The ECB’s very own tapering problem

September 24, 2013 Leave a comment

The ECB’s very own tapering problem

| Sep 24 14:59 | Comment | Share

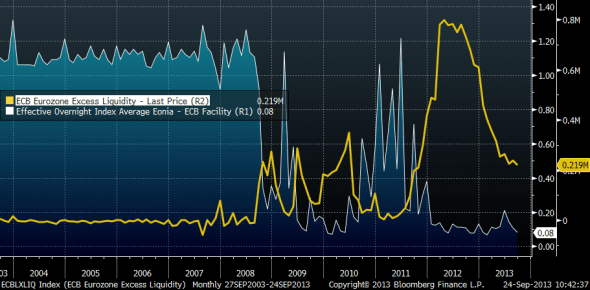

A while ago we speculated that because of the ongoing bifurcation of the eurozone market, Eonia rates could rise, and liquidity once again concentrate in core economies, as banks pay back their LTRO funds. Even if it appeared that the system could handle the repayments, banks in core economies would still be inclined to take advantage of extremely cheap negative rates available in collateral markets, so as to earn a spread on the deposit facility in a way that arguably encumbered the remaining liquidity. That would make it less available to periphery institutions. Meanwhile, without the additional layer of ECB liquidity in the system — which acts as a type of system-wide insurance mechanism — periphery banks would consequently be forced to make ever more competitive bids for Eonia funds, lifting rates across the board. In a note on Tuesday, Lena Komileva, chief economist at G+ Economics, stressed the degree to which excess liquidity had indeed been removed from the ECB system, and its greater than expected effect on Eonia rates (our emphasis): Excess liquidity in the Eurozone has fallen to €218.7bn, near its lowest level since end-2011. The decline is linked to banks’ repayment of the ECB’s 3yr LTROs, which in turn is linked to two developments: a reduction in market fragmentation and improved functioning of interbank markets, shrinking bank balance sheets due to recapitalisation pressures during the crisis which reduces lender demand for leverage but also curbs credit flows to the real economy .The ECB’s analysis has shown that there may be a significant link between a decline in excess liquidity below €200bn and unwanted tightening in market rates. The existence and direction of this link is indisputable: larger excess liquidity has pushed the Eonia rate closer to the ECB’s deposit facility rate. By the history of the last 7 years, the Eonia-deposit rate spread – currently at 7bps – will more than double to 20bps when excess liquidity in the Eurosystem drops below €200bn and it will rise further once it falls below €100bn. Based on the current pace of bank LTRO repayments, excess liquidity will fall to around €150bn by year-end.

LTRO repayment is thus pretty much ECB tapering. Except that unlike the Fed, the rate of the ‘unwind’ is being dictated not by central bank forces but by endogenous forces related to market demand. And banks, it seems, are keener to dispose of excess liquidity than many expected.

As we’ve noted before, this could be because one of the prevailing reasons healthy banks took the liquidity on in the first place was to exploit eurozone fragmentation carry trades. These can now arguably be funded more cheaply via repo markets, and/or take up too much room on balance sheets which are being forced to cut leverage ratios.

According to Komileva, it’s understandable on this basis why ECB President Mario Draghi should want to step up signals that another LTRO injection could be on the cards. The ECB in this sense has much less tolerance for higher market rates than most anticipated.

The Fed’s big “tapering miscommunication” meanwhile, has probably served as a useful window for the ECB into what can happen if rates rise before markets are ready for them.

As Komileva notes:

Hence it is no surprise that an imminent move below the psychological €200bn mark over the coming weeks has sparked off a debate as to the likelihood of further ECB action. Since a decline in interbank liquidity would effectively introduce an unwanted hike in overnight rates and extrapolate into a steeper euro money markets curve – a de facto tightening of euro monetary conditions – ECB President Draghi has signalled that the ECB stands ready to inject more long-term liquidity, in the form of another LTRO, in order to keep term money market rates low.

Over the summer we noted that the ECB will have to consider another long-term liquidity injection in order to: 1) lean against the Fed’s (now delayed) “tapering” lift in euro term rates, 2) arrest the domestic decline in market liquidity due to LTROs repayments, and 3) mitigate the unwanted growth effects from needed bank deleveraging in the form of tighter credit conditions for SMEs. It would appear that consensus is now moving in the same direction, which favours a flatter money markets curve.

The question is, would voluntary LTROs be sufficiently tempting for banks to take on at this stage? Banks, after all, are shedding liquidity because market fragmentation currently provides them with much better opportunities than carry trades. Also, there is increasingly a cost associated with holding too much liquidity.

If an LTRO was to be implemented, but the take-up was minimal, this could reveal the LTRO policy tool to be ineffective and force the ECB into exploring new policy tools, if not into more extreme and sizeable asset purchases.

Of course, if European rates were only responding to the Fed’s own taper talk rather than to LTRO repayments outright, there is a chance that rates could still settle down eliminating the need for additional liquidity.

Though, if the ongoing rate of LTRO repayments remains high, we fear this probably suggests otherwise.