Alibaba and the 40 cannibals; In the US, it took about five years for 10% of total customer funds (deposits plus MMFs) to be disintermediated by MMFs

March 14, 2014 Leave a comment

David Keohane | Mar 12 10:26 | Comment | Share

So. Alibaba’s Yu’e Bao and its internet Money Market Fund ilk are good, particularly if you are in favour of deposit liberalisation in China, say, in 1-2 years. As Lex said, Yu’e Bao is sneaking market-priced bank capital into a closed system.

But. Yu’e Bao and its ilk are bad, particularly if you focus on pesky things like liquidity risk. This is nuts. When’s the危机? after all, and it’s worth remembering the risk that comes with receiving higher returns than capped bank deposits.

Meanwhile. Yu’e Bao and its ilk are a threat, particularly if you are a Chinese bank…

Say you are, in fact, that Chinese bank and your deposit base is being sapped by all of these upstarts. Heck, Yu’e Bao alone has more investors than the country’s equity markets and according to the FT had accumulated at least Rmb500bn ($81bn) in deposits by the second week of March, making it the fourth largest money-market fund in the world.

What do you do in response to that kind of growth? Two things, apparently: you cap transfers and you start your own internet MMF. From Citi (with our emphasis):

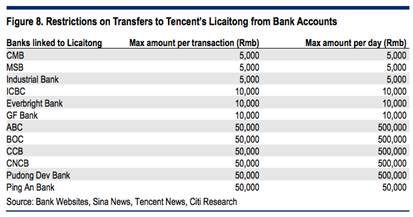

The explosive growth in Yu E Bao has triggered banks to respond. Some banks have set limits on funds transfers to internet MMFs like Yu E Bao, for example CMB and MSB limit transfers to Rmb5,000 per day to Tencent’s Licaitong, to stem the outflow of deposits (Figure 8); we believe this may buy a little bit of time but is overall an ineffective response.

In recent weeks, numerous banks including the big banks (ICBC, BOC) and joint stock banks (CMB, MSB, Ping An Bank) have started to launch their own internet T+0 redemption MMFs (Figure 9). Bank MMF returns are somewhat lower than those offered by the internet companies but they are still significantly higher than bank deposit rates. We believe this is a critical development – to defend their customer base, banks have no choice but to launch their own MMF products and cannibalize their own deposit base. At least they are cannibalizing their own customers with their own products rather than someone else’s and hence banks can still hope to retain the customer relationship. This trend of deposit disintermediation by MMFs clearly has destructive implications for the sector.

We suppose that it’s part of the supposed master plan, after all the central government is still the largest shareholder in the four big state banks (some 60-70 per ownership) and has been supportive of the internet competition. Even more so, if they started to poses a real threat to the system the PBoC would probably just shut them down. But, even if this is broadly a good thing in terms of forcing some market reality into the system, there are some not inconsequential issues to be worked through.

First, for the MMFs and the funds they take in — although they appear to be demand deposits they aren’t regulated as such. That leads to obvious worries about redemptions, liquidity risk and runs especially if regulation changes, banks stop buying MMF deposits as there’s only so many interbank deposits they can use (they don’t count toward meeting the 75 per cent loan deposit ratio ceiling) and returns drop.

Second, for the banks who are being forced to compete and who face a tough combination of deposit outflows (lower volumes) and higher funding costs (lower NIMs) in the next few years. From Citi:

There are sufficient similarities between China today and the US in the 1970s (e.g., deposit rate regulations, interest rate environment) to suggest further deposit disintermediation is in the cards for China. The implication for the banking sector is massive because demand deposits – the type of deposit that is most susceptible to being disintermediated by MMFs in our view – currently make up roughly half of all deposits in the banking system and are the bedrock of the banking system’s profitability. If demand deposits flow out of the banking system into MMFs, the profitability of banks will be seriously affected. We lay out some sensitivities below, but the eventual impact is highly uncertain because of the many moving parts that need to be considered over the medium term.

…

In the US, it took about five years for 10% of total customer funds (deposits plus MMFs) to be disintermediated by MMFs, 10 years for 15% disintermediation and 15 years for 20% disintermediation. The peak was in 2001 when 37% of customer funds were in MMFs.

There is good reason to believe that developments in China could happen faster today given better technology and information. Let’s say it will only take China five years to get to where the US was after 15 years, i.e., 20% of deposits will be disintermediated by MMFs in China, then the CAGR in total banking system deposits would fall to just 7%, demand deposits would hardly grow, the proportion of demand deposits would fall to 38% of total deposits (down from 50% currently) and NIM would narrow by 33bps due to the shift in deposit mix (assuming no change in deposit costs from current levels).

…

Without any positive offsets [such as a cut in RRR and the increase in loan prices] the combined effects of deposit disintermediation and deposit rate liberalization could mean minimal net interest income growth or even moderate net interest income contraction for the sector over the next five years. Figure 18 below combines the volume and NIM impact into net interest income impact. In a modest scenario whereby 10% of deposits are disintermediated in five years (same time schedule as the US in the late 1970s) and time deposit costs rise 100bps, the system will still see just 3% net interest income CAGR. But in a severe scenario where 20% of deposits are disintermediated, net interest income CAGR becomes negative 5%. This exercise highlights the revenue uncertainty and challenge that deposit disintermediation and rate liberalization brings to the sector.

And third, for the economy at large, from Citi once more:

Constraint on bank lending – Many banks, especially the mid/smaller sized banks, have LDRs that are close to the 75% regulatory limit. These banks can only grow loans in-line with deposits and if deposit growth becomes constrained due to disintermediation by MMFs, then loan growth will also be constrained. This 75% LDR ceiling has just been included in the CBRC’s revised liquidity framework for commercial banks and so it seems that this requirement is here to stay, although we do not rule out some tweaking of loan or deposit definitions to ease the pressure on banks.

Shadow banking/ capital markets expansion – Expansion in MMFs will be a catalyst for capital markets development as MMFs are important investors in high-quality short-dated securities. This will accelerate the expansion of direct financing activities outside the banking system (e.g., commercial papers, asset backed securities). In the US, MMFs have been a key factor behind the growth of the shadow banking system, which ultimately led to the global financial crisis. MMFs in the US invested heavily in short-term asset-backed commercial papers (ABCP), which were issued by finance companies, SIVs (structured investment vehicles) and conduits. These entities were then using this funding to invest in subprime CDOs.

PBOC credit policy – The disintermediation of deposits and lending by the capital markets will be a challenge to the PBOC’s credit controls and targets. This also means that the PBOC needs to rely on and develop more policy tools and shift away from quantitative tools like loan quotas and toward interest rate tools.

Encourage banks to take more risks – The funding cost pressure arising from the loss of cheap demand deposits and deposit rate liberalization will encourage banks to earn higher returns by taking greater balance sheet risks. This is already happening with many mid/smaller sized banks repositioning their focus on higher yielding micro enterprise lending. Investors should bear in mind that the US savings and loan crisis in the 1980s was partly the result of deposit rate liberalization, which pushed up funding costs for S&L banks, and lending deregulation, which allowed S&L banks to excessively pursue higher risk commercial and property lending.

Higher cost of capital – Under funding cost pressure, banks will try to price up their loans to all types of borrowers; borrowing costs across the economy will therefore rise.

Pace of deposit rate liberalization is effectively happening already through the back door beginning with WMPs a few years ago that disintermediated time deposits and now MMFs are threatening to disintermediate demand deposits. Should the PBOC accelerate deposit rate liberalization to allow banks to compete with MMFs and retain their deposits, or will the PBOC continue on a more gradual time schedule and banks will suffer significant disintermediation of their low cost deposits? At a press conference held on March 11th, PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan said deposit interest rates will most likely be liberalized in one or two years. This timetable is more aggressive than our expectation