From salaried workers to business legends to failed tycoons: Were they too arrogant or is Korea no place for self-made entrepreneurs?

October 14, 2013 1 Comment

2013-10-13 14:01

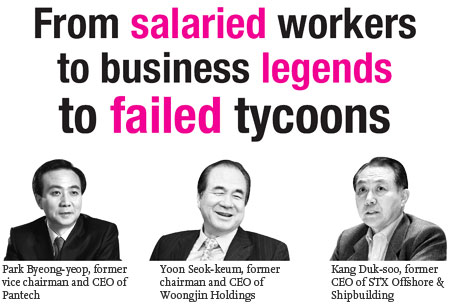

From salaried workers to business legends to failed tycoons

Were they too arrogant or is Korea no place for self-made entrepreneurs?

By Kim Da-ye

The chief executive officers who recently stepped down from the large conglomerates or corporations they had built on their own share a common background — they started their careers as salaried employees. These failed tycoons include Yoon Seok-keum of Woongjin Group, Kang Duk-soo of the shipbuilding-focused STX Group and Park Byeong-yeop of handset maker Pantech. Yoon was formerly an ace salesman at Encyclopedia Britannica. Kang’s first job was at SsangYong Cement, whose key affiliate he later acquired. Park spent his mid-late 20s at Maxon Electronics as a salesman.These men were once dubbed “living legends of salaried workers” and admired for being self-made “owners,” while Korea Inc. is dominated by long-established conglomerates run by second- and third-generation offspring of the founders. While many mid- and large-sized corporations are struggling amid the prolonged sluggish economy, the downfall of Yoon, Kang and Park drew particular attention from the public and the media for that reason. Some lament that Korea is no longer a country for rags-to-riches entrepreneurs.

The Korea Times’ Business Focus asked economists and analysts what brought about the demise of those CEOs, what it means for other surviving “salaried workers’ living legends,” and how entrepreneurs may avoid falling into the same trap. There is a clear theme across various opinions — “Don’t try to copy chaebol.”

The fallen

Yoon’s Woongjin Group started as a publishing company that he set up in 1980 after leaving Britannica. The firm was later renamed Woongjin Think Big and became a major study materials publisher in Korea. In the 1990s, he expanded to the then unusual business of renting water purifiers and to the food industry with a focus on healthy drinks.

The group’s aggressive expansion came in the mid 2000s. In 2007, it acquired Kukdong Engineering and Construction from U.S. private equity firm Lone Star. Kukdong E&C went bankrupt during the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s. The entrepreneur also made a foray into the chemical industry by buying Saehan in 2008. A year later the firm entered the solar power industry by founding Woongjin Polysilicon and Woongjin Energy.

In September last year, however, Woongjin Group’s finances crashed because of the losses caused by Kukdong and the solar-energy business. Both real estate and solar energy markets slowed down badly during and after the global financial crisis. Woongjin was declared bankrupt, and Woongjin Holdings and Kukdong entered a court-managed workout program. Yoon stepped down from the CEO position of the holding company. Woongjin recently succeeded in selling Woongjin Foods and Woongjin Chemical and paying back some of its debt. On a positive note, analysts expect the firm to graduate from the court receivership program earlier than expected within this year.

STX Group also grew through mergers and acquisitions (M&As). When SsangYong Group collapsed in 2000 after the Asian Financial Crisis, Kang, the then executive in charge of finance at SsangYong Heavy Industries, couldn’t let the company disappear, so he acquired it with his own money. In 2001, he renamed the company as STX, and a few months later he acquired a shipbuilding firm that became STX Offshore & Shipbuilding. In 2002 the company purchased a power-generating firm, which is now STX Energy, and in 2004 a shipping company, now STX Pan Ocean.

In 2007, STX expanded globally by acquiring Norwegian cruise-ship maker Aker Yards, and in 2008 they completed a massive shipyard in Dalian, China. By 2009, STX Group was the 12th largest conglomerate by assets in Korea. In 2011, when Hynix Semiconductor came out to the M&A market, Kang made a bid for it, competing against SK Group. Hynix ended up in SK’s hands as STX gave up, citing the lack of funding amid uncertainties in the global economy.

As the recession of the shipping and shipbuilding industries became prolonged, STX’s liquidity dried up quickly. In June, the company filed for bankruptcy with the shipping affiliate entering court receivership. The creditors have taken charge of the restructuring program for the shipbuilding arm. Kang gave up his chairmanship at the shipbuilding affiliate due to the creditors’ demands.

Pantech is the third firm whose self-made CEO stepped down because of soured business. Park’s case is different from those of Yoon and Kang because Pantech stayed in one industry.

Park founded in 1991 Pantech, Korea’s third-largest handset maker, which produced beepers in its early years. In the late 1990s, the firm produced mobile phones, largely as an original equipment manufacturer. It had a strategic partnership with Motorola for supplying handsets.

In 2001, Pantech acquired Hyundai Curitel, an affiliate of Hyundai Electronics, and entered the domestic handset market with its own brand. In 2005, the firm acquired SK Teletech, a supplier of the SKY-brand mobile phones to SK Telecom, and expanded to the U.S. and Japan.

In 2006, Pantech declared bankruptcy and applied for a workout by the creditors. While Pantech was restructured under the creditors’ guidance between 2007 and 2011, Kang endeavored to revive the company by developing smartphones earlier than some of its competitors. In 2010, the firm sold more smartphones than LG Electronics in Korea.

Due to the intensifying competition, however, Pantech plunged into losses in the third quarter of 2012 and has not recovered yet. In September, Park decided to leave the company as it was to temporarily lay off 800 employees for six months.

Why?

Economists and analysts provide several reasons why Yoon and Kang failed, but the same theme occurs throughout. They criticize the CEOs’ hubris leading them to manage their companies like chaebol do but without adequate capital and risk-management capability. “These salaried-employee-turned CEOs expanded as though they were chaebol,” says Hong Seong-guk, the head of KDB Daewoo Securities’ research center. “They had blind confidence in their success.”

Chung Sun-sup, the CEO of conglomerate analyzing firm Chaebul.com, shares a similar view to Hong’s. “Those corporations started to mimic chaebol once they reached a certain size, and I find the cause of their downfall there,” Chung says. “As they earn more money and have bigger assets, they could borrow more easily. They initially aspired to join the country’s 50 largest conglomerates and then the 30 largest. They wanted more and more and ended up entering the traditional industries dominated by chaebol,” Chung said.

Lee Man-woo, professor of management at Korea University, says, “They grew up in a short time and thought only about the days they were doing well, failing to slow down when they had to.”

One obvious problem in expanding like chaebol do is that they did not have enough capital to deal with a crisis. In addition to that, there were severe flaws in management and strategies. They entered the industries that were no longer growing; expanded in the industries not only dominated by chaebol but by global juggernauts; and borrowed in order to expand.

The first strategy that went wrong is unreasonable diversification of no-growth businesses through mergers and acquisitions. This is now plaguing not only Yoon of Woongjin and Kang of STX but also many Korean mid- and large-sized conglomerates, except Samsung Group and Hyundai Motor Group.

Jung Ku-hyun, the former chief of the Samsung Economic Research Institute and professor at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), says that the construction and shipbuilding industries that Woongjin and STX expanded into stopped growing a long time ago.

“Both industries were among the hardest hit during the 2008 financial crisis. Even other conglomerates such as Kumho Group and LIG Group went through difficulties because they tried to expand to the construction business,” said Chung.

What about Pantech, which stayed with its handset business? Analysts criticize Park for entering the realm of the industry dominated not just by Korea’s two major conglomerates, Samsung and LG, but also by global giants including Apple and Nokia. In fact, since Pantech’s earnings deteriorated, Nokia and Motorola collapsed and were acquired by Microsoft and Google, respectively, and Blackberry is looking for a new owner.

“Pantech was an original equipment manufacturer. When they were thriving, they even made money during the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. But they created their own brand, entering the industry already dominated by Samsung and LG. Pantech didn’t have enough capital,” said Chung of Chaebul.com. The same applies to STX, which tried to compete in the labor and-capital-intensive shipbuilding industry.

Furthermore, the downfall for Yoon and Kang is related to their obsession with ownership — a trait observed in chaebol — without the capability of protecting it. To have their conglomerates under their influence, they borrowed by printing bonds rather than issuing more shares and attracting external investors. Yoon had Woongjin Holdings issued commercial papers worth 119.8 billion won ($110 million) between July 31 and Aug. 2, 2012, without the capability of paying back the debt.

No more rags-to-riches billionaires?

Although poor management is responsible for the self-made CEO’s failures, the fact that they failed in the industries dominated by chaebol shows that no one can challenge the establishment of chaebol anymore. Some voice concern that Korea is no longer a country for self-made entrepreneurs.

The CEO Score, a conglomerate researcher, announced in September that, according to research results, the six eminent chaebol families — Samsung, Hyundai, LG, SK, Lotte and Hyosung — have grown immensely with their total assets doubling from 525 trillion won in 2007 to 1,054 trillion won. Economists say that this phenomenon is caused largely by the stalled growth of the Korean economy.

Lee Jong-woo, the research center chief of I’M Investment & Securities, says that chaebol that were already in business in the 1950s and 60s had many opportunities during the country’s growth, but the relatively young conglomerates’ performance depends on economic cycles and conditions of their industries rather than the long-term growth of the Korean economy.

“Rags to riches stories are now rare. There will no longer be a case like Kim Woo-choong,” Lee says. Kim is the founder and former chairman of Daewoo Group.

There are still a few self-made tycoons of large corporations including Park Hyeon-joo, chairman of Mirae Asset Financial Group and Gene Yoon, chairman and CEO of sportswear brand Fila. What should they bear in mind?

The first lesson from the failure of Kang and Yoon is that they should strengthen internal stability by “choosing and concentrating.” Chung of Chaebol.com says that Yoon, Kang and Park failed with choosing and concentrating. “The entrepreneurs should have abandoned their greed. It is important to figure out one’s strength and go strong for centuries with a focus on that,” Chung says.

Chung identified Samsung Group and Hyundai Motor Group as the companies that choose and concentrate well. Although the two conglomerates have been criticized for having numerous affiliates, the affiliates eventually support the core businesses of electronics and automobiles, respectively, he says.

Economists and analysts see relatively less risk in Mirae Asset and Fila, which have stayed in their industries. They were in the spotlight after Yoon, Kang and Park went down because their CEOs also started their careers as salaried employees. Lee says, don’t see that Park Hyeon-joo and Gene Yoon have big problems so far. Mirae Asset and Fila have built their base quite strongly.”

Chung expresses some doubt on both because they aggressively pursued M&As in the past few years. “Park and Yoon cooperated in acquiring Titleist. I am not sure yet if the acquisition was a good deal. The market will have to continue watching it. Furthermore, Mirae Asset is in the industry that is shrinking,” said Chung.

“Only big corporations are surviving, and the situation may get worse for Mirae. That’s why we talk about the co-existence of chaebol and non-chaebol. I think that is no longer possible.”

Jung, the KAIST professor, doesn’t agree with the notion of the end of rags to riches stories. He argues that entrepreneurs should look at the industries with high-growth potential. “New large corporations will come out from new growth industries such as information and communications technology. There are no longer growing industries within the manufacturing sector,” says Jung.

As examples of billionaires who came out of the new industries, Jung mentions Bill Gates of Microsoft, Larry Page and Sergey Brin of Google and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook.

The economist adds that various sources of funding such as venture capital and private equity other than borrowing from banks are now available to those with innovative, creative ideas.

Hong of KDB Daewoo Securities provides domestic examples including Naver, Nexon and Seoul Semiconductor, which are all set up by self-made entrepreneurs.

“The traditional industries are owned by the six largest chaebol families, but new industries can be still explored by non-chaebol. That’s why we need a creative economy. Don’t mimic chaebol, but concentrate on your strength. Naver didn’t enter the construction industry or own a golf course,” says Hong.

how is pantech doing now – they claim to have a goal of 10 trillion won in a couple of years?