Millions of poor people during Brazil’s decadelong boom took out loans to speed their rise to the middle class. Now comes the less glamorous side of a consumer’s life: paying off debt

October 9, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated October 8, 2013, 11:18 p.m. ET

Bill Comes Due for Brazil’s Middle Class

Debt Woes Help Explain Why the Country’s Once-Dazzling Growth Has Fizzled

SÃO PAULO, Brazil—Like millions of poor people during Brazil’s decadelong boom, Odete Meira da Silva took out loans to speed her rise to the middle class. The single mom bought a computer, a flat-screen TV and started building a concrete home on the rough southern edge of this sprawling city. Now, her spending spree is over. The 56-year-old small-business owner is today concerned with a less glamorous side of middle-class life: paying off debt. After her ballooning credit-card bills exceeded what she could afford, she cut back on everything and stopped home construction. On a recent day, a bare concrete staircase rose from her living room to an unfinished second floor. It is a reminder of her own halfway climb up Brazil’s economic ladder.“I still plan to finish the house, but it will have to be done bit by bit, maybe in three more years,” she said, sitting in her living room, the only part of the house completed before she ran out of money.

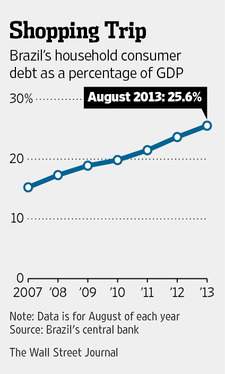

Ms. Silva’s debt woes help explain why Brazil’s once-dazzling growth has fizzled and isn’t expected to blast off again soon. Most people think of Brazil—among the world’s biggest producers of iron ore and soybeans—as a poor country that lives or dies on sales of commodities. But aspiring shoppers like Ms. Silva fueled much of the country’s recent boom, as consumer loans more than doubled to around $600 billion in five years.

Now, many of these new shoppers are suffering from credit-card fatigue—or worse. Some are defaulting on Brazilian credit cards that can charge 80% annual interest or more. Facing more defaults, banks are now warier about lending.

As a result, consumption is expanding at its lowest rate since 2004. That is compounding other problems, including weaker exports to China and a manufacturing slump caused by a strong currency, that were already slowing Brazil down. With consumer confidence declining, Brazil’s gross domestic product is expected to post 2.4% growth this year, after reaching 7.5% in 2010.

Complicating matters, Brazil’s consumption boom sparked 6% inflation as demand for goods outpaced the economy’s ability to supply them. That has put Brazil’s central bank in the uncomfortable position of raising interest rates to control inflation amid a sluggish economy, a move that could slow growth even more. Economists expect the central bank to raise its already high 9% benchmark rate by a half percentage point during a policy meeting Wednesday.

Brazil’s troubles offer a warning to emerging markets caught up in one of the most enticing economic stories of the past decade: the rise of middle-class consumers in the developing world.

From Brazil to Indonesia to South Africa, faster growth rates lifted millions from poverty in the last 10 years, bringing more people into the middle class and introducing many of them to credit for the first time. But while economists mostly view such credit expansion as a good thing, the case of Brazil shows how middle-class growth can also be knocked off track by too much debt.

In Thailand, household debt soared 88% between 2007 and 2012, in part due to government stimulus programs that encouraged car sales. In South Africa, consumer loans have reached nearly 40% of gross domestic product, more than twice the average of its developing world peers. Russian consumers put nearly 80% more on their credit cards last year than the year before.

While workers in China are known as savers, not borrowers, the country is now trying to push its population to consume more to extend its recent boom.

But Brazil’s consumer credit troubles stand out among big developing economies. Consumer lending rose at an annual average rate of 25% in the four years after the global financial crisis of 2008. As of June 2013, some 5% of Brazilian consumer loans were 90 days overdue, twice the rate of India and more than Mexico, South Africa and Russia, according to Fitch Ratings.

“All these people have been spending more than they have, creating an illusion of economic growth,” said Vera Remedi, an executive at Procon São Paulo, a Brazilian government agency that advises people like Ms. Silva on how to manage or renegotiate their debts.

Part of the problem, some economists say, is that Brazil focused too heavily on policies designed to increase consumption instead of completing ports and roads to help economic production in the long term. Brazilians bought a lot of flat screens during the boom, but the country’s ports are still so clogged some ships turn away instead of waiting.

“Brazil’s external borrowing was spent on trips to Disneyland, suitcases packed with goods straight from New York or Miami,” said Paulo Leme, who runs Goldman Sachs’ business in Brazil. “That will have consequences in the future.”

Finance Minister Guido Mantega and others say Brazil’s economy is getting caught in a global slowdown and that matters would be even worse without measures to increase consumption.

Brazil’s credit problems aren’t expected to return the country to the kinds of crises that destroyed middle classes of generations past, economists say. Brazil’s total outstanding bank loans, including commercial and consumer debt, are around 55% of GDP, which is low by international standards.

The country’s banks are sitting on large capital reserves, which should help Brazil weather any deeper downturn. The central bank’s reserves of $372 billion are a tenfold jump from a decade ago.

All the same, consumer-debt worries have prompted a rethink on how far Brazil’s new middle class will climb, and how fast. The percentage of household income that goes to pay off debts is unusually high: In Brazil, it is more than a fifth of household income compared with 10% in the U.S., according to both countries’ central banks. That is largely because Brazil’s lending rates are sky-high, a leftover from years of economic crashes. The interest on an average loan is 37%.

Plus, the profile of Brazilian debt isn’t as healthy as it is in countries like the U.S. A big chunk of U.S. borrowing is home loans, seen as healthier since home prices can rise. But Brazil’s mortgage market is tiny. Brazil’s consumer debt went largely to appliances and cars—items that lose value.

Car sales are an example of how the credit boom played out. Auto loans more than tripled between 2004 and 2010 to around $70 billion a year, as consumers clamored to own a key symbol of middle-class life. Banks were lending with no money down, a previously unthinkable concept in the country.

Last year, there were 2.9 million new cars registered in Brazil, a 130% increase from a decade ago. Economists started pointing to massive traffic jams of entry-level hatchbacks as symbols of development.

“At one point, I was selling cars with 80-month financing to people who made $500 a month,” said Adalberto Fava, sales manager of a Hyundai dealership that serves a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of São Paulo. “I knew there was no way they could afford it,” with monthly payments as high as $200. Many of these cars were repossessed, he said.

One such buyer was Jorge Luiz Bispo, a married 44-year-old father of one. With an elementary education and few prospects, Mr. Bispo saw a chance to leave his poor childhood in the northern state of Bahia behind. He borrowed money from a bank to buy his family’s first car, a used Volkswagen.

For a while, credit financed Mr. Bispo’s climb into the entrepreneurial class. He also borrowed $4,200 to start a small business, a beauty salon. He borrowed more to send his wife to a four-year beauty program.

Within six months, the family was behind on loan payments, largely because it had underestimated how much debt it could afford. Ms. Bispo had to drop her college classes. The bank took their car. The couple is trying to hang on to the salon, but it is bleeding money as neighborhood customers, some grappling with their own debt problems, shy away, Mr. Bispo said. The Bispos are defaulting on some bills.

“Each month, we have to decide which bills we can pay. We’re having a financial crisis,” he said.

Political leaders worked hard to expand consumption, hoping to close the historically wide gap between rich and poor in Brazil. Under Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, a poor union leader elected president in 2002, and his successor, President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil hired tens of thousands of new government workers and expanded its welfare system. It subsidized gasoline and electricity prices and directed government banks to unleash billions in consumer loans.

The strategy helped lift living standards and spurred growth. In 2009, Mr. da Silva cited the growing middle class in a successful pitch to hold the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, an event he said would help correct inequality and inspire a poor continent. But policy makers failed to match their consumer-friendly steps with measures to improve productivity and long-term growth, many economists say.

Plans to improve ports, roads and sanitation stalled. In 2007, Brazil announced a $250 billion infrastructure investment program to make the economy more efficient. But many of the most important projects—new roads in the poor Northeast, new trains, irrigation canals and better ports—have been delayed by years amid poor planning and execution, analysts say.

The result: Consumption kept growing even as the rest of the economy was showing strains from weakening commodity prices and an overvalued currency. Brazilian tourists, many of them flying overseas for the first time, were among the biggest spenders among foreign tourists to New York City last year, city officials said.

Back at home, industrial production shrank as Brazilian factories lost ground to global rivals. This mismatch between consumer demand and economic output fueled rising inflation, economists say.

“The government insists on trying to get people to consume, but on the other hand, the supply, the industries, the companies, haven’t produced that much,” said Samy Dana, a professor at Fundação Getulio Vargas university in São Paulo.

Ms. Rousseff, who faces elections next year and gets many of her votes from the country’s poor, has signaled plans to keep pushing more consumption. She recently announced a minimum-wage increase and a plan to provide an additional $8 billion in credit to low-income families.

Brazil’s development bank, BNDES, said disbursements will rise 22% this year, after a 12.3% rise in 2012.

Ms. Rousseff announced Sept. 2 that Brazil’s government lent around $500 million in three months so people in a subsidized home mortgage program could buy home appliances, too. Through the program, called “My Better House,” the government extended credit lines to participants to spend on a list of approved items such as refrigerators, televisions and beds.

All the same, people like Ms. Silva in the unfinished house in São Paulo have to find ways to cut back. Her family keeps the lights off and takes short showers to save on utilities. She worries cold drafts from the dusty unfinished second floor are aggravating her youngest son’s asthma, she said.

Though Ms. Silva’s income of about $26,000 per year makes her a solid member of the middle class, her gains are precarious.

The family doesn’t have a lot of education. Her eldest son went to work in his teens. Her youngest wants to go to college, but Ms. Silva is concerned he won’t get in. The teachers at his public school are often on strike, creating gaps in his learning.

Crime is her biggest concern. They live in a rough neighborhood in a country with one of the highest murder rates in the world. Almost everyone in her family has had cars they financed stolen. Her eldest son recently lost a used $15,000 Volkswagen. He still has to make payments on the car, even though it was stolen.

Ms. Silva is an energetic woman who took advantage of government subsidies and credit to climb up the ladder. Barely getting by as a store clerk a decade ago, she heard that the government was hiring drivers to offer free school busing.

She decided to buy a bus and go into business. She sold her small apartment to raise half the $28,000 she needed. She borrowed the rest through bank loans and credit cards.

She racked up debts on three credit cards, buying household goods and $5,000 worth of building materials. At high interest rates, the debt on the construction materials alone more than doubled to about $11,000.

Now Ms. Silva is digging out from her debt. She cut deals with her lenders who agreed to lower her interest payments, reducing what she owed by several thousand dollars.

But other challenges loom. She must buy a new school van next year to keep her contract as part of a government rule designed to increase vehicle consumption. In Brazil’s tightening lending market, getting a loan this time will be harder.

She says she isn’t worried: “I believe things are getting better.”