Fitch: China’s credit is not just big, it’s growing way too fast

September 22, 2013 Leave a comment

Fitch: China’s credit is not just big, it’s growing way too fast

Sep 18, 2013 11:08am by Rob Minto

Some more fuel to the China-credit-is-out-of-control fire. Fitch Ratings (which, don’t forget, downgraded China’s debt rating last year) has published a report which argues that “talk of deleveraging, or contracting credit, is misplaced” and warns that “no financial system can sustain rising leverage indefinitely”. And Fitch has a few scary numbers and charts to show the extent of the problem. The report starts by looking at how debt is still climbing: Leverage continues to rise rapidly in China’s economy. The rolling 12- month sum of net new credit hit CNY 21trn in August 2013, based on Fitch Ratings’ measure of broad credit (2012: CNY19trn), marking the fifth year that net new credit will exceed a third of GDP. Certain forms of credit are shrinking, but overall extension remains high, a substantial portion of which is appearing in channels excluded from official data. Talk of deleveraging, or contracting credit, is misplaced, with the stock on pace to rise 20% in 2013. This chart illustrates that growth:

As Fitch puts it, China’s reliance on credit isn’t going away:

As Fitch puts it, China’s reliance on credit isn’t going away:

True deleveraging, in which credit growth is below nominal GDP growth, is not on the cards – given the continued heavy reliance of economic growth on credit.

As the FT’s Simon Rabinovitch pointed out in a series on China’s debt dragon:

Total debt in China – government, corporate and household – has shot up from 130 per cent of gross domestic product in 2008 to nearly 200 per cent today, or more than Rmb100tn ($16.3tn), according to Chinese central bank data.

And Fitch thinks that could rise to 270 per cent by 2017.

So what? Other countries have similarly high ratios, including the US and Japan. What’s the worry?

Well, for Fitch, it’s the pace of expansion, not just the size that matters.

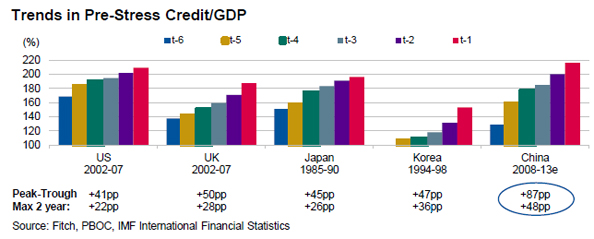

Fitch notes that credit to GDP will have risen by around 87 percentage points in the five years ending in 2013, nearly twice the pace in other countries prior to the financial crisis.

It is difficult to see how a situation in which credit – already twice as large as GDP – continues to grow by twice as fast can be sustainable indefinitely. Nonetheless, there appears to be no immediate constraints to prevent this divergence from continuing.

So where are the risks? Households have increased their debt burdens, but from such a low base that it’s not the major worry. The bigger concern is for corporate debt and local governments. Chinese corporates have taken on the biggest debt burden of any sector, and “the profit growth of Chinese companies has fallen far short of their rise in indebtedness”.

Equally, local governments are vulnerable. The total here is hard to work out as local governments use shadow financing such as entrusted loans, wealth management products and other non-bank credit, as well as loans reported to the regulator. Fitch estimates an overall figure of 32 per cent of GDP, or Rmb18.5tn in the first half of 2013. The challenge here is liquidity, as typically the interest on the loans is repaid but not the principle, which is rolled over, making such loans more like perpetual bonds.

Fitch calculates that total interest due on debt has risen from an estimated 7 per cent of GDP in 2008 to 12.5 per cent in 2013. And it’s getting worse:

By the end of 2017, this will rise to an estimated 16 per cent under a positive scenario that optimistically assumes no upward movement in interest rates and steady annual nominal GDP growth of 11 per cent. More realistic scenarios are much bleaker.

Fitch suggests that the high levels of new credit point to interest on existing loans being refinanced – in other words, doubling down on the debt. Fitch calculates that up to 17 per cent of the increase in new credit could consist of interest on previous debts alone. Which means that the collateral backing loans is shrinking as a proportion of credit. That’s not good news if there is a fall in asset prices.

Overall, it puts Chinese policy makers in a bind:

This underscores the practical limits on China’s financial liberalisation in a climate in which debt burdens have become so large. Whether these issues will actually prompt policymakers to slow deposit rate liberalisation – which is widely believed would lead to significant upward pressure on funding costs, and, by extension, borrowing costs due to tight financial sector liquidity – remains to be seen. Any aggressive push forward has the potential to introduce volatility, in light of the country’s massive and rapidly expanding debt load.

Curbing credit growth will be tricky, to say the least.