Puerto Rico: Greece in the Caribbean; Stuck with a real debt crisis in its back yard, America can learn from Europe’s Aegean follies; Puerto Rico’s debt crisis: Puerto Pobre; A heavily indebted island weighs on America’s municipal-bond market

October 25, 2013 Leave a comment

Puerto Rico: Greece in the Caribbean; Stuck with a real debt crisis in its back yard, America can learn from Europe’s Aegean follies

Oct 26th 2013 |From the print edition

IT WILL not be long till Congress and the White House start squabbling again about the budget in Washington, DC. But before they create another artificial debt crisis, Barack Obama and his Republican opponents ought to pay some attention to a real one 1,500 miles to their south-east. Puerto Rico, an American territory, risks a Greek-style bust. With $70 billion of debt outstanding, the equivalent of 70% of its GDP, it is more indebted than any of America’s 50 states. (Puerto Rico is not technically a state, but its bonds are treated as if it were.) Yields on its bonds have soared as high as 10%, as investors fret it may be heading for a default.Like Greece, Puerto Rico is a chronically uncompetitive place locked in a currency union with a richer, more productive neighbour. The island’s economy is also dominated by a vast, inefficient near-Athenian public sector. And, as with Greece, there are fears that a chaotic default could precipitate a far bigger crisis by driving away investors, and pushing up borrowing costs in America’s near-$4-trillion market for state and local bonds. Yet the Hellenic comparison is also helpful: it should show the Americans what not to do.

For decades Puerto Rico has been sustained by federal subsidies. Its people, far poorer than the American average, get lots of transfers, from pensions to food stamps. Until 2006 the economy was buoyed by tax incentives for American firms that manufactured there. As drug companies took advantage, the territory became a vast medicinal maquiladora.

This tax break disappeared in 2006, and Puerto Rico’s economy has shrunk virtually every year since. It has been able to keep on borrowing, thanks to another subsidy: interest on Puerto Rican debt is exempt from state, local and federal taxes in America, making it artificially attractive to investors.

Some Puerto Rican bonds that are just dyin’ to meet you

No growth and heavy debt are a toxic combination. In 2010 Puerto Rico’s previous governor tried—and failed—to boost the economy with tax cuts. The current one, Alejandro Padilla, has raised taxes sharply, and hopes for a balanced budget in 2016 (see article). Puerto Rican officials insist their country is solvent. And with some heroic assumptions about future growth and rising tax revenue, you can get the numbers to add up.

This is where Greece’s experience warrants study. It suggests that austerity alone is no route to solvency in a chronically uncompetitive economy. Puerto Rico’s priority should be structural reforms to boost growth, from breaking up monopolies to reducing red tape. The island scores 41st in the World Bank’s Doing Business index, whereas America is fourth. Labour costs are too high, not least because the federal minimum wage, which applies in Puerto Rico, is almost as much as the average wage. Politicians in Washington must help, not least by getting rid of crazy rules that force all cargo between the island and American ports to be carried on American ships.

The second lesson from Greece is that if debt does need to be restructured, it is best to do it sooner rather than later. Greece waited far too long. America’s Congress is unlikely to provide official loans to pay off private bondholders, as the Europeans did for Greece. But America’s policymakers could, and should, ensure that a Puerto Rican debt restructuring is orderly. The federal government could provide interim finance to assist the restructuring, much as the IMF does elsewhere. Even the legal details of Greece’s bond swap could be a model.

None of this would be easy even if policymakers in San Juan and Washington were bold and far-sighted. But the former are pussyfooting, and the latter are not even paying attention. Expect Puerto Rico’s debt crisis to get worse.

Puerto Rico’s debt crisis: Puerto Pobre; A heavily indebted island weighs on America’s municipal-bond market

Oct 26th 2013 | WASHINGTON, DC |From the print edition

ALTHOUGH investors are now less jittery about a possible default by the American Treasury, they are rightly still nervous about a drama unfolding in the market for state and local debt. Since May, yields on bonds issued by Puerto Rico, a self-governing American territory, have shot up to between 8% and 10%, despite their (barely) investment-grade rating and tax-exempt interest.

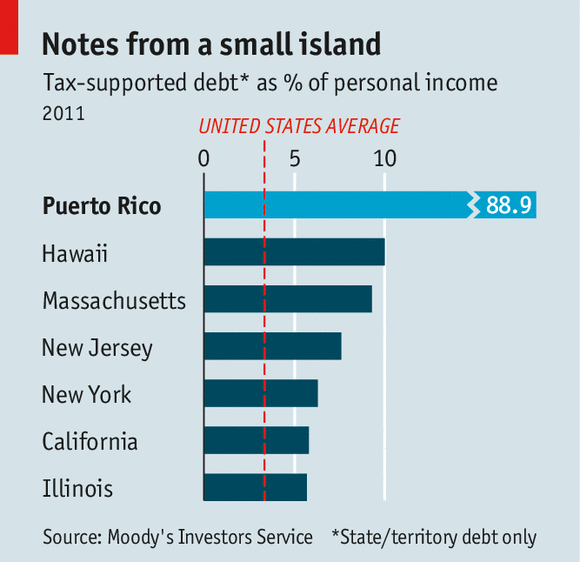

Puerto Rico carries outsized importance in America’s almost $4 trillion municipal-debt market, which includes bonds issued by states and other local authorities as well as by cities. The island’s current debt, between $52 billion and $70 billion (depending on how it is measured), is the third-largest behind California’s and New York’s, despite a far smaller and poorer population. In America’s 50 states the average ratio of state debt to personal income is 3.4%. Moody’s, a ratings agency, puts Puerto Rico’s tax-supported debt at an eye-watering 89% (see chart).

Puerto Rico’s debt has long been a staple of American municipal-bond funds because of its high yields and its exemption from federal and local taxes—of particular appeal to investors in high-tax states. That let Puerto Rico keep borrowing despite its shaky economic and financial condition, until Detroit’s bankruptcy in July alerted investors to the threat of default by other governments in similar penury.

America won control of Puerto Rico in the Spanish-American war of 1898. Its people have American citizenship and receive American government pensions, but pay no federal tax on their local income.

The economy has big structural problems. Participation in the labour force, at 41%, is some 20 percentage points below America’s. The island has the federal minimum wage, even though local productivity and incomes are far lower than in the rest of America, creating a strong disincentive to hire. Inflated benefit payments, for disability for instance, discourage work. Moody’s Analytics reckons the territory’s bloated public sector accounts for 20% of employment, compared with 3.7% for the average state (though it provides some services that the federal government would on the mainland). Growth and investment are hampered by bureaucracy, stunted infrastructure and crime.

Shrinking, sinking

Puerto Rico has been in recession virtually since 2006, when a federal tax break for corporate income expired, prompting many businesses to leave. As Puerto Ricans with prospects emigrate, the remaining population has aged and shrunk. The government has run budget deficits (prohibited for states) for the past decade, averaging 2.5% of GDP from 2009 to 2012. Its pension fund is only 7% funded, which is abysmal even by the standards of other American states and territories.

The current administration has sought to shore up its finances by increasing taxes by $1.1 billion (about 1% of GDP) and raising the retirement age for government employees, as well as the share of their salaries they contribute to their pensions. It has promised to wipe out its budget deficit, projected at $820m this fiscal year, by 2016.

Such austerity could further hobble growth, making it harder to shrink debt ratios. Luis Fortuño, the previous governor, lost his job last year partly because of public anger at the cuts he oversaw. Like Greece in the euro zone, Puerto Rico has no control over monetary policy (the preserve of the Federal Reserve), and so cannot mitigate a fiscal tightening with lower interest rates or a cheaper currency.

Investors meanwhile are so wary, after years of missed deficit targets, tardy financial reports and accounts opaquer than those of other states, that Puerto Rico has had to cut back on new bond issues. It is filling the gap with more short–term bank loans; but they come at punitive rates of interest and must be rolled over more often.

Investors are now openly debating whether Puerto Rico will default. Its constitution requires that its general-obligation bonds ($10.6 billion of the total) get first claim on tax revenues. Other bonds are backed by dedicated revenue such as sales tax and power bills and by a law authorising the government to pay interest ahead of other claims. “Honouring debts is not only a constitutional but also a moral obligation,” Alejandro Padilla, the governor, told investors earlier this month.

Yet politically it may be tough to gratify bondholders if police, doctors and teachers go unpaid. The federal government cannot be counted on for a bail-out: fiscal hawks in Congress would almost certainly balk at the expense and the precedent.

Should Puerto Rico seek to restructure its debts, it would be entering uncharted legal terrain. Unlike a city it cannot declare bankruptcy. It does not enjoy the same sovereignty the constitution grants the states; should it try to renege on its debts, Congress might intervene. Years of litigation would follow.

Puerto Rico’s problems have not yet had much effect beyond its shores. Its debt is held mainly by mutual funds and individuals, although in recent months many have sold to distressed-debt specialists. Some brokers have stopped selling its bonds to their clients. Borrowing costs have risen for a few highly indebted states such as Illinois, but the majority have no trouble selling bonds, says Chris Mier of Loop Capital Markets, which specialises in municipal debt. Happily, state finances are much healthier today than in 2010. But complacency would not be wise. No state has defaulted since 1933. A default by Puerto Rico could come as a wake-up call.