The Fed’s Commitment Issue; Surprise Decision to Hold Off on Scaling Back Bond Purchases Shows It Hadn’t Convinced Investors It Intends to Keep Short-Term Rates Low for Longer

September 20, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated September 18, 2013, 7:12 p.m. ET

The Fed’s Commitment Issue

Surprise Decision to Hold Off on Scaling Back Bond Purchases Shows It Hadn’t Convinced Investors It Intends to Keep Short-Term Rates Low for Longer

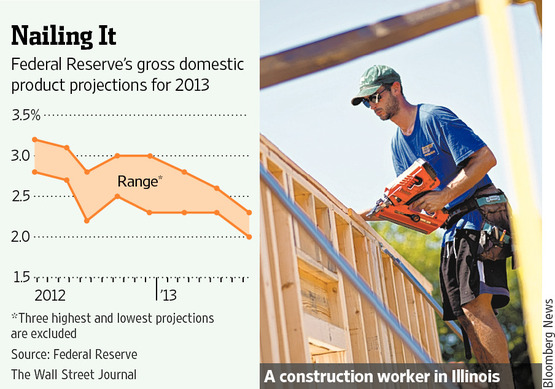

On second thought, maybe not. The Federal Reserve’s decision not to reduce monthly bond purchases got a rousing cheer from investors Wednesday. Stocks rallied, sending the Dow Jones Industrial Average to a new record, as did Treasurys, pushing yields sharply lower. The response was good news for the Fed—higher stock prices and lower long-term interest rates offer more support to an economy that remains in a rut. But it also could make for some headaches down the road.With the economy not nearly as strong as it expected, it isn’t hard to see why the Fed opted to hold back. In June, most Fed policy makers thought that gross domestic product would be 2.3% to 2.6% higher in the fourth quarter than a year earlier. Wednesday, it said that range slipped to 2% to 2.3%, which is still a bit optimistic compared with Wall Street economists’ forecasts.

Inflation remains low enough that a recession might easily tip it and the economy into deflation. The August jobs report was worryingly weak, while recent housing data, including Wednesday’s report on new-home construction started last month, have shown signs of softening.

A jump in interest rates may be one reason the economy hasn’t lived up to the Fed’s expectations. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note went from 2.01% in late May, when Mr. Bernanke first put the possibility of scaling back bond purchase on the table, to 2.85% on Tuesday. Wednesday, following the Fed’s decision, it fell to 2.71%. In its postmeeting statement, the Fed acknowledged that tighter financial conditions “could slow the pace of improvement in the economy and labor market.”

The rise in long-term interest rates came as a surprise to the Fed. Slowing down bond purchases would amount to “letting up a bit on the gas pedal as the car picks up speed, not applying the brakes,” said Mr. Bernanke in June. Moreover, research had suggested that the more powerful force in keeping long-term rates down wasn’t the bond purchases at all but the Fed’s commitment to keeping overnight rates near zero at least until the unemployment rate falls below 6.5%.

What Fed officials may not have recognized was how intertwined its bond-purchase program and its commitment not to raise short-term rates were in investors’ minds. Investors saw scaling back bond purchases as a prelude to raising short-term rates.

The Fed was unable to shake them of that belief. Wednesday, it threw in the towel.

In doing so, however, it only cemented the perception that the Fed’s bond purchases and its short-term rate commitment are closely allied. Ending the bond-buying program will be even harder now.

Updated September 18, 2013, 10:11 p.m. ET

Stock Investors Are Left Wondering When on Fed’s Taper

Stocks Welcomed the Fed Sticking to Its Policy, but Big Questions Remain

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve gave the markets uncertainty and confusion about plans to wind down its bond-buying program, and markets loved it, sending U.S. stock indexes to records.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 147.21 points, or 0.9%, to 15676.94, a closing high. Bond prices notched their strongest gain since November 2011. Commodity prices jumped, and foreign stocks benefited even more than U.S. shares. Early Thursday, Asian stock markets also moved higher.

The celebration was for the short term, based on the Fed’s decision to surprise investors with the news it wouldn’t begin reducing its bond-buying program this month after all.

But, in the longer term, money managers could turn surly again. If Fed officials are right in their decision to reduce forecasts for U.S. economic growth, some investors fear that could presage disappointments in third-quarter corporate profit reports, which are due out next month. That would be less positive for stocks.

And, more generally, analysts still expect the Fed to begin reducing stimulus at some point this year. That means that, as the next Fed policy meeting scheduled for Oct. 29-30 draws nearer, stocks could sink amid the same uncertainty and confusion that sent markets into a funk in August.

“In the longer term, the Fed is going to be less supportive” of financial markets, said Russ Koesterich, chief investment strategist at asset-management firm BlackRock Inc., which oversees about $3.9 trillion. “Strength will have to come from earnings growth.”

He and several other money managers said they are either moving some money into emerging-market stocks or, in accounts where clients make the final decisions, advising them to do so.

Markets generally trade on very short-term expectations, and the continuation of the Fed policy without any change is good short-term news for two reasons. First, it means stronger support than had been expected for the economy, which can’t hurt economic growth. Second, the stimulus itself is carried out in a way that funnels extra cash directly into markets, which, for simple mechanical reasons, tends to support stock and bond prices.

The Fed provides the stimulus by buying $85 billion a month worth of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, mainly from major banks. It is nearly impossible for the banks to use all that money for loans to businesses and individuals. With safe investments offering low returns, much of the money finds its way into the riskier stocks and bonds that investors think will get the best short-term pop.

Since the Fed uses the money to buy bonds, it would seem logical to expect bonds to get the greatest benefit. But because investors typically channel the liquidity into riskier, faster-rising investments, and because they still think the Fed will cut back on its bond purchases later in the year, analysts don’t expect bonds to benefit as much as stocks. Sooner or later, they think, investors will move away from Treasury bonds again, pushing bond prices lower and yields higher in anticipation of a cutback in Fed bond buying.

While short-term traders love the liquidity, some investors more focused on the longer term weren’t pleased. They worry that U.S. stocks in particular are becoming overpriced and too dependent on government support. When the Fed begins withdrawing that support, they say, the market reaction could be more negative than if the Fed had begun the process this month.

“U.S. stocks are trading based on stimulus and not on fundamental value,” said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer at BMO Private Bank, which oversees $66 billion in Chicago. “I was hoping that we would slowly get a transition from the liquidity backstop and toward a more tangible source of support, like corporate earnings or revenues.”

Mr. Ablin also said he fears the Fed is delaying action because it expects economic growth and corporate earnings could be disappointing in the months to come. He is thinking about moving some of his clients’ money into European and developing-country stocks.

“It is sort of disturbing to me as to why they chose to wait. Is the economy so fragile that it can’t sustain itself without life support?” he asked.

The Fed nudged down its 2013 and 2014 U.S. growth forecasts Wednesday.

Mr. Ablin noted that $45 billion of the monthly $85 billion in Fed bond purchases goes into Treasury bonds, meaning Fed purchases are financing most, if not all, of the federal budget deficit. He considers that unsustainable.

That kind of fretting was overshadowed Wednesday by optimism that the Fed’s continuing support will help the economy get through any rough patch that lies ahead.

“All in all, I guess it is fairly good,” said Janna Sampson, co-chief investment officer at OakBrook Investments, which manages $3.5 billion in Lisle, Ill.

Some investors also are reassured at the prospect that Lawrence Summers, a former senior adviser to Presidents Obama and Clinton, has withdrawn from consideration as a successor to Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke.

Mr. Summers was viewed as less supportive of the stimulus program than Janet Yellen, vice chairwoman of the Fed’s Board of Governors, who now is considered the strong favorite to succeed Mr. Bernanke when his term ends Jan. 31.

Many investors are hoping Ms. Yellen will go more slowly in ending stimulus than Mr. Summers might have, which means more short-term liquidity for the stock market.

The big question is what investors will do ahead of the Fed’s two remaining meetings this year, at the end of October and on Dec. 17 and 18. As the meetings approach, investors will again start debating how soon the Fed will cut stimulus.

Optimists think the Fed’s decision to delay any cutback this month will sow hope that it won’t act until the economy really is ready to absorb the blow. That would promote market stability. But pessimists worry that the Fed’s willingness to surprise investors will make investors even more nervous as future meetings approach. If so, markets could return to volatility like that seen earlier in the summer.

“They are going to have to do it at some point, and there is going to be pain when they do it,” said Ms. Sampson. Interest rates are likely to rise whenever investors anticipate a stimulus cutback, and higher rates are bad both for stocks and for bonds, at least in the short term.

Some investors worry that the uncertainty itself eventually will weigh on stocks.

Doug Cote, chief investment strategist for ING U.S. Investment Management, said this month’s surprise decision not to begin trimming stimulus has weakened the central bank’s credibility. “The Federal Reserve cannot lead the market to a decision and completely not do what [Mr. Bernanke] said he was going to do,” Mr. Cote said. “I am perplexed and baffled,” he said. “I do this for a living. I shouldn’t be so confused and confounded.”

UBS: The Fed Is Going To Regret What Happened Yesterday

MATTHEW BOESLER SEP. 19, 2013, 9:03 AM 6,085 17

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke is seen prior to the International Monetary and Financial Committee at the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank Group in Tokyo, October 13, 2012.

UBS economist Drew Matus says the Federal Reserve may regret passing up on a rare opportunity to reduce quantitative easing without unduly disrupting the market.

Yesterday, the FOMC (the Federal Reserve’s monetary policymaking body) decided to go against market expectations and refrain from announcing a reduction in the pace of monthly bond purchases it makes under quantitative easing.

The market reaction showed that a “tapering” of QE was largely priced in – stocks, bonds, and gold all soared while the dollar tanked.

And because the taper was already largely priced in – such that perhaps markets wouldn’t have sold off so strongly on the actual announcement of a taper – UBS economist Drew Matus writes in a note that “the FOMC may come to regret passing on this opportunity.”

“We would note that opportunities such as the one offered to the Fed today are rare: to date no central bank that has ever begun quantitative easing has been able to exit from those policies,” says Matus.

In the note, he writes (emphasis added):

A consequence of this inaction may be that the market will view future Fed communications with some scepticism. We have argued repeatedly that introducing some uncertainty into the Fed’s decision-making process could actually support the Fed’s goals. However, we viewed increasing the uncertainty with regard to the process, not to the goals themselves.

The Fed’s actions today reduce both the transparency the Fed has argued supports their goals AND the clarity of their goals, the latter being more significant as it could cause an unwelcome increase in volatility. This is likely to prove costly when the Fed finally does move to taper.

The bottom line, according to Matus: “In our view, particularly now that any Fed warnings regarding a taper are likely to be discounted by market participants, there are higher odds of a disruptive sell-off in equity markets in response to a taper announcement.”

September 18, 2013

Breathing Room for Emerging Markets Watching Money Flee

By KEITH BRADSHER, SIMON ROMERO and CEYLAN YEGINSU .

JAKARTA, Indonesia — When the Asian financial crisis hit in 1997, sales plummeted 95 percent and stayed down for six months at the IGP Group, Indonesia’s dominant manufacturer of car and truck axles. Four-fifths of the company’s workers lost their jobs.

When the global financial crisis began in 2008, IGP’s sales briefly dropped nearly one-third, and a quarter of the employees were put out of work.

The latest downturn, which began in early August, has been much more modest. IGP’s axle shipments are down 10 percent in the last month from a year ago. The company’s work force has barely shrunk, to 2,000 from 2,077 at the end of July, though IGP plans to reach 1,900 by the end of this year.

“These are challenging times, but I don’t think they will be the same as in 2008 or 1998,” Kusharijono, IGP’s operations director, who uses only one name, yelled over a clanking, cream-colored assembly line here for minivan rear axles.

From Indonesia and India to Turkey and Brazil, capital flight from developing economies to the United States is already causing hardship for millions of businesses and workers. More was expected if the Federal Reserve decided to retreat from its economic stimulus campaign of buying billions of dollars in bonds each month.

That it decided on Wednesday not to stop may relieve some companies, government leaders and economists who worried that rising interest rates in the United States would draw tens of billions of dollars out of emerging markets and cause local currencies to fall further against the dollar.

Investors have been moving money into dollar-based investments that offer higher yields.

But the Fed’s announcement Wednesday afternoon took currency traders by surprise, and the dollar plunged against major currencies. The dollar fell a little more than 1 percent against the euro and the yen after the announcement, giving companies in the developing economies a little more breathing room. On Thursday, currencies in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia, which have fallen sharply in recent months, headed higher, with the Indonesian rupiah gaining about 1.5 percent against the dollar by late morning in Asia.

The economic slowdowns in the developing economies seem less severe so far than in other recent downturns. While previous exoduses by investors from volatile emerging markets have caused waves of bank failures, corporate bankruptcies and mass layoffs, the latest retrenchment has been much milder so far. That partly reflects the belief that when the Fed does move, it will scale back its bond purchases very gradually, business leaders and economists around the world said in interviews this week. The effects have also been limited partly because banks, companies and their regulators in many emerging markets have become much more careful about borrowing in dollars over the last two decades, except when they expect dollar revenue with which to repay these debts.

In 1997 and 1998, “the whole problem began with the banking sector. Now I think the banking sector is much better,” said Sofjan Wanandi, a tycoon who is the chairman of the Indonesian Employers’ Association and part owner of IGP.

Trading in currency and stock markets seems to suggest that some of the worst fears over the summer are starting to recede. The Brazilian real has recovered about 8 percent of its value against the dollar since Aug. 21 and a little over a third of its losses since the start of May, when worries began to spread about the vulnerability of emerging markets to a tightening of monetary policy. Stock markets from India to South Africa have rallied from lows in late August, with Johannesburg’s market up 14.7 percent since late June after a swoon earlier than most emerging markets.

“While the Fed hasn’t started the tapering process as yet, there has been a considerable withdrawal of money in the emerging markets and especially in India since May. In my opinion, the major effect has already taken place,” said Sujan Hajra, the chief economist at AnandRathi, an investment bank based in Mumbai.

One lingering question is how much inflation will accelerate in emerging markets. Many of their industries depend heavily on commodities like oil that are priced in dollars.

Weakening exchange rates this year for almost every emerging market’s currency have made these dollar-denominated commodities more expensive. That is starting to drive up inflation in a few countries that do not subsidize fuel prices, and it is adding to government deficits in many countries, like India and Indonesia, that do.

In Brazil, an increase in transportation fares set off street protests in June, leading to broad demonstrations over corruption and lamentable public services. Salomão Quadros, an economist at Fundação Getulio Vargas, a top Brazilian university, said inflation was expected to reach about 6 percent this year as imported goods become more expensive.

While that level exceeds the central bank’s inflation target of 4.5 percent, inflation in Brazil still remains much lower than it has been in other stretches of market turbulence, as in 2003, when inflation rose to about 15 percent. “Brazil is facing some difficulties, but we’re not in crisis territory,” Mr. Quadros said.

The most vulnerable companies are those that mostly sell domestically in their local currency but have debts or costs denominated heavily in dollars. One example is the plastics industry, which often relies on imported resins made to a large extent from high-priced oil.

Ahmet Nalincioglu, the managing director of Elektroplasmin, a plastic packaging company based in Istanbul, said many plastics producers would have to try to raise prices. Yet Elektroplasmin has yearlong contracts with clients that are hard to change.

“Our price hikes will automatically have a negative impact on their profit margins, which means they will be reluctant to negotiate,” Mr. Nalincioglu said. “If I can’t agree on a price, I get stuck with the stock for a year and suffer huge losses.”

The most vulnerable countries are those running large trade deficits they have been financing with dollars from overseas investors’ purchases of local assets like real estate, stocks and bonds. India is conspicuous on that list, as its poor roads and stifling bureaucracy have discouraged exports and resulted in its luring few of the factories now moving out of China in response to surging wages there.

A few emerging markets, still traumatized by the extent of their economic downturns during previous periods of capital flight, are taking drastic action to stabilize their currencies. Indonesia had one of the few emerging market currencies that was still falling through last week, but the central bank stopped the drop last Thursday when it unexpectedly raised its two benchmark interest rates by a quarter percent.

The interest rate increase made it more attractive for international investors to lend money to Indonesia, but at the risk of further weakening a domestic economy that is already decelerating.

Didik Rachbini, one of the 21 members of the presidential National Economic Council here, said the Indonesian government was also discussing delays in big investment projects by state-owned enterprises, to conserve foreign exchange. Work like road construction that requires few imports of equipment is likely to proceed, while capital-intensive projects that rely on foreign technology should face extra scrutiny and are starting to be reviewed, he said.

Most affected by the economic slowdown are workers in developing countries who were already scrimping. Hasan Qodri, a 22-year-old axle quality inspector at Indonesia’s IGP, said he regretted the disappearance of overtime — and the extra pay that went with it.

“Of course I would like more overtime,” he said, “so I’d have more money for my daily life.”

Bernanke Saves Companies $700 Billion as Apple to Verizon Borrow

America’s companies, from Apple Inc. (AAPL) to Verizon Communications Inc., are saving about $700 billion in interest payments with the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented stimulus.

Corporate bond yields over the past four years have fallen to an average of 4.6 percent from 6.14 percent in the five years before Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.’s demise, a savings equal to $15.4 million annually per every $1 billion borrowed. Businesses took advantage of the Fed’s largesse to lock in record low rates, extend maturities and raise cash by selling $5.16 trillion of bonds, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“The stimulus was a huge saving grace in the economy overall,” said J. Michael Schlotman, the chief financial officer at Cincinnati-based Kroger Co. (KR), the grocery store operator that estimates it’s paying about $80 million less in interest than it would have pre-crisis. “It probably kept some businesses from failing because they were able to refinance their debt at lower interest payments.”

The combination of a near-zero rate policy and more than $3 trillion of bond purchases by the Fed since December 2008 means that the collective interest savings enjoyed by Apple, Verizon (VZ) and more than 2,000 other corporate borrowers exceeds Switzerland’s $632 billion economy.

Defaults Plummet

That’s money freed up to expand businesses and hire workers. Corporations boosted their capital expenditures to $699 billion in the three months ended June 30, about the most in a decade, and up 8.7 percent from the corresponding period last year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. Even the neediest companies have been able to obtain cash as the trailing 12-month U.S. speculative-grade default rate has plummeted to less than 3 percent from more than 13 percent back in 2009.

Drugstore chain Rite Aid Corp. (RAD) and residential property firm Realogy Corp. (RLGY) are two of the 283 junk-rated borrowers identified in March 2009 by Moody’s Investors Service as being at the highest risk of default that have since sold bonds.

After plunging to 9.5 cents on the dollar in March 2009, Camp Hill, Pennsylvania-based Rite Aid’s $295 million of debentures due February 2027 have rebounded to 101.38 cents, as their yields fell to 7.53 percent from 80 percent.

While borrowing costs are starting to rise in anticipation that the Fed will say as soon as today it will start reducing stimulus measures, they’re still below pre-crisis levels and enticing borrowers. Verizon sold $49 billion of bonds last week in the biggest corporate offering on record.

Quantitative Easing

When Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke started to pump cash directly into the financial system in December 2008 by purchasing bonds in a policy known as quantitative easing, unemployment was the highest in 26 years and companies rated below Baa3 at Moody’s and less than BBB- by Standard & Poor’s faced $1.2 trillion of debt maturing through 2015. That’s been cut to about $115.8 billion, according to Barclays Plc.

“The benefits of quantitative easing include the confidence that it gave to markets, which allowed credit markets to re-open,” said Eric Gross, a Barclays credit strategist in New York. “If a company can get to the primary market and pay off its obligations, it can live to fight another day. The problem back then was the primary market was completely closed.”

Companies sold just $21.9 billion of investment-grade and high-yield bonds in the month after Lehman collapsed on Sept. 15, 2008, less than half the size of Verizon’s sale last week.

Spending, Jobs

Kroger’s $3.1 billion of bond sales in the past four years included $600 million of 10-year notes sold in July with a 3.85 percent coupon. That’s below the 6.4 percent for similar-maturity debt that the largest supermarket operator in the U.S. issued in August 2007, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Schlotman said the interest savings gave him the confidence to ask Kroger’s directors to approve $10 billion in capital expenditures and boost employment by 35,000 jobs over the past five years. The company had 343,000 employees as of Feb. 2, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Savings of about $700 billion represents the difference between what companies that have sold bonds since Sept. 17, 2009, are paying annually based on an average maturity of nine years for securities in the Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. Corporate & High Yield Index, versus what they might have paid before the crisis.

IBM’s Record

After rising as high as 11.1 percent on Oct. 28, 2008, it wasn’t until Sept. 17, 2009 that yields fell below the pre-Lehman average of 6.14 percent, the Bank of America Merrill Lynch index shows.

International Business Machines Corp. (IBM), the largest computer-services provider, sold $1.25 billion of seven-year notes in May at a record low coupon of 1.625 percent. That compares with a 5.7 percent rate on 10-year debt issued in 2007 by the Armonk, New York-based company.

Verizon, the largest U.S. telephone carrier after No. 1 AT&T Inc., issued $49 billion of bonds in eight parts on Sept. 11 in the biggest sale on record to help fund its $130 billion purchase of the rest of Verizon Wireless from Vodafone Group Plc. On the $11 billion portion due in 10 years, the New York-based company is paying a coupon of 5.15 percent, less than the 5.5 percent on similar-maturity notes it sold in March 2007.

Verizon’s offering exceeded the previous record of $17 billion set on April 30 by Cupertino, California-based Apple. That sale, the iPhone-maker’s first since 1996, included $4 billion of 1 percent, five-year notes and $5.5 billion of 2.4 percent, 10-year securities.

Fed Taper

With the economy now firming, the Fed may say as soon as today that it will curtail its stimulus. Policy makers will likely reduce monthly purchases of Treasuries (USGG10YR) to $40 billion from $45 billion, according to a Bloomberg News survey of economists. They will maintain mortgage-bond buying at $40 billion, the survey showed.

Yields on 10-year Treasuries, a benchmark for everything from corporate bonds to mortgages, have risen to 2.85 percent from 1.76 percent on Dec. 31. Apple’s 2.4 percent bonds have fallen 11.3 cents since they were issued to 88.6 cents on the dollar, pushing the yield up to 3.83 percent.

The Fed embarked on its stimulus in the face of an economy spiraling into the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, when a collapse in the subprime mortgage market and deteriorating property values led to the forced sale of Bear Stearns Cos. and the demise of Lehman.

Early Benefits

Mortgage financiers Fannie Mae (FNMA) and Freddie Mac (FMCC) were placed into government conservatorship, insurer American International Group Inc. agreed to a U.S. takeover to avert collapse, Merrill Lynch & Co. was compelled to sell itself to Bank of America Corp. and automaker General Motors Corp. faced insolvency.

To bring down a jobless rate that eventually reached a peak of 10 percent in October 2009, the Fed cut its target rate for overnight loans between banks to a range of zero and 0.25 percent and started buying Treasuries and mortgage debt on Dec. 5, 2008.

Within the first 30 days of the program’s onset, yields on dollar-denominated corporate bonds dropped a percentage point to 9.8 percent on Jan. 5, 2009, Bank of America Merrill Lynch index data show. By the time the Fed started its second round of QE on Nov. 12, 2010, yields on the notes had plunged to 4.6 percent, less than half what they were two years earlier.

Interest Lowered

“It’s allowed companies such as ourselves to continue to access the capital markets,” Dan D’Arrigo, the executive vice president and chief financial officer of Las Vegas-based casino company MGM Resorts International (MGM), said in a Sept. 17 telephone interview. During the crisis, “we still had access but at much more costly rates to our company,” he said.

MGM, which runs the Bellagio and MGM Grand casinos, was able to lower its interest expenses by $230 million in December, to about $770 million annually, refinancing debt with $4 billion of loans and $1.25 billion of bonds, according to a Dec. 20 statement from the company.

As credit loosened, corporate yields plunged as low as 3.35 percent on May 2, from 9.76 percent at the end of 2008. Verizon has led $1.1 trillion of dollar-denominated issuance this year, on pace to surpass last year’s record $1.47 trillion, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Refinancings have cut the amount of speculative-grade bonds and loans set to mature in 2014 to $43.7 billion, compared with $331.5 billion when the Fed started its QE program in 2008.

‘Maturity Wall’

“There was this maturity wall that people were terrified of,” said Neil Wessan, the group head of New York-based CIT Group Inc. (CIT)’s capital markets unit. “That’s been spread out over a much broader period of time.”

CIT emerged from a month of bankruptcy protection in December 2009. After a $592.3 million loss last year, analysts surveyed by Bloomberg forecast CIT will report its highest earnings in 2013 and 2014 since exiting bankruptcy.

The business lender sold 5 percent securities in July that are due in August 2023 to yield 5.125 percent. That’s below the 6.625 percent coupon on seven-year notes it issued in March 2011, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“The availability of all this excess liquidity has allowed the market to re-price, amend and extend,” Wessan said. “That took a lot of pressure out of the system.”

Fed Governor Jeremy Stein warned in February that some credit markets, such as corporate debt, were showing signs of excessive risk-taking. Investors poured $758.7 billion into U.S. bond funds in the four years after 2008, according to research firm EPFR Global in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Stein’s Warning

“We are seeing a fairly significant pattern of reaching-for-yield behavior emerging in corporate credit,” Stein said at the time in a speech in St. Louis.

Company debt loads in the U.S. have increased faster than cash flow for six straight quarters. Debt of investment-grade companies rose in the second quarter to 2.09 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, according to JPMorgan. That’s up from 2.07 times in the first three months of 2013 and compares with 2.13 in the third quarter of 2009, when it peaked after the longest recession since the 1930s.

Rite Aid, which lost money in five of the past six years, sold $810 million of eight-year debentures in June paying 2.5 percentage points less than similar-maturity debt it issued last year.

The most indebted U.S. drugstore generated $504 million of free cash in the 12 months ended March 2, the most since at least 1996. Rite-Aid, which Moody’s placed on its “Bottom Rung” list in its March 2009 report, is ranked B3 by the ratings firm and B- by S&P, both six levels below investment grade.

Susan Henderson, a spokeswoman for Rite Aid, didn’t respond to a telephone and e-mail message seeking comment.

Realogy Cuts

Madison, New Jersey-based Realogy, the most indebted U.S. real-estate services company, has decreased its total interest expense to $255 million from $672 million in 2012, Chief Financial Officer Anthony Hull said in a July interview.

A strengthening economy may help indebted companies meeting interest payments even with yields on the Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. Corporate & High Yield index having risen to 4.23 percent, 0.64 percentage point more than at the end of 2012.

Gross domestic product is expected to grow by 2.65 percent next year from 1.6 percent this year and after contracting 2.8 percent in 2009, according to 81 economists surveyed by Bloomberg. The unemployment rate was 7.3 percent in August.

The Fed’s QE “was the right thing at the right time,” Kroger’s Schlotman said. “You can’t keep rates here forever. At some point, market forces have to drive your ability to succeed in the marketplace.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Lisa Abramowicz in New York at labramowicz@bloomberg.net

Fall in Home Loans Pushing Fed Away From Taper in Mortgage Bonds

By Jeff Kearns – Sep 18, 2013

Federal Reserve policy makers, while considering today whether to taper $85 billion in monthly bond buying, confront a drop in demand for home loans that argues against a cut to their mortgage bond purchases.

A surge in mortgage rates to two-year highs has undercut borrowing, pushing down refinancing by more than 70 percent since last September. Wells Fargo & Co. (WFC) said this month originations may fall 29 percent this quarter, while JPMorgan Chase & Co. said volumes may plunge 40 percent in the second half compared with the first six months of the year.

The Fed today would limit the impact from tapering by reducing Treasury purchases rather than mortgage-backed securities, said Michael Gapen, a senior U.S. economist at Barclays Plc in New York. Buying mortgage bonds reduces home loan rates, increases house prices, and pushes up consumer confidence and spending, said Gapen, a former researcher in the Fed’s Division of Monetary Affairs.

“There’s a fair degree of consensus that MBS purchases are more effective than Treasuries in terms of stimulating activity,” said Gapen, who expects the Fed to reduce monthly purchases by $10 billion in Treasuries and $5 billion in mortgage bonds. “It’s a more direct route to housing and household balance sheets.”

The Federal Open Market Committee today will probably conclude a two-day meeting by dialing down monthly Treasury purchases by $5 billion to $40 billion, while maintaining its buying of mortgage-backed securities at $40 billion, according to a Bloomberg News survey of economists. The FOMC has pledged for more than a year to press on with bond buying until achieving substantial labor market gains.

“More Effective”

“Fed leadership probably views MBS purchases as more effective in boosting economic activity than Treasury purchases,” Jan Hatzius, the New York-based chief economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., said in a Sept. 13 note to clients, referring to mortgage-backed securities. The central bank will probably curtail its monthly buying of Treasuries by $10 billion and not alter its level for mortgage bond purchases, he said.

Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and his policy making colleagues are debating how to scale back unprecedented stimulus aimed at stoking economic growth and reducing unemployment that was 7.3 percent in August. The Fed has held the main interest rate near zero since December 2008 and pushed its balance sheet to a record $3.66 trillion through three rounds of bond buying.

Fed officials such as Kansas City Fed President Esther George, who has voted on the FOMC this year against expanding stimulus, say balance sheet growth risks creating asset price bubbles and unmooring inflation expectations. George called this month for trimming monthly buying to about $70 billion.

First Round

In the first round of so-called quantitative easing starting in 2008, the central bank bought $1.25 trillion of mortgage-backed securities, $175 billion of federal agency debt and $300 billion of Treasuries. In the second round, announced in November 2010, the Fed bought $600 billion of Treasuries.

The FOMC began its current program in September 2012 with purchases of mortgage bonds, adding Treasuries in December.

Bernanke said in an August 2012 speech the first two rounds of quantitative easing provided “significant help to the economy” by boosting stocks and pushing down yields on mortgage-backed securities and government and corporate bonds.

The initial buying plan may have cut the yield on 10-year Treasury notes by between 0.4 percentage point and 1.1 percentage point, while the second program may have reduced the yield by between 0.15 percentage point and 0.45 percentage point, Bernanke said in the speech at Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

The two buying rounds “may have raised the level of output by almost 3 percent and increased private payroll employment by more than 2 million jobs,” he said.

Bigger Payoff

The central bank gets a bigger payoff from buying mortgage-backed securities — so-called MBS — compared with Treasuries, said Arvind Krishnamurthy, a finance professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

“MBS purchases have more bang for the buck,” said Krishnamurthy, a former adviser to the Fed Board of Governors and the Fed district banks of New York and Chicago. “If the Fed was to decide that they want to reduce the size of their balance sheet but in a way that has less cost in terms of the stimulus that they’re providing, then it would follow that the appropriate strategy is to taper more on the Treasury side.”

Demand Declines

Demand for mortgages has fallen as the average rate on a 30-year mortgage rose to 4.57 percent in the week ended Sept. 12 compared with a record-low 3.31 percent in November, according to Freddie Mac.

Home loan applications dropped 13.5 percent in the week ended Sept. 6 to the lowest level since October 2008, according to theMortgage Bankers Association. Refinancing fell 20.2 percent to the weakest level since June 2009.

Purchases of new U.S. homes plunged 13.4 percent in July, the most in more than three years, with sales falling to a 394,000 annualized pace, according to the Commerce Department.

The biggest U.S. banks say the decline in loan demand may exceed expectations. San Francisco-based Wells Fargo, the top U.S. home lender, is cutting 2,300 jobs in mortgage production, while Bank of America Corp., based in Charlotte, North Carolina, has cut 2,100 positions.

Still, homebuilder confidence held in September at the highest level in almost eight years. The National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo confidence index registered 58 this month, matching August’s revised reading as the strongest since November 2005, according to a report yesterday from the Washington-based group.

Index Surged

Such optimism has found fuel from a recovery in home prices that pushed up the S&P/Case-Shiller (SPCS20Y%) index of values in 20 cities by 12.1 percent in June from a year earlier. The index surged 12.2 percent in the year ended in May, which was the biggest gain since March 2006.

“Housing has legs,” said John Silvia, chief economist at Wells Fargo in Charlotte, North Carolina. “But the overall sense in the U.S. is that it’s still not up to snuff, and I believe the Fed will want to stay away from the MBS and say, ‘Let’s just taper the Treasuries.’”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeff Kearns in Washington at jkearns3@bloomberg.net

Fed delay both delights, confounds investors

7:52pm EDT

By Steven C. Johnson

NEW YORK (Reuters) – Wall Street’s knee-jerk reaction to the Federal Reserve choosing to keep the pedal to the monetary policy metal was loud and clear on Wednesday: Buy Buy Buy!

That initial exuberance, however, masks a nagging worry and no shortage of confusion about the Fed’s reluctance to act after the central bank had positioned markets for a reduction in its $85 billion per month bond buying program. It left many investors in a fog about what comes next.

The trading day certainly did not unfold as expected. The vast majority of investors were bracing for a modest reduction in the Fed’s monthly purchases of U.S. Treasury debt and mortgage bonds.

But citing concerns about low inflation, the impact of a recent rise in long-term interest rates on housing, and headwinds from Washington’s “fiscal retrenchment,” the Fed said it needed to see more economic improvement before acting.

The Fed’s refusal to start to bow out of the asset-buying game sent stocks soaring, with the benchmark U.S. S&P 500 index closing at a record high.

“The Fed is sending a message that the economy is weak, and that’s confusing,” said Wayne Kaufman, chief market analyst at Rockwell Securities. “I would’ve been happier if there had been a small taper to prepare the investing public to the idea.”

Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke first suggested in May that the central bank could pull back on its bond purchases late this year if economic growth continued to gain traction, as he predicted it would in the second half of this year and in 2014.

That caught markets flat-footed in the spring and pushed up bond yields and mortgage rates by more than a percentage point over three months, slowing momentum in the U.S. housing market recovery.

The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, which began May trading as low as 1.61 percent, hit a two-year high this month just above 3.0 percent, before falling back to 2.69 percent on Wednesday.

That “tightening of financial conditions” over the summer could, if sustained, slow improvement in the economy and the labor market, the Fed said on Wednesday.

It likely influenced policymakers’ decision to cut their 2013 growth forecast to 2.0 percent to 2.3 percent from a June estimate of 2.3 percent to 2.6 percent, the biggest drop in the near-term forecast in more than a year. Some on the Fed’s policy committee thought 2013 growth could be as low as 1.8 percent.

The Fed is clearly telling markets that “the economy isn’t as strong as we’d like,” said David Joy, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial, “which has implications for corporate earnings down the road.”

MIXED MESSAGES

Economists polled by Reuters recently forecast the economy would grow at a 2.5 percent rate this year and 3.0 percent by the end of 2014.

That helps explain why investors erroneously bet on the Fed to begin “tapering” its bond purchases this month, said Douglas Borthwick, managing director at Chapdelaine Foreign Exchange. He was among the minority who thought the Fed would wait.

“The Fed has always said they were data-dependent. But the data over the past month hasn’t been good,” he said.

“We have yet to see the U.S. economy move at a pace that would let the Fed take the crutches away,” he added. “Crutches won’t fix a broken leg but they do help you to walk, and right now, (the bond purchases) are still the economy’s crutches.”

That’s not terribly comforting for bond investors who took the Fed’s cue and bet on a tapering this month.

Mary Beth Fisher, head of U.S. interest rate strategy at Societe Generale, took particular issue with the reference to tighter financial conditions hurting economic growth.

“Um, really? Multiple FOMC members have been preaching for months that tapering is not tightening, right? It’s simply a reduction of extraordinary accommodation,” she wrote in a note to clients.

With Fed Vice Chairman Janet Yellen seen as the front-runner to replace chairman Bernanke if he steps down as expected early next year, she said markets are confused about who is calling the shots.

“Where do we go from here,” she asked. “To the bar for a gin and tonic, and a long, slow consideration of just how dovish this new Federal Open Market Committee will be given the torch passing that appears to have occurred at this meeting.”

Jeffrey Gundlach, chief executive at DoubleLine Capital in Los Angeles, said the Fed has only itself to blame for prematurely signaling a pullback and sparking a worrisome rise in rates.

“The Fed botched its message in June and is trying to undo that mistake. The data does not suggest that the economy can make it on its own,” he said, adding that once the Fed begins tapering purchases, reversing course becomes tricky.

FISCAL FOLLIES

To be fair, some pointed out that Congress has made life difficult for the Fed by hitting the economy with government spending cuts and higher taxes earlier this year.

Now, the prospect of a government shutdown next month if Congress can’t agree on a new budget and a rise in the debt ceiling in coming weeks is raising new concerns.

In a news conference after Wednesday’s announcement, Bernanke said failure to raise the debt ceiling or keep the government open “could have very serious consequences for the financial markets and for the economy, and the Federal Reserve’s policy is to do whatever we can to keep the economy on course.”

“I think the Fed is very concerned about the potential for political dysfunction and to start withdrawing stimulus now might be to put something back in the bag that they may need in literally a couple of weeks,” said Brad McMillan, chief investment officer at Commonwealth Financial in Waltham, Massachusetts.

And that leaves investors wrestling with whether to be happy or worried.

On one hand, “people are going to say, ‘Hey, great, the Fed is back in the game, they’ve still got our backs,'” said McMillan. But “from a real economy standpoint, what (this decision) says is the Fed is more nervous about the economy than generally perceived.”

September 19, 2013 9:25 am

Fed inaction gives emerging economies breathing space

By Josh Noble in Hong Kong, James Crabtree in Mumbai and Daniel Dombey in Istanbul

After whispers of a brewing financial crisis, emerging markets greeted news that the US Federal Reserve would not start tapering its asset purchase programme with an overwhelming wave of euphoria. Equities, bonds and currencies rallied sharply on Thursday.

Mehmet Simsek, Turkey’s finance minister, described the Fed’s decision as“maintaining the status quo” in a tweet, adding it was “good news for emerging markets”.

Turkish stocks rallied more than 7 per cent, helping push the FTSE Emerging Markets index to its highest since the end of May. Borrowing costs fell further on Thursday as bonds extended their rally after the biggest one-day gain in almost three months on Wednesday.

Developing countries rushed to take advantage of the boost, announcing a flurry of bond deals as even bearish analysts threw in the towel and advised clients to embrace the euphoria. “From now on, we believe that a multi-week rally can develop in the period ahead, across all asset classes,” Benoit Anne of Société Générale said in a note.

Nonetheless, while the immediate dangers posed by the anticipated withdrawal of the Fed punchbowl have abated, analysts and money managers stressed that the failure to begin tapering this month merely provides breathing space to tackle underlying economic problems.

“What I think that the tapering – or non-tapering – decision does is essentially lengthen that window of opportunity where policy makers can apply the structural reforms to reassure investors for the long term,” says says Fred Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC. “So it buys us time, but it does not solve anything fundamentally.”

Several asset managers echoed this cautious note. Dominic Ross, chief investment officer for equities at Fidelity argued developed markets should benefit more than emerging ones. “Structural issues remain in the latter that show no signs of going away,” he says.

Many emerging economies have suffered large outflows of capital since late May, when the prospect of Fed tapering first emerged. Downward pressure on currencies, most notably the Indian rupee, the Indonesian rupiah and the Turkish lira, raised concerns that some countries dependent on overseas capital to fund persistent deficits could even face a balance of payments crisis.

Elsewhere, worries have focused on a rapid increase in consumer credit. Take Thailand and Malaysia, where household debt has risen to around 80 per cent of gross domestic product, from between 55-65 per cent in 2008. Some analysts fear that higher borrowing costs caused by tighter global monetary conditions would prompt a surge in bad loans.

“We’re on the wrong path. To get off that path we need to stop relying on excessive credit growth,” says Duncan Wooldridge, chief Asia economist at UBS. “We’ve got respite on the tapering story, but the cat is out of the bag for some of those countries with liquidity risk.”

Still, the Fed’s decision at least allows embattled policymakers in emerging economies some more time to push through reforms to prepare for the eventual tightening of US monetary policy.

The brief reprieve may be most welcome in India, where the new central bank governor Raghuram Rajan must contemplate a delicate first interest rate decision on Friday.

Mr Rajan is not expected to cut rates, but is now likely to face calls to reverse some of the steps taken by the Reserve Bank of India to drain liquidity in recent months, as part of a series of measures to bolster the currency. The rupee rose 2.6 per cent by later afternoon in London.

“India has got a get-out-of-jail-free card from the Fed. The question now is whether and how they will use that card,” says Sanjeev Prasad, head of research at brokerage Kotak Institutional Equities.

Even after factoring in Thursday’s spikes, both the Indian and Indonesian currencies have lost more than 11 per cent against the US dollar since May, while both central banks have spent billions of dollars on propping up the currencies, rapidly eroding their foreign exchange reserves. Brazil has bolstered the real by unveiling a $60bn intervention programme, but fund managers remain concerned over the country’s deteriorating fundamentals.

And the Fed’s largesse will not last forever. Barclays now forecasts a $15bn reduction in asset purchases by the US central bank in December, while Société Générale analysts say the move could be twice as large.

“”This rally is just far too much,” argues Michael Riddell, a bond fund manager at M&G Investments. “The market has gone from expecting rate hikes to pricing in quantitative easing forever. But fundamentally nothing has changed.”

Marc Faber Warns “The Endgame Is A Total Collapse – But From A Higher Diving Board Now”

Tyler Durden on 09/18/2013 19:31 -0400

With rumors this evening of the White House calling around for support for Yellen, Marc Faber’s comments today during a Bloomberg TV interview are even more prescient. Fearing that Janet Yellen “would make Bernanke look like a hawk,” Faber explains that he is not entirely surprised by today’s no-taper news since he believes we are now in QE-unlimited and the people at the Fed “never worked a single-day in the business of ordinary people,” adding that “they don’t understand that if you print money, it benefits basically a handful of people.” Following today’s action, Faber is waiting to seeing if there is any follow-through but notes that “Feds have already lost control of the bond market. The question is when will it lose control of the stock market.” The Fed, he warns, has boxed themselves in and “the endgame is a total collapse, but from a higher diving board.”

Faber on the reaction that there’s going to be no taper for now:

“My view was that they would taper by about $10 billion to $15 billion, but I’m not surprised that they don’t do it for the simple reason that I think we are in QE unlimited. The people at the Fed are professors, academics. They never worked a single life in the business of ordinary people. And they don’t understand that if you print money, it benefits basically a handful of people maybe–not even 5% of the population, 3% of the population. And when you look today at the market action, ok, stocks are up 1%. Silver is up more than 6%, gold up more than 4%, copper 2.9%, crude oil 2.68%, and so forth. Crude oil, gasoline are things people need, ordinary people buy everyday. Thank you very much, the Fed boosts these items that people need to go to their work, to heat their homes, and so forth and at the same time, asset prices go up, but the majority of people do not own stocks. Only 11% of Americans own directly shares.”

On whether interest rates are held down when the Fed continues this type of policy:

“On September 14, 2012, when the Fed announced QE3, that was then extended into QE4, and now basically QE unlimited, the bond markets had peaked out. Interest rates had bottomed out on July 25, 2012–a year ago–at 1.43% on the 10-year Treasury note. Mr. Bernanke said at that time at a press conference, the objective of the Fed is to lower interest rates. Since then, they have doubled. Thank you very much. Great success.”

On what the endgame is:

“Well, the endgame is a total collapse, but from a higher diving board. The Fed will continue to print and if the stock market goes down 10%, they will print even more. And they don’t know anything else to do. And quite frankly, they have boxed themselves into a corner where they are now kind of desperate.”

On Janet Yellen:

“She will make Mr. Bernanke look like a hawk. She, in 2010, said if could vote for negative interest rates, in other words, you would have a deposit with the bank of $100,000 at the beginning of the year and at the end, you would only get $95,000 back, that she would be voting for that. And that basically her view will be to keep interest rates in real terms, in other words, inflation-adjusted. And don’t believe a minute the inflation figures published by the bureau of labor statistics. You live in New York. You should know very well how much costs of living are increasing every day. Now, the consequences of these monetary policies and artificially low interest rates is of course that the government becomes bigger and bigger and you have less and less freedom and you have people like Mr. De Blasio, who comes in and says let’s tax people who have high incomes more. And, of course, immediately, because in a democracy, there are more poor people than rich people, they all applaud and vote for him. That is the consequence.”

On where he sees gold heading:

“When I look at the market action today, I would like to see the next few days, because it may be a one-day event. The markets are overbought. The Feds have already lost control of the bond market. The question is when will it lose control of the stock market. So, I’m a little bit apprehensive. I would like to wait a few days to see how the markets react after the initial reaction.”

On whether the 10-year yield will float back up to where it was before 2pm today:

“I will confess to you, longer-term, I am of course, negative about government bonds and i think that yields will go up and that eventually there will be sovereign default. But in the last few days, when yields went to 2.9% and 3% on the 10-year for the first time in years i bought some treasuries because I have the view that they overshot and that they could ease down to around 2.2% to 2.5% because the economy is much weaker than people think…I think in the next three months or so.”

On gold prices:

“I always buy gold and I own gold. I don’t even value it. I regard it as an insurance policy. I think responsible citizens should own gold, period.“

Fed Leaves Hedge Fund Bears Waiting in Bet on Emerging Markets

Ray Bakhramov has been waiting almost two years for his hedge fund’s bet against emerging markets to pay off, which spurred a 20 percent loss in 2012 and cost him clients. Even with a slump from bonds to currencies over the last five months, he’s still waiting.

Bakhramov, whose $180 million Forum Global Opportunities Fund posted gains this year after shorting South Korean and Turkish government debt and wagering against mining and steel companies reliant on developing economies, remains in the red on his bearish outlook. He says his best returns will come once central banks unwind their record stimulus, something the U.S. Federal Reserve unexpectedly refrained from doing yesterday.

“What we’ve seen so far is just a preview,” Bakhramov, 45, said in a telephone interview from New York this week. “A slowdown in any asset class is not a two-month or even a one-quarter phenomenon. When you go through a major repricing, the process of bottoming out typically takes about four years.”

Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke triggered the emerging-markets slump when he signaled May 22 that the Fed may curtail its bond buying, luring capital away from nations that offered higher yields and relatively low risk as long as central banks were backing the global economy. More than $47 billion has been pulled from global funds investing in emerging-market stocks and bonds since May, according to EPFR Global, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based data provider.

‘Bit Disappointing’

Hedge funds haven’t reaped the benefits of the emerging-market selloff because the currencies that fell the most this year aren’t easily bet against, some managers put on the wrong trades and volatility made it hard to stay in positions, investors said. What’s more, the worst of the emerging-market selloff may have already passed, analysts at Barclays Plc (BARC) and JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) predict.

“Performance has been a bit disappointing,” said Anthony Lawler, who oversees $6 billion invested in hedge funds at GAM in London. “Hedge-fund managers have been looking for something to break, and central banks have been trying very hard to not let anything break.”

Hedge funds focused on emerging markets, the investors who charge the highest fees to navigate developing economies, account for $155 billion of the industry’s $2.4 trillion of assets under management, according to Chicago-based Hedge Fund Research Inc. The funds slumped 0.8 percent on average through the first eight months of the year, with performance dragged down by money managers who lost money after failing to anticipate the slide for stocks, bonds and currencies, that Bernanke prompted four months ago.

Brevan Howard

The $2.7 billion emerging-markets fund at Brevan Howard Asset Management LLP, Europe’s second-largest hedge-fund firm, declined 12.7 percent this year through Sept. 13, and New York-based QFR Capital Management LP, a $3.5 billion firm that invests in developing nations based on macroeconomic trends, lost 13.4 percent in its fund through August, investors said.

Firebird Management LLC, a New York-based firm that oversees $1.1 billion in emerging-market equities and private-equity investments, restricted clients from pulling money from one of its funds in July due to “significant redemption requests coupled with the illiquid nature” of the holdings, according to a notice on the Bermuda Stock Exchange’s website.

A spokesman for London-based Brevan Howard declined to comment on the fund’s performance. Officials at QFR and Firebird didn’t return phone calls and emails seeking comment.

Hedge funds broadly gained 3.9 percent through August, HFRI data show, while the MSCI Emerging Markets Index lost 12 percent and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose 15 percent.

Fed’s Strategy

While booming economies such as in China, Brazil and India have been fueled by consumer demand, the bearish case against emerging markets is based on the view that global capital flows have primarily sparked asset gains. The combination of slower growth and the Fed curtailing its monthly bond purchases will accelerate the pace of redemptions, triggering a slump for stocks, debt and currencies, Bakhramov and other hedge-fund managers predict.

The Fed said yesterday that it wants to see more evidence that the U.S. economy is improving before reducing its bond buying. Economists had forecast the central bank would dial down U.S. Treasury purchases by $5 billion to $40 billion, while maintaining its buying of mortgage-backed securities at $40 billion, according to a Bloomberg News survey.

While emerging-market currencies are headed for their biggest annual decline against the U.S. dollar since 2008, those that fell the most after Bernanke first hinted at tapering, the Indian rupee and the Indonesian rupiah, haven’t led to windfalls for hedge funds, said GAM’s Lawler.

Currency Bets

The rupee and rupiah aren’t liquid enough to bet against in a meaningful way, leaving hedge funds to focus bearish wagers on currencies such as the South Korean won, which should fall if economic growth in China slows, Lawler said. The won trade hasn’t worked this year, as it’s gained 3 percent since May 22.

A trade that some hedge funds missed is the Brazilian real’s slide against the dollar, Lawler said. Instead of betting on the currency, money managers wagered that slowing growth would lead Brazil to cut interest rates, he said.

Stephen Jen, the former global head of currency research at Morgan Stanley (MS) who now runs London-based SLJ Macro Partners LLP, was one of the earliest and most vocal hedge-fund managers predicting an emerging-markets slump. He said during a February 2011 conference at the London School of Economics that emerging-market stocks and bonds would underperform. He’s since been quoted in articles by Bloomberg News, the Economist and other publications warning that slowing growth and the reversal of capital flows will crush currencies.

‘Significant Weakness’

Jen, whose firm also helps institutions and corporations hedge their risk to currency moves, remains convinced that the worst is yet to come. In a note to investors this month, he said the International Monetary Fund estimates that investors pumped $7.7 trillion into emerging markets over the past decade. Data indicate that just 10 percent of that has been pulled, and the Fed hasn’t even started tapering, Jen said.

“We remain firmly in the camp looking for further significant weakness,” he wrote in the Sept. 4 letter obtained by Bloomberg News. “Sell-side analysts have been too bullish on emerging markets based on the demographic trends, oblivious to the emerging-twin deficits, the overextended credit cycles and extreme valuation of both the currencies and the underlying assets.”

Fund Gains

Jen’s SLJ Macro Fund, which trades developed market and emerging-market currencies based on global macroeconomic trends, rose 13.3 percent in the first eight months of this year and is up 15.7 percent since it started trading in November 2011, the letter shows. Unlike most hedge funds, SLJ reports its performance excluding fees. The fund charges management fees ranging from 1.5 percent to 2 percent to oversee clients’ money and pockets either 15 percent or 20 percent of any investment gains it makes on trades, according to the investor note.

Jen, 47, declined to comment on his investment performance or how much money he manages at SLJ.

Russian-born Bakhramov, who previously structured asset-backed securities at Credit Suisse Group AG (CSGN), outperformed peers during Forum’s first six years of trading. He never posted an annual loss, a run that included an average annual gain of about 42 percent from the start of 2007 through the end of 2010, said investors, who asked not to be identified because the returns aren’t public. The hedge-fund industry had an average annual gain of 4.2 percent over the same four years, HFRI data show.

Difficult 2012

Then came 2012. Bakhramov positioned his portfolio for an emerging-markets slump and lost 20 percent. The hedge-fund industry rose 6.4 percent last year. Bakhramov told investors in his New York-based Forum Asset Management LLC that he watched in disbelief as central banks continued to pump endless amounts of money into the global economy.

With the Fed now laying the groundwork for pulling back, he said his time has come. The jump in interest rates prompted by Bernanke just talking about tapering shows that preventing a further rout in emerging markets may be beyond central banks’ control, especially if developing nations and companies start struggling to fund themselves, Bakhramov said.

Among the trades he’s put on is a bet against the Chinese yuan and buying credit-default swaps on ArcelorMittal (MT) and Glencore Xstrata Plc (GLEN), derivatives that pay out if the creditworthiness of the companies weakens, clients said. While the Forum fund was up about 6 percent this year through August, it lost money this month when emerging-markets rallied after China reported export and production figures that exceeded economists’ estimates.

Ali Akay

The September rally shows “people are still complacent that the Fed will take care of every problem,” Bakhramov said. “The mistake that people are making now is that they have accepted that emerging markets are an issue, but they don’t think it will be a big issue. We have our doubts.”

A hedge-fund manager who has successfully picked which emerging-market stocks will rise and fall this year is Ali Akay, a former SAC Capital Management LLC trader whose London-based Carrhae Capital LLP has gained about 9 percent through August, investors said. His $480 million hedge fund made money in July shorting potash companies that plunged after OAO Uralkali, the world’s largest producer of the soil nutrient, abandoned production limits that underpinned prices, a note to Carrhae’s investors shows.

Akay, 36, and Rob Kirkwood, Carrhae’s head of business development, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

No Clarity

In a short sale, traders bet stock prices will fall by borrowing shares from a broker and selling them. They plan to buy back the stock at a lower price, return the shares to their broker and pocket the difference as profit.

Investors should probably avoid hedge-fund managers wedded to either bullish or bearish views on emerging markets until there’s more clarity about the effects of the Fed curtailing its stimulus and the turmoil in the Middle East over Syria, said Alper Ince, who helps oversee $9 billion at Pacific Alternative Asset Management Co. in Irvine, California.

“You want someone who can trade these markets nimbly, going both long and short,” said Ince, whose firm invests in hedge funds on behalf of clients. “Emerging-markets underperformance looks overdone to me since May, but I’m not in the position to say now is the time to load up on exposure because there is so much uncertainty.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jesse Westbrook in London at jwestbrook1@bloomberg.net