Student-Loan Defaults Rise in U.S. as Borrowers Struggle

October 1, 2013 Leave a comment

Student-Loan Defaults Rise in U.S. as Borrowers Struggle

About one in seven borrowers defaulted on their federal student loans, showing how former students are buckling under higher-education costs in a weak economy. The default rate, for the first three years that students are required to make payments, was 14.7 percent, up from 13.4 percent the year before, the U.S. Education Department said today. Based on a related measure, defaults are at the highest level since 1995.The fresh data follows the announcement by Barack Obama’s administration that it would seek to restrain skyrocketing college expenses by tying federal financial aid to a new government rating of costs and educational outcomes. The rising number of defaults shows the pain of borrowers, said Rory O’Sullivan, policy and research director at Young Invincibles, a Washington nonprofit group.

“Our generation is behind in the economic recovery and not recovering as fast as we need to,” said O’Sullivan, whose group represents the interests of people ages 18 to 34. “It’s financial disaster for borrowers. Defaults can dramatically affect their credit rating and make it harder to borrow in the future.”

270 Days

Today’s report covers the three years through Sept. 30, 2012. The default rate, which includes graduates and those who dropped out, shows the share of borrowers who haven’t made required payments for at least 270 consecutive days.

The rate doesn’t include those who are putting off payments, through deferral or economic hardship called forbearance, or borrowers who are on federal income-based repayment programs, meaning it understates their hardship, O’Sullivan said.

U.S. borrowers owe $1.2 trillion in student-loan debt — including government loans and those from private lenders such as SLM Corp. (SLM), commonly called Sallie Mae. That sum surpasses all other kinds of consumer borrowing except for mortgages.

Last year, the Education Department revamped the way it reports student-loan defaults after Congress demanded a more comprehensive measure because of concern that colleges counsel students to defer payments to make default rates seem low. Previously, the agency reported the rate only for the first two years that payments are required.

Worst Performers

Public colleges reported a 13 percent default rate while nonprofit private schools had a rate of 8.2 percent. For-profit colleges fared the worst, at almost 22 percent.

Under the older two-year measure, the rate for all colleges was 10 percent, up from 9.1 percent the year before — and the highest since 1995.

“The growing number of students who have defaulted on their federal student loans is troubling,” U.S. Education SecretaryArne Duncan said in a statement. “The Department will continue to work with institutions and borrowers to ensure that student debt is affordable.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Janet Lorin in New York jlorin@bloomberg.net; John Hechinger in Boston at jhechinger@bloomberg.net

September 30, 2013, 8:15 p.m. ET

Student-Loan Straitjacket

Filing for Bankruptcy Usually Ends Up Increasing School-Debt Balances

KATY STECH

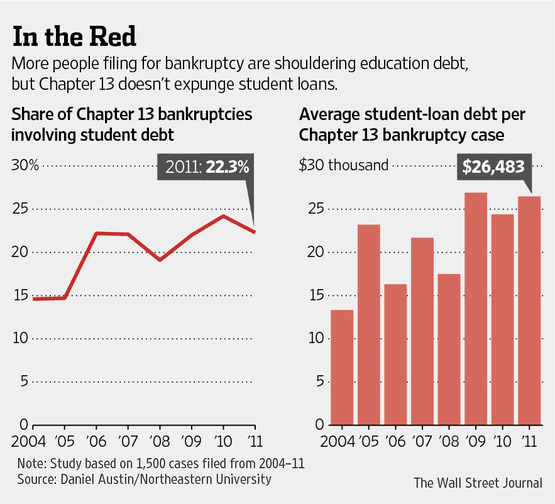

People struggling to pay down student loans and other debt may resort to filing for bankruptcy, which generally offers a fresh start. But they often end up owing even more on their student borrowing at the end of the process.

Under the federal bankruptcy code, consumers almost never can get rid of student loans—unlike credit-card, medical and many other types of debt. The rule is meant to prevent people from filing for bankruptcy soon after they leave college in an attempt to renege on their school loans.

On top of that, the process under Chapter 13 of the code generally restricts these borrowers from making full payments on student loans during the three-to-five-year bankruptcy period. That allows lenders to add interest, late fees and other penalties to the student-loan balances during that time.

The upshot: Aside from rare cases, student loans are the only consumer debt that ends up larger after bankruptcy.

The rules have come under fire from some federal lawmakers, bankruptcy attorneys and consumer advocates.

“This provision takes a bad situation and makes it worse—forcing people in financial trouble to divide their meager resources so that they can’t stay current on their student loans,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.), a consumer-protection advocate. “This is fundamentally the wrong approach.”

It isn’t clear how many of the roughly 1.2 million Chapter 13 bankruptcy cases filed overall by individuals in 2010, 2011 and 2012 included student loans. But lawyers across the country say their bankruptcy clients have ever-larger education debts.

Some bankruptcy experts say the problem shows the U.S. Bankruptcy Code is ill-equipped to handle student-loan debt, which, at about $1 trillion, has outgrown credit cards as the largest source of consumer debt, excluding mortgages.

Pennsylvania resident Daisy Ellerbee, 38 years old, has two years of payments left on her Chapter 13 bankruptcy plan and now owes more than $30,000 on a loan that she co-signed for one year of her daughter’s education at West Virginia University. The original loan amount was $24,700, she said.

“They kill you with the interest rate,” said Ms. Ellerbee, who said she and her husband filed for Chapter 13 after a series of setbacks, including the 2006 flooding of their home.

Pennsylvania bankruptcy attorney Patricia Mayer said that situation isn’t uncommon. “At the end of the day, I’m going to have clients coming out after five years owing more than when they went in [on student loans], and that’s not fair, and that’s certainly not a fresh start,” she said.

Deeply indebted consumers use Chapter 13 when they make too much money to qualify for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, which is reserved for people with little or no disposable income.

Unlike Chapter 7, which starts a court-supervised sale of a debtor’s assets, Chapter 13 allows a borrower to try to save major assets such as a house.

Ending up with a higher student-loan balance “was a lesser of evils at the time,” said Shawn McKendry, who filed for Chapter 13 in 2009 to reduce the amount of debt on his house, located near Malibu, Calif., which was worth $120,000 less than what he owed on his mortgage then.

The 32-year-old telecom finance executive said the $58,000 balance on his student loans has grown by several thousand dollars since he filed. “I’m waiting for that ticking time bomb to get me when I’m out of Chapter 13,” Mr. McKendry said.

Some creditors in personal- bankruptcy cases, such as credit-card issuers, could oppose any move to allow borrowers to make full payments on student loans during bankruptcy, since that could cut into their payments.

The American Financial Services Association, a trade group that represents credit-card issuers, wouldn’t specifically comment on whether bankruptcy-repayment rules should be changed. Executive Vice President Bill Himpler said broadly that “there needs to be certainty and fairness among how creditors are treated” in bankruptcy.

Sen. Richard Durbin (D., Ill.), who has spearheaded student-loan debt-forgiveness legislation, said bankruptcy-repayment plans that cause student-loan balances to rise are “driving borrowers further into debt and denying people the fresh start that bankruptcy promises.”

Mr. Durbin, whose staff wasn’t aware of the issue until contacted by The Wall Street Journal, later sent a letter to the Justice Department’s bankruptcy-court-monitoring division, the U.S. Trustee Program. In it, he urged the division to allow borrowers to keep making full payments on student loans through a loophole already used by a handful of judges and trustees.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. Trustee Program declined to comment on his suggestion.

Democratic lawmakers, including Mr. Durbin, earlier this year floated legislation to allow private student-loan debt to be discharged in bankruptcy. However, the proposal doesn’t address federal loans, the bulk of outstanding student debt, and doesn’t clarify Chapter 13’s repayment rules.

Falling behind on student loans can have other consequences. In 2009, a Florida optometrist told Bankruptcy Judge John K. Olson that she could lose her professional license if state regulators found out she defaulted on her student loans.

Judge Olson allowed the woman to keep making full payments, but lawyers say fighting for such exceptions can be an expensive battle with a high risk of failure.

More recently, Judge Olson blocked a student lender from charging a bankruptcy filer late fees, collection fees “or any other penalties based solely upon its [payments] being less than the minimum monthly payments it would otherwise be contractually entitled to,” according to the court order.

“Allowing [the lender] to assess penalties would impair the fresh start and undermine Congress’ goal” in Chapter 13, Judge Olson wrote.