producing diminishing financial returns. In 2010, the SEC filed enforcement actions against companies that brought average settlements of $212 million, the Journal analysis shows. Settlements from actions filed last year have averaged $61 million.

It is a similar story with settlements reached with individuals. The SEC has collected $95 million in such settlements since the crisis began, but more than two-thirds of this total came from the agency’s pact nearly three years ago with Angelo Mozilo. The Countrywide Financial Corp. founder agreed in 2010 to the payment of $67.5 million to settle allegations he misled investors and engaged in insider trading, without admitting or denying wrongdoing. A lawyer representing Mr. Mozilo didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“We’re at the outer end of credit-crisis cases,” SEC co-chief of enforcement George Canellos said this summer. Ms. White is mulling plans on how to use resources freed up by the rapid drop in those probes, according to people close to the agency.

Some critics say the SEC should have done far more in the past five years. There have been “almost no legal, political or economic consequences” for the big banks, says Phil Angelides, former chairman of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, a panel created by Congress to examine the causes of the crisis. “What has Wall Street really learned? Very little.”

Ms. Schapiro says the SEC shouldn’t be judged on the size of its settlements alone. “A fair scorecard looks at the importance and significance of the cases, as well as the numbers,” she said. “Broadly speaking, the SEC’s enforcement program does well on all those metrics.”

In 2009, Ms. Schapiro says she arrived at a demoralized SEC that was facing calls for its abolition, amid widespread criticisms of its effectiveness.

The agency’s failure to clamp down on the practices that led to the financial crisis wasn’t the only blemish. Officials missed signs of Bernard L. Madoff’s Ponzi scheme until the $17.5 billion fraud collapsed in late 2008.

Rebuilding the SEC’s reputation has been hard. In August 2009, a team of SEC lawyers came to a Manhattan courthouse expecting a federal judge to rubber stamp a settlement with Bank of America Corp., BAC -1.16% according to people close to the agency.

The case was the SEC’s first against a Wall Street firm related to the financial crisis and marked an important milestone in the agency’s efforts to bolster its standing.

The proposed deal followed a familiar blueprint by the regulator. Bank of America had agreed to write a $33 million check to settle allegations that investors were misled about bonuses paid to employees of Merrill Lynch & Co. shortly before Bank of America acquired it in January 2009. Bank of America didn’t admit or deny wrongdoing.

Enforcement officials at the agency saw the deal as evidence of their rapid and effective progress in tackling alleged crisis-related misconduct, according to a person familiar with the matter.

U.S. District Judge Jed S. Rakoff saw things differently. In September 2009, a year after the nadir of the financial crisis, he rejected the settlement, calling it “neither fair, nor reasonable nor adequate” and asked why shareholders were being punished, rather than bank executives. Five months later, the judge approved a revised pact with Bank of America to settle a wider set of allegations for $150 million, saying: “While better than nothing, this is half-baked justice at best.” Bank of America neither admitted nor denied these allegations.

The dressing down frustrated SEC enforcement officials, who believed the judge failed to appreciate their efforts to get the best deal possible, said the person familiar with the matter. Judge Rakoff declined to comment.

In early 2010, a new SEC leadership team of Ms. Schapiro and enforcement chief Robert Khuzami set about shaking up the agency’s enforcement division of more than 1,000 people. As well as new specialized enforcement units, the SEC brought in more Wall Street experts, created a new system to reward cooperation by enforcement targets and flattened out the division’s management structure.

Mr. Khuzami says the scale of the reforms gives the lie to critics who claim the SEC was content to let some of the biggest fish on Wall Street swim free, irrespective of their conduct.

“You don’t do all that [work on reforms] just to not bring cases,” Mr. Khuzami, who left the agency in January and recently joined law firm Kirkland & Ellis LLP as a partner.

He added that decisions to walk away from certain investigations without filing charges came down to the lack of proof of misconduct, not a lack of determination.

“All you can do is roll up your sleeves and look hard at the evidence and explore all possible theories—the case is either there or it’s not,” he said.

The SEC conducted an extensive investigation of Richard Fuld Jr., who ran Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. when the brokerage firm careened into bankruptcy in September 2008. But the agency has no plans to file charges against him, people close to the investigation said. A lawyer representing Mr. Fuld declined to comment.

The SEC in 2010 closed its probe into American International Group Inc. executive Joseph Cassano, who ran the unit that helped force the insurer’s bailout by taxpayers. A lawyer representing Mr. Cassano said the SEC “saw all the evidence and found no basis to sue Mr. Cassano, since his actions were wholly consistent with his responsibilities.”

The SEC’s biggest crisis-related corporate settlement came in 2010, when Goldman Sachs Group Inc. GS -1.04% agreed to pay $550 million to settle allegations it misled investors in a mortgage-bond deal. Goldman didn’t admit or deny wrongdoing in the pact, which remains the largest-ever penalty paid by a Wall Street firm to the SEC. A Goldman spokesman declined to comment.

Ms. Schapiro describes the Goldman deal as a “good example” of the way the SEC’s brought crisis-related cases “that change the way the industry does business.”

Ms. Schapiro managed to persuade lawmakers to increase the SEC’s budget and give the agency new powers in their 2010 Dodd-Frank financial overhaul law. The agency’s new ability to offer lucrative rewards for whistleblowers has helped several marquee investigations now under way, said Mr. Canellos, the SEC co-chief of enforcement. “There are a good number of cases that are going to involve awards to whistleblowers in the many millions of dollars each,” he said.

But Ms. Schapiro failed to get all she wanted. She told Congress that the SEC was prevented by law from basing the size of its fines on the scale of investor losses. Instead, the SEC had to look to factors such as allegedly illegal profits.

“I asked Congress for stronger powers to impose sanctions, including penalties related to the losses suffered by investors,” said Ms. Schapiro, now a managing director at consulting firm Promontory Financial Group LLC. Congress didn’t do it.

SEC officials say privately the agency gets unfairly blamed for the perceived enforcement failures of prosecutors. While the SEC has reached numerous settlements with Wall Street firms and their employees, the Justice Department has won criminal convictions in one crisis-related case involving an investment bank.

Mr. Khuzami in a speech in 2011 said he often got asked, “Why isn’t the SEC putting more people in jail?” The SEC has civil powers only and so can’t jail people. The Justice Department doesn’t keep a tally of its financial crisis prosecutions. During recent years, the Justice Department has won numerous convictions against Wall Street executives for insider trading unrelated to the financial crisis. A spokesman said, “The department has aggressively prosecuted a range of complex and sophisticated financial fraud cases, and a number of major investigations are still ongoing.”

In total, the SEC has filed crisis-related enforcement actions against 105 individuals, according to the Journal analysis. The agency has reached settlements with 59 of those people. Six crisis-related cases against individuals by the SEC were later dropped or rejected in court. The SEC has won cases against four individuals, excluding cases where civil charges were filed against a person also convicted of criminal charges.

The SEC hasn’t pursued enforcement actions against several prominent banks that concocted complex debt instruments that unraveled dramatically, dragging down the U.S. economy. The SEC aims to bring at least one more case involving collateralized debt obligations—investments based on cash-generating assets like mortgages that were pooled and sold in slices—before they wrap up their crisis enforcement work, according to people close to the agency.

“They’ve not had the big case that everybody wanted to see…a major player being held really accountable,” says Barbara Black, a law professor at the University of Cincinnati. She led a group of 19 securities-law experts who raised concerns last year about the SEC’s policy of allowing firms to settle cases without admitting wrongdoing.

But James Cox, a Duke University law professor who has studied the SEC for more than 30 years, says denunciations of the agency for failing to catch enough bad guys are unfair. “There’s a lot to be said for the SEC’s first line of defense, which is that it’s not unlawful for people to have unconscionable greed,” says Mr. Cox.