The tenacious mavericks who stick with their inventions

February 9, 2014 Leave a comment

February 6, 2014 5:55 pm

The tenacious mavericks who stick with their inventions

By Andrew Bounds

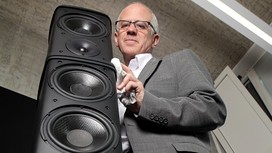

Dogged: Craig Milnes and his team have set themselves the goal of creating the perfect sound

What links a loudspeaker costing £65,000 and a supercar? The answer is a technology developed for audiophiles by a British company, which has been adopted in other sectors.

The kinship between a Wilson Beneschspeaker stack and a McLaren MP4 car illustrates how innovations in small niches can broaden into other applications. More importantly, it offers a reminder that the success of innovative technology often depends on persistence.

The speaker uses a new super-light, super-hard polymer in its case to improve sound quality. Wilson Benesch, its manufacturer in Sheffield, is one of those smaller, maverick companies that believes in a new technology and keeps plugging away. It has slowly emerged from a start-up in 1989 to a company that today has a name for developing breakthrough technology also used in other industries.

In doing so, it has had more research grants than any other small business from the Technology Strategy Board, which backs attempts to turn UK scientific strength into successful enterprises.

Founder Craig Milnes, a former steel engineer who also studied fine art, is a perfectionist. He says: “We have a clever team of people who do not want to do what has been done before. We want to provide better ways and more efficient ways of getting the perfect sound.”

Wilson Benesch was the first manufacturer to make a carbon fibre sub chassis turntable – an innovative high-end record player. Research begun when the company was first formed led to an innovative “resin transfer mould” technique in which resin is applied to carbon fibre and dried in a vacuum, which is easier, quicker and less expensive than traditional methods.

McLaren now uses the same RTM technique to cast carbon fibre parts for the cockpit of the MP4 car. Toyota has also adopted the same process.

In fact, carbon fibre itself might not have become widely used had it not been for persistent mavericks, says Sir Geoffrey Owen, senior fellow at the London School of Economics.

After an initial boom in the 1980s its use tailed off because of defence cuts. But in Japan, producers persisted with trying to refine it and find new applications. He says: “Getting these inventions to commercial market requires a degree of patience. Most investors want a quicker pay-off.”

Sir Geoffrey sees echoes in the experience of biotechnology companies. They had a boom after the human genome was mapped at the turn of the century, but the first gene therapies are only now coming through.

Sometimes, dogged innovators have to change tack, however. UK university spinoutEvocutis

created a revolutionary artificial skin that would replicate product testing on humans but found it hard to market. After more than 10 years of research and disappointing sales it now hopes to license its LabSkin intellectual property to a more established company.