The Dark Side of Fat Profit Margins

October 24, 2013 Leave a comment

The Dark Side of Fat Profit Margins

JUSTIN LAHART

Oct. 23, 2013 11:39 a.m. ET

It’s natural to worry about what might happen if companies’ extraordinarily high profit margins slip. The more troubling thought may be what happens if they don’t. Never before have American companies seen so much of their sales drift down to the bottom line. In 12 months that ended in the second quarter, U.S. after-tax corporate profits as a share of gross domestic product, a measure of profit margins across the entire economy, came to 10.9%, according to the Commerce Department. That was the highest level according to records going back to 1929. Nor are there signs of erosion: S&P Dow Jones Indices estimates profits at companies in the S&P 500 as a share of sales hit a high in the third quarter.It isn’t hard to find reasons why margins are so high. The share of sales going toward workers’ wages and benefits has declined precipitously. Companies have kept a tight lid on capital spending. Effective corporate tax rates have fallen. Interest rates are sharply lower.

Although such factors help explain why the environment has been so good, they leave unanswered an important question: Why aren’t historically wide profit margins getting competed away? One reason may be that there isn’t a lot of up-and-coming competition.

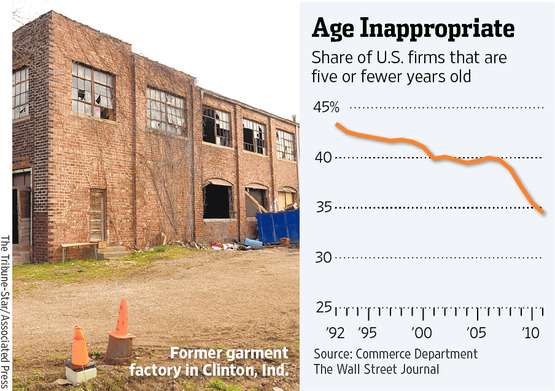

Even before the financial crisis struck in 2008, the environment for young firms appeared far less dynamic than in the 1990s. Back then, a hot market for initial public offerings created an easy environment for finding funding and a strong economy made it relatively easy to stay in business.

Since the recession, things have been moribund. In 2011—the last year for which there is data available—35% of firms operating in the U.S. were five years old or less, according to the Commerce Department. That compared with 40% in 2007.

Meanwhile, despite the well-publicized successes of a number of Silicon Valley companies, start-up activity remains muted. The Labor Department’s establishment birthrate, a proxy for the pace of new-business formation, last year matched the record low it plumbed in 2009.

To some extent, the dearth of young businesses reflects an environment in which keeping your day job seems wiser than starting something new. But in a lending environment in which funding for newer, smaller businesses is constrained, many would-be entrepreneurs are willing but not able. Facing fewer newcomers, established businesses have one less reason to spend more on wages and equipment; why put effort into building a moat that isn’t needed? This is great for profits but not the long-term health of the economy.

“One of the things we count on is this dynamism and competition we get from entering and expanding firms,” points out University of Maryland economist John Haltiwanger. New businesses have historically been the most important source of jobs, as well as a key driver of innovation. The fewer there are, the worse off the economy will be.

Fat profit margins are nice, for now. But a world in which companies don’t have to worry about their profits getting competed away is also one where investors can’t expect to fare well.