Stock-Market Tail Wags Economic Dog

February 7, 2014 Leave a comment

Stock-Market Tail Wags Economic Dog

JUSTIN LAHART

Feb. 5, 2014 4:18 p.m. ET

The sudden, sharp drop in stocks is nothing to worry about. Yet.

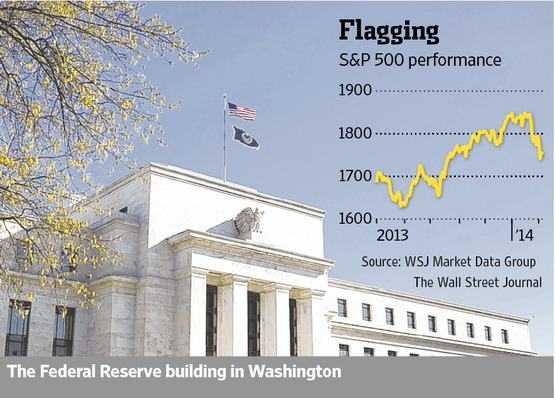

It has been a perilous time for markets. Trouble in emerging markets, a spate of softeconomic reports and the Federal Reserve’s decision to keep paring back bond purchases have set nerves on edge. In the past two weeks, the S&P 500 has fallen about 5%. Not since late 2012 has it fallen so far in so short a time.

Even so, the selloff has only taken the S&P to late-October levels. Given the scope of last year’s rally, and the pricey valuations it took stocks to, the drop may be no more than a welcome reality check for a market that got too exuberant. Even so, another leg lower might set the Fed on edge. Notwithstanding the late economist Paul Samuelson’s oft-repeated joke that the stock market “has called nine of the last five recessions,” when stocks swoon, it’s hard not to worry that the economy may follow suit.

Historically, the stock market has acted as an early warning system—albeit, an imperfect one—for the economy, often picking up on changes in the environment earlier than many other indicators. But while the line of causality mostly runs from the economy to stocks, there is also a feedback loop from stocks to the economy. If people’s retirement portfolios are suddenly worth less, for example, they are likely to be more cautious about spending.

The feedback loop may have become stronger in recent years. As ISI Group economist Ed Hyman points out, swoons in the stock market in 2010, 2011 and 2012 were each associated with runs of weak economic data that prompted the Fed to step up efforts to support the economy. Moreover, the Fed made clear that its efforts were aimed at easingfinancial conditions, turning the stock market into a yardstick of its success.

That might have led businesses to take more of their cues from the stock market. And even absent the Fed, after a recession that was precipitated by a collapse in financial markets, companies probably would have watched stocks more closely than before.

There also has been a more general change in corporate behavior that may have strengthened stocks’ influence. More companies are tapping measures like net present value to determine where to allocate resources, says John Graham, an economist at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business who has been surveying chief financial officers since the late 1990s. As with similar stock-valuation metrics, these use discount rates to account for the time value of money and risk involved in a project. The higher the discount rate, the bigger the payoff must be to make a project worthwhile.

When the stock market falls, its implied discount rate rises. In response, companies may then apply steeper discount rates internally, placing higher hurdles on plans to hire and expand. And the economy suffers as a result.

In that case, falling stock prices can become a self-fulfilling prophesy.