Top Jap Woman Bureaucrat Read 150 Books in Jail After False Charges; Fighter for justice

October 24, 2013 Leave a comment

Top Woman Bureaucrat Read 150 Books in Jail After False Charges

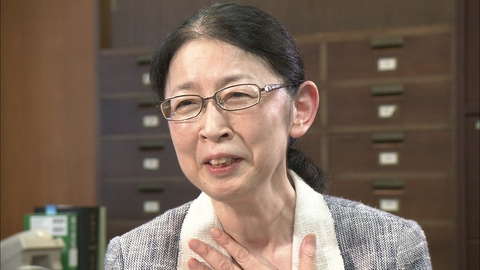

On Atsuko Muraki’s first day of work in Japan’s bureaucracy 35 years ago, she was given an assignment: help make tea each morning for the entire section of 20-30 people.Her response was to do it — and ask for more work. “I felt it couldn’t be helped,” Muraki said. “At the same time, I asked my manager not to go easy on me in terms of my main duties. He trained me properly.” Today, Muraki is administrative vice minister at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan’s most senior female bureaucrat and the second woman ever to reach that rank. Along the way she had to overcome not just discrimination but corruption charges that later proved to be false. During the investigation she spent five months in detention. The 57-year-old mother of two is a symbol of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s pledge to put women in 30 percent of leadership positions in Japan by 2020. Halting women’s tendency to drop out of the labor market in their 30s would release an untapped resource and bolster growth in the world’s third largest economy as the workforce shrinks, Abe says. He has cited the influence of Kathy Matsui, chief Japan equity strategist at Goldman Sachs. Matsui wrote in an update this year to her long-running “Womenomics” report that increasing female employment to match that of males would mean 8 million more people in the labor force and a gross domestic product as much as 14 percent higher.Best Option

“I wanted to work for my whole life,” the bespectacled Muraki said in her large, spare office at the ministry, where she hid a cheap plastic umbrella to keep it out of photographs. “It was important to me to find a workplace where I wouldn’t be discriminated against and where I wouldn’t be forced out if I married or had children. I thought the bureaucracy was the best option.”

She manages a staff of more than 30,000, with a budget of 29.4 trillion yen ($300 billion). Her ministry is charged with many of the most pressing issues facing Japan, from childcare to pensions and health care, whose costs are ballooning as the country ages.

Muraki worked her way up the ladder in roles mostly related to improving opportunities for women and the disabled. “In the past, people saw women as incapable of doing particular types of work, or of taking leadership roles,” she said, adding that the same stereotype targets disabled people.

Unlike Others

Yoshiaki Tajima, the director of Colony Unzen, a non-profit organization that provides services for the disabled, said Muraki’s rise to vice minister was a reflection of her talent. Muraki impressed him as different from other bureaucrats as soon as they met 15 years ago, he said in a phone interview.

“She was so eager to learn, when she had reached a position in the hierarchy where most people think they know it all,” he said. “She asked so many questions and she really seemed to enjoy her work.”

Born in the rural prefecture of Kochi, on the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, Muraki was so shy at school that she would go for months without speaking to the child at the next desk, she said in her 2011 memoir, “Never Give Up.” She graduated from a local university and joined the then-Labour Ministry — the forerunner of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — in 1978, partly because businesses didn’t at that time offer career opportunities for women. Japan’s Equal Employment Opportunities law took effect in 1986.

Serving Tea

The only person from her university to take the national bureaucracy’s career-track entrance exam, Muraki missed the window for interviews with ministries in Tokyo because she was unfamiliar with the recruitment process, she said in her book. She got one of her university professors to write a letter of introduction and persuaded the Labour Ministry to see her after other applicants had already received their job offers.

Muraki became one of 22 women among the 800 recruited under the bureaucracy’s career track for that year. On her first day at work she was informed that, as a woman, she would have to help a clerical assistant serve tea. Each of her colleagues had their own personal cup and she balanced them on a tray to deliver them to each desk, taking the opportunity to try to get to know her co-workers.

Life as a female bureaucrat has changed remarkably over the span of her career, Muraki said: “When I joined, section managers would refuse to take the female new hires. About 10 years later they would say, ‘A capable woman is preferable to a completely incompetent man.’ Now they say, ‘Whichever. Just give us the most able people.’”

Dropping Out

Nevertheless, Abe is far from reaching his goal for female management. A report distributed this month by Minister of State for Gender Equality Masako Mori shows that while about a quarter of career-track recruits to the bureaucracy are female, only 2.6 percent of posts from section chief upward are held by women.

The pattern holds across other sectors. Just two members of Abe’s 19-strong cabinet are female and a fresh lineup of 25 political vice-ministers unveiled last month included only four women. Women make up 15 percent of department managers across all sectors, according to the health ministry.

The first woman to reach the peak of the bureaucracy was Nobuko Matsubara, who was appointed in 1997 to the top job at the then-Labour ministry. She later became an ambassador to Italy.

“Women’s pay is now about 70 percent that of men,” Muraki said in a speech to the Brookings Institution in Washington last month. “The main reasons for this are that they give up work part-way through their careers and that they are not promoted.”

Government measures to provide more childcare should improve the situation, she said, adding that she encourages younger female colleagues not to “run away” from chances for advancement.

Late Nights

Muraki struggled with the long hours required of Japanese bureaucrats while raising her two daughters and said she thought about quitting in her 30s when her elder daughter fell sick.

“It was difficult when I had to go home early while my male subordinates were still working late into the night,” she said. “When I say early, I mean 10 p.m.”

Her daughters say they saw little of her when they were growing up. “Even so, I knew she cared about me in her own way,” said the elder daughter in an essay in Muraki’s book, to which she didn’t attach her name. “She made recordings of herself talking to me and I would go to sleep listening to them every night.”

Muraki entered the public eye in 2009 when she was arrested and charged with falsely certifying an organization as representing disabled people so that it could claim cheaper postage rates. While detained, she used the unfamiliar free time to read 150 books.

Prosecutor Jailed

She was released and subsequently found not guilty in 2010 at a trial in which a subordinate testified that he had created the false certification alone.

A prosecutor was later jailed for 18 months for tampering with evidence and Muraki won 37.7 million yen in compensation from the government, according to her lawyer, Junichiro Hironaka. Muraki donated the money, minus trial expenses, to set up a foundation supporting disabled people who fall afoul of the law.

“I don’t know, I can only imagine,” Hironaka said when asked why his client had been targeted in the case. Allegations that she had been acting at the behest of opposition Democratic Party of Japan lawmaker Hajime Ishii could have been intended to undermine the party, he said. At the time, it stood on the verge of taking power from the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

Vindicated and restored to her position at the ministry, Muraki was promoted to vice minister in July. She has attracted some criticism, according to former LDP lawmaker Yoichi Masuzoe, who was health minister when she was arrested.

Husband’s Help

“I’m a great supporter of hers,” Masuzoe said in a phone interview. “But I don’t like the way she appears to have been used for political purposes. By appointing a popular figure for whom people feel sympathy over the false charges, the Abe cabinet can maintain its popularity.”

In her Washington speech, Muraki hailed her fellow-bureaucrat husband, Taro, for being around to cook and do laundry, at a time when it was highly unusual for Japanese men to be involved in such tasks.

“I spoke to her husband while she was in detention and commented that it must be hard for him to deal with all the housework on his own,” said lawyer Hironaka. “He told me it was no problem because he’d always done all the housework. He’s an elite bureaucrat too, but he supported her in that way.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Isabel Reynolds in Tokyo at ireynolds1@bloomberg.net

Fighter for justice

BY TOMOKO OTAKE

MAY 1, 2011

Atsuko Muraki was thrown into the public spotlight in 2009, when she was head of the Equal Employment, Children and Families Bureau at the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry.

Back then, Japan’s major news media suddenly started casting her as a lead perpetrator in a fraud allegation involving Tokyo-based Rin-no-kai, an organization that had improperly acquired government accreditation as a group working for the disabled in order to use a postage discount system available for such entities.

Muraki had never heard of Rin-no-kai, nor had she had any dealings with other suspects who had been linked to the group, but that didn’t stop the media — fed daily with leaks from prosecutors — from stalking her.

“The approaches from the mass media were so fierce that I couldn’t work at my ministry desk or go home,” Muraki recalled in an interview published in the monthly Bungei Shunju magazine in October 2010. “Reporters were staked out in front of my apartment building, and sometimes sneaked inside the security entrance in order to approach me.”

Then in June 2009, Muraki was arrested by the Osaka Public Prosecutors Office, put into solitary confinement and questioned for 20 days. After that period of interrogation, she was denied bail and detained for more than four months.

In many criminal cases in Japan, suspects subjected to such treatment own up to wrongdoings at this stage — even if they haven’t committed any offense. Often that is because they fear they might never be released from detention if they don’t confess. Investigators also try to sweet-talk suspects, telling them they will receive a lighter sentence if they admit to what they are being accused of.

But Muraki resisted the pressures and maintained her insistence that she had played no role in the Rin-no-kai postage scam. Nonetheless, a month after her arrest she was charged with instructing a junior ministry employee, Tsutomu Kamimura, to create a certificate for the group.

Then, in court, Kamimura retracted a confession he’d made in which he implicated Muraki and admitted that he had issued the official accreditation of his own volition.

He also said that he had been coerced by the investigators to go along with their story involving Muraki, and testified that prosecutors had completely fabricated Muraki’s involvement in the case.

Though to this day prosecutors’ motives have not been fully explained, the extent to which they cooked things up was quite amazing. It afterward emerged that they made up “secret” conversations, meetings and other exchanges between Muraki, Kamimura and others they brought into the case as alleged conspirators. They even tampered with “hard evidence” on one of Kamimura’s floppy disks to make the timing of the alleged crime fit their scenario.

As these and other details of the complex frame-up unraveled in court, the affair developed into one of the biggest scandals in the history of Japan’s postwar judicial system.

Muraki was finally acquitted in September 2010, and just last month the Osaka District Court sentenced Tsunehiko Maeda, the lead prosecutor in the postage fraud case — who had admitted to altering the floppy disk data — to 18 months in prison.

Throughout Muraki’s ordeal prior to her court victory, many who believed in her innocence threw their support behind her from the beginning — including those who knew her through her work helping people with disabilities.

Among those was Yoichi Masuzoe, the then-health and labor minister, who broke away from the norm when asked for comment on her arrest. Instead of apologizing because a member of his ministry staff had “caused a problem,” which is the protocol for such officials faced with scandals involving their organizations, Masuzoe described Muraki as “a highly competent bureau chief and the shining star for other working women.”

What does Muraki think about it all now? Sitting at her desk in the Cabinet Office, where she was posted soon after her acquittal, and where she now works as the director-general of Policies on Cohesive Society, the 55-year-old native of Kochi Prefecture in Shikoku recalled that terrible time in her life, as well as her young days as a bookworm, her struggles as a working woman and mother, her lifelong passion for policies aiding those with disabilities, and much more.

This transcript of an hourlong interview reveals how a hard-working and well-respected bureaucrat motivated by noble aspirations to make people’s lives better, fell victim to a malicious criminal investigation. It also demonstrates how this society’s failed systems still leave ample room for innocent citizens to be tried for crimes with which they have no connection whatsoever — and how their lives can be irreversibly changed thereafter.

I understand that you grew up in Kochi Prefecture. What kind of child were you?

I used to cry a lot.

Really? In what kind of situation?

All the time. I wonder why … (but) I remember crying a lot. Before entering elementary school, I was bullied a lot. One day I decided to resist, thinking the group of bullies couldn’t understand the feelings of those they bullied. My revolt succeeded, and we all ended up becoming friends. From that time on, I cried less. But I was extremely shy. I was not an outgoing type. I would be one of those who would hide behind their mother, clinging to her clothes.

That’s really surprising.

Yes. Maybe it got a little better after I started working.

You attended a local high school and then went to study at Kochi University’s Economics Department. What was the main focus of your study?

I mainly studied public-sector economics and public finance.

What did you do when you weren’t studying at college?

I was either working at part-time jobs or reading books.

What kind of books did you read?

Nothing to brag about (laugh). From early on, I had been interested in animal research, so I started with works by (French entomologist Jean-Henri Casimir) Fabre and (wildlife writer Ernest Thompson) Seton. I then moved on to (Austrian zoologist) Konrad Lorenz and all these other people. I also like mystery novels, including the Sherlock Holmes series (by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle), and Ellery Queen, Agatha Christie, etc. Then at college I started reading Japanese mystery writers, including Bin Konno and Miyuki Miyabe. I like Michael Connelly, too.

After you graduated from Kochi University you passed the exam for top-tier central government bureaucrats. Why did you decide to become a bureaucrat?

My biggest reason back then was that in Kochi there wasn’t a single private-sector company that would hire female four-year college graduates.

That’s shocking.

Well, I come from the generation before the Kinto-ho (the Equal Employment Opportunities Law of 1985, which, for the first time in Japan, banned sexual discrimination in the hiring of workers). They hired female graduates of junior (two-year) colleges, but not four-year university grads. At that time, too, women were still pretty much forced to leave their jobs after marriage or childbirth.

The only fields in which women were not forced to leave their jobs halfway through their careers were teaching or public service. I wanted to work for life, so I applied for jobs with the central government and the Kochi prefectural government, hoping either one would come through. Also, because I had studied public-sector economics, and because my father was a labor and social security attorney, I was somewhat familiar with labor issues.

I remember hearing that you have always taken to heart something your college professor told you, which was that “a public servant’s job is to translate people’s needs into laws and policies.” Is it true that this has left a lasting impression on you?

Yes, though it’s not that those words made me choose to become a public servant. The teacher said that as his parting words for. Even today, I often remember that and it has been something I have believed in all these years.

The word “translate” remains such a key idea for me, 33 years on, as it shows precisely that it is the users of policies and laws, not bureaucrats, who play the lead role — and that policies and laws must be born of interaction between us and residents or citizens.

When you got a job with the then-Labor Ministry, were there other female career bureaucrats?

Well, the year I joined, about 800 new hires for all the central government ministries got together at Tokyo’s Yoyogi Gymnasium for the orientation. I was one of just 22 female hires. That shows what a minority we were.

Is it true that, the day before you joined the ministry, a big debate erupted in the section you were to join — over whether you should serve tea to other employees in the section?

I learned about it on the first day of my work at the ministry. My immediate boss told me then, “Well, there was this huge argument yesterday, and the people in the section were split in half. But in the end, I’m sorry to say we decided to make you serve tea.” I said “Fine.” That was because, when I applied earlier to the Kochi Prefectural Government, an official explained to me that duties for “female prefectural government employees” are such and such. I thought, “Hmm. Why categorize female and non-female workers?” After all, we all took and passed the same exam, which was the top-tier bureaucrats exam. … I then realized what it is like for a woman to work in the bureaucracy.

Another thing was that there was a non-career-track, older woman at the ministry, and before I joined she was doing all the tea-serving duty for the section by herself. If I joined, we would divide the duties between the two of us, but if I didn’t, she would have been forced to keep serving tea by herself. So I said OK, and over time, little by little, I’d won my supporters.

You must have done a lot of overtime, I suppose.

Yes. At my peak I would finish work at around 2 a.m. and then go home. Then I would go to the office the following morning as usual. I learned how to sleep on the train, clutching the strap.

I understand you married a fellow labor ministry employee, Taro, when you were in your fourth year there. And you gave birth to two girls.

Yes, I gave birth to our first girl when I was 29 years old and then our second girl when I was 35.

How were you able to juggle parenting and work when you were so busy at work?

When I got pregnant with my first daughter, I was transferred to a less busy section. At that time no nurseries would take care of babies less than 1 year old, so I placed my daughter in the care of so-called hoikumama (“nursery mums,” who take care of children in their homes). Mine would be available until 10 p.m., but then after about two years I was transferred to the countryside — where I didn’t have to work until late at night.

Were you torn between feelings of guilt as both a parent and a boss?

I felt I was not in a position to say strong things to my subordinates (who were all single men) but I didn’t feel guilty toward my children. I happen to think I have been a good mother. I’ve always thought that we are all in this together — me, my husband and my daughters — and that we are like comrades — except that I always I wanted to work in a more normal way. Also, when I needed to I took a cab home to save 30 minutes out of my one-hour commute, thinking that I was buying time.

You have been involved in creating new policies for people with disabilities, and have said that work in this field has been rewarding. Why is that in particular?

Well, there are several reasons. For one thing, people with disabilities are much more employable than those who don’t know them think they are. I noticed this because I had worked with policies for women before. Many people were seriously saying that women aren’t born for management or sales jobs. However, women weren’t even given a chance or enough training in society to become adept at such lines of work.

Today, sales is something that women are considered to be most suitable for. It was because of the social environment, prejudice from others and a lack of confidence on the part of the women themselves that they weren’t working in those areas. I felt the same way about disabled people. I wanted to prove that people with disabilities can work.

Also, companies who hire disabled people, welfare facility employees and teachers at schools for these people are so hard-working, full of vitality and warm-hearted. My job was to create policies that would help these people, who would then help the people with disabilities. That I found very interesting.

Well, then, you were embroiled in a criminal case from which you were exonerated later. Now everyone knows that the charge against you was completely absurd. But back then, the media assaults on you were quite extraordinary.

Yes, it was incredible.

What was the toughest aspect of the ordeal?

Well, when I found myself at the center of the case, the first thing I thought was that my family would be with me 200 percent. And then one or two days later, I started getting messages of support from people who knew me through work. So I learned that people who’d dealt with me directly in the past would believe me. Consequently, no matter what people in society thought of me, I was confident that I hadn’t lost their trust.

On the other hand, that alone didn’t mean I would be acquitted. No matter how hard I tried to prove my innocence, and no matter how right I was, it didn’t guarantee my acquittal. I found a sort of absurdity in the fact that my fate hinged on someone else’s judgment — that was hard.

Fortunately, the case didn’t cause my family any trouble, at my children’s schools or in our relationship with neighbors or at our workplaces. It’s only through our relationship with the prosecution and the mass media that we suffered (laugh).

I was worried, though, that unless my innocence was proven in court, I would make my supporters’ credibility compromised. That was a huge pressure. I felt that I would really have to win the case.

Is it true that you read 150 books in the five months you were in detention? That means roughly a book a day, which is a lot of reading!

Yes. The first 20 days in detention were very taxing, as I was being interrogated by investigators and I was under enormous pressure. The last thing you want to do is to dwell on the case (they are presenting). I thought that if I gave in to the pressure and felt down, the fight would be over. I had made up my mind never to feel down. I was set on having a change of mood, so I turned to the books. From the time I woke up in the morning I would start reading.

Then, after the 20-day interrogation period, there was really little to do. So every morning I would get up, fold my futon (in my solitary cell) and do a little bit of cleaning, then I’d have breakfast and, later, lunch and dinner. We also had simple exercise sessions in the morning and afternoon, time for a bath and, two or three times a week, we had time to do some exercise outside. And I had meetings with lawyers, family and friends.

Even with all that, though, I had about five to eight hours as free time every day, so I used 100 percent of that spare time to read. I kept reading books until the very moment they switched off the lights.

Looking back, why do you think that you — of all the elite bureaucrats at the ministry — were targeted by the prosecution?

I honestly don’t know. I wanted the prosecutors to make that clear to me in their post-trial review, but they didn’t. I can only imagine why the document that (Rin-no-kai) group got from the ministry had my name on it. The group probably claimed that they got the document from me (to show it was authentic). Also, of all the bureaucrats involved in the case, I was the highest-ranking official. I don’t know whether this is true or not, but now many people say (the prosecutors) were driven by their own ambition to go after the highest-ranking bureaucrat (working in that area). But I don’t know why, or on what basis, they decided to press charges against me. It is still a big mystery.

Your case has stirred a big debate on the many ills of the prosecution system in Japan. What do you think is the biggest problem?

The fact that interrogation reports are highly valued, and the ways in which trials revolve around those reports, I would say. Because interrogation reports are treated as highly incriminatory evidence, it is only natural that prosecutors would go out of their way to create interrogation reports that would fit their scenario. I think that is at the bottom of all the problems.

Do you think the videotaping of the entire interrogation process (which has been called for to prevent false accusations) is necessary to change that?

Yes, but more fundamentally, the trials should not rely on interrogation reports, but instead use objective evidence and court testimony. The (recently introduced) lay-judge system has helped to shift the focus of criminal cases to trials, which are open to the public and where all the testimonies are cross-examined. In my case, judges asked very detailed questions. So if you examine the witnesses from all sides, lies will be revealed.

And trials should place more emphasis on objective evidence. Currently, all the evidence is in the hands of prosecutors, who hide that which won’t help their case. In my case, I was interrogated for 20 days, but other defendants have seen their detention periods extended to 40 or 60 days because prosecutors break up the charges into two or three separate sub-charges. Many people have given up during that process, thinking that, if they don’t admit to the charges, they will never be released from detention. That’s how they have resignedly signed reports that they don’t agree with. Such a system should be drastically changed.

I suppose you have seen many ills in the mass media as well… (Laugh)

How do you now view the media, based on your dealings with them?

Well, for one thing, as I was stalked by the media in exactly the same way celebrities are on TV, I felt their reporting style itself was quite violent. They came knocking on my door at home and chased me around everywhere. They also shoved microphones at me and said, “You have been accused of this and that. What do you think?” I often wondered, “It is actually only you guys who are accusing me. Who else is saying this and that?”

It was quite interesting. I guess that everything in the media started from leaks they got from the prosecutors (before the trial). The newspapers wrote the stories, treating leaked information as facts. Then they came to me and asked me what I thought about things I had had absolutely no role in. I found myself unable to comment, as I could not deny the possibility that my ministry as an organization could have been involved. Also, they were asking me about something that took place five years before.

Secondly, I knew very well that the media would be hard-pressed not to publish information they got from the prosecutors, but I also wondered if that was all they needed to do. They could have written in a more restrained manner, bearing in mind that it was one-sided information.

If you read the fine print, you can tell the media are fulfilling their minimal requirement of saying that the story is “according to the prosecution’s scenario,” but if you just read the headline, or if you read what they are emphasizing in the article, it is far from being balanced.

Also, I was intrigued by the way all the newspapers were so similar in their tone of reporting — and then they all suddenly changed completely (and treated me as a victim) at exactly the same time.

Did newspaper reporters apologize to you at some point?

Well, as my ruling drew closer, and right after the ruling, the reporters knew they couldn’t start asking questions until they apologized first. They all said they would write articles reviewing their coverage of the case, and they did have such articles in the papers. But to be honest, I think the same kind of thing would happen again in some other case.

Another thing that I found interesting was, I kept asking journalists who came to me when it was that they started to question the prosecution’s story. They all had different moments. Some pointed to the testimony of the section chief (Kamimura, who claimed in court his confessions were coerced by prosecutors), and others pointed to incidents even before that. But the more experience reporting on prosecutors they had, the earlier they noticed that something was wrong. It still took them a long time to reverse the tone of their coverage, though. They had probably got other tips that made them question the prosecution, but they hadn’t extensively followed them up — because they don’t want to confront the prosecutors. Many had thought the case was dodgy, but in the face of a prosecution that is so confident and sticking to their scenario right to the end, it took the media so much courage to break away.

You filed a damages lawsuit in December 2010 against the central government and three prosecutors who had investigated your case. But you are still a government employee yourself. Did you waver at all over suing the government?

Yes. I didn’t want to do it if I could have avoided it. My bosses have been very understanding. I consulted with the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry and the Cabinet Office. They both said, “Do what you have to do — calmly.”

Really?

Yes. I said, “I’m in a delicate position, but I want to proceed with my suit.” Then the two said exactly the same thing. I was like, “Wow.”

In fact I was waiting until the Supreme Public Prosecutors Office came out (in December) with its report reviewing the case. But it was such an (insufficient) report, so I felt that I couldn’t let others seek justice for me. The people in the prosecution who were arrested or punished this time were only those involved in tampering with evidence in the seized floppy disk. But the arrests and indictments (over the postal fraud case) are not just about the floppy disk.

After I read the Supreme Public Prosecutors Office report, I talked to my lawyer and said I must file my suit. I have my feelings about how certain kinds of people should not be prosecutors, and how this type of interrogation should never be repeated.

Apart from winning damages and punishing those people, I want to get the truth out and let the public know — so my case can work as a deterrent. A part of me also thinks that I want to get this behind me and move on, but after a lot of wavering I decided that I still had unfinished business.

What do you want to dig out as the truth? Is it why the prosecution fabricated your involvement in a crime?

Well yes. Or rather, the prosecution still says it had enough reason to suspect wrongdoing (by me), and that it wasn’t a frame-up. It really depends on the definition of frame-up, but if they had investigated in normal ways they wouldn’t have prosecuted me like that. I want to at least expose this to society at large. I can’t take their excuse for an answer.

Right after your acquittal you were reinstated as a bureaucrat, and have been assigned your current new job. What do you want to accomplish at the Cabinet Office?

I guess my jurisdiction mainly includes measures for children and people with disability — and anti-suicide measures. I’m also in charge of policies for a “cohesive society.” A cohesive society means a society in which all kinds of people with various strengths and shortcomings can help each other, where people with handicaps are not excluded, and where we can all rely on one another. And I think at the root of such a society is a shared understanding that people who can work, do work, and that we help each other out. My goal is to present a vision of such a society.

When we talk about social security, we talk about pensions, health care and nursing care separately, but there must be a vision that ties each of these social security systems together. I see my job as being to present such a vision — with social cohesiveness as an underlying theme.