Indian Banks Head Out to the Country; India’s largest private-sector banks are ramping up their rural networks, building hundreds of backwater branches as a slowing Indian economy squeezes business in the cities. “We are not like a biscuit company that sells you something, you eat it, burp and the work is done”

October 25, 2013 Leave a comment

Indian Banks Head Out to the Country

NUPUR ACHARYA

Updated Oct. 24, 2013 5:10 p.m. ET

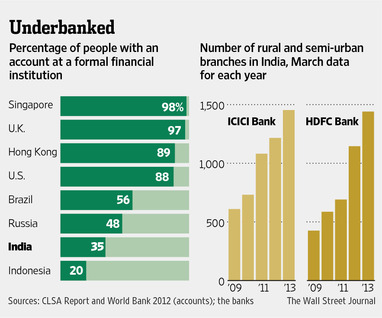

CHOMU, India—Until last year, Anita Yogi had never had a bank account. She would stash what little savings she had around the house. Today, the 26-year-old seamstress from this village in the northwest state of Rajasthan has a new account and a small loan for materials to make saris, the traditional, draped garment worn by women in India. “Now I want to expand my business and save more for my children’s educations,” Ms. Yogi said, showing off her new automated-teller-machine card from HDFC Bank Ltd.500180.BY +1.38% India’s largest private-sector banks are ramping up their rural networks, building hundreds of backwater branches as a slowing Indian economy squeezes business in the cities. Bankers say operations in small towns and villages are booming because they are capturing first-time savers and borrowers in pockets of the country that were previously ignored. This group of customers—and there are hundreds of millions of them in India—is set to be the next big opportunity for the country’s banking industry, which already has a total loan book of close to $1 trillion, according to the Reserve Bank of India, the country’s central bank.“No bank, existing or new, can afford to ignore this market,” said Chanda Kochhar, chief executive of ICICI Bank Ltd. 532174.BY -0.47% , India’s largest, private-sector lender in terms of assets.

The Reserve Bank of India has made it easier—fewer restrictions and regulations, less paperwork—to open branches in rural areas because it wants to encourage lending to the farmers and small businesses there.

While the costs of reaching rural areas can be high, banks say it is worth it as they start long-term relationships with customers who will need an increasing amount of banking services, including, eventually, insurance and mutual funds.

Banks also are targeting the rural borrowers for loans, for which they charge a higher rate than in the city.

In the past 18 months, ICICI has more than doubled its rural network to 656 branches, close to a fifth of its total of 3,384 branches. Almost all the new branches are in villages that were previously unserved by any bank, Ms. Kochhar said.

While India’s state banks have long been required to maintain extensive networks of rural branches, the private sector’s increased focus on the less-populated corners of the country is a new avenue for the country’s unbanked to join the formal financial system.

Today, just 35% of Indians have a bank account, according to the World Bank, partly because there aren’t enough banks to serve the country’s 1.2 billion people.

As rising incomes and spreading bank networks allow more Indians to open their first bank accounts and take their first bank loans, the market will grow.

CLSA Ltd. estimates bank lending in rural areas will climb to close to $900 billion, or around a third of the nation’s total loan book, by 2020. Last year, rural lending totaled $170 billion and represented only 20% of the country’s total loan book.

HDFC Bank, India’s second-largest private-sector bank by assets, reached a tipping point this year. It now has more than half of its branches in rural and semiurban areas. Only a year ago, the smaller towns only accounted for a third of its branches.

This big opportunity, however, is fraught with challenges. The cost of operating a branch in the rural areas is high relative to the value of the business it generates. Transactions are small, and there usually is little or no credit history for new borrowers.

To overcome the cost hurdles, ICICI Bank has opted for one-car-garage-size branches that hold little more than a teller, manager, laptop and small safe. In less populated areas, the village bankers will rotate between two branches, staffing one in the morning and a different one in the afternoon.

ICICI also runs roaming branches. The branches are built into a van, which carries everything needed to do basic banking, including a teller, money-counting machine, ATM and an armed guard. It stops in four villages a day.

Chhote Lal Meena is a manager for two tiny ICICI branches in the villages of Rajasthan. When he arrives at his morning branch in the village of Khatwa on his motorcycle, most mornings there already are people waiting for it to open. At noon, he closes that branch, has lunch and then moves on to his other branch in a village called Deoli.

“We get about 15 to 20 customers daily for cash transactions,” Mr. Meena said. “But on days, when the government benefit money comes in, that number can go up to 50 to 100.”

Government handouts are giving villagers incentives to open bank accounts for the first time as increasingly the government subsidies for food, employment, fuel or fertilizer programs are paid directly into the accounts of the needy.

ICICI Bank is holding camps and distributing comic books to teach potential new account holders how to qualify for the government programs and set up the bank accounts they need to receive government money. In the past two years, ICICI Bank, which is listed in New York as well as India, says it has transferred more than 14 billion rupees ($206 million) of subsidies through its new accounts.

HDFC Bank managing director Aditya Purirecently trekked to the small town of Chomu to let people know his bank was ready for more rural business.

HDFC already has brought more than two million never-banked families into the financial system, he said, and HDFC is dug in for the long run with its small branches in dusty towns. It plans to add a further 10 million unbanked families in the next five years.

“We are not like a biscuit company that sells you something, you eat it, burp and the work is done,” he said.