@Cicero Would Have Loved Twitter: In many ways, Facebook and Twitter are a throwback to ancient modes of sharing news.

October 28, 2013 Leave a comment

@Cicero Would Have Loved Twitter: In many ways, Facebook and Twitter are a throwback to ancient modes of sharing news.

L. GORDON CROVITZ

Oct. 27, 2013 5:40 p.m. ET

‘You cannot get to the end of the Internet,” said author Tom Standage when asked what role is left for traditional news publishers. He said there is an element of “finishability” in newspapers and magazines, whether in print or online, that many people value in an era of information overload. Otherwise, Mr. Standage, a leading student of the history of technology and its portents for the future, had little good news to offer the news business during a discussion last week about his latest book.In the 1990s, Mr. Standage wrote the dot-com cult classic “The Victorian Internet,” comparing the Internet to the telegraph, which had a huge impact in the 19th century. In his new book, “Writing on the Wall,” he says the era of top-down communication dominated by print publishers and broadcasters will turn out to be a brief exception to the historic rule that social media are the main way in which people get and share information.

Most adult Americans are on Facebook, FB -0.94% and for many people Twitter is the preferred way to share news. Last week the Pew Research Center and Knight Foundation released a report finding that many people prefer to have news find them. As one respondent put it: “I believe Facebook is a good way to find out the news without actually looking for it.”

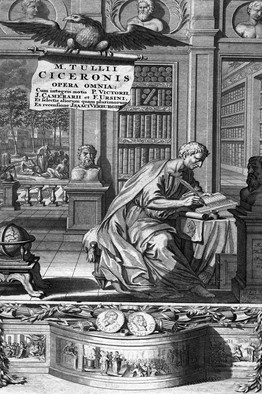

© Bettmann/CORBIS

Mr. Standage, digital editor of the Economist, recounted how information flowed in ancient times in much the way Facebook, Twitter and blogs now operate. In the first century B.C., wealthy Romans kept up with news from around the empire through letters written on papyrus scrolls. Julius Caesar was known for being able to dictate several letters at once. For shorter messages, Romans used rectangular wax tablets that resembled iPads. Poorer Romans scribbled messages on walls.

The book profiles Roman statesman and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, who relied on person-to-person communication; news editors did not exist until centuries later. He once pleaded to a friend: “Whether you have any news or not, write something.”

On another occasion, Cicero warned: “I shall write you nearly every day, for I prefer to send letters to no purpose rather than for you to have no messenger to give one to, if there should be anything you think I should know.” As with Facebook posts today, Cicero was happy to have his views shared. “You say my letter has been widely published: well, I don’t care,” he wrote to a friend. “Indeed, I myself have allowed several people to take a copy of it.”

Even after the printing press, revolutionaries from Martin Luther to Thomas Paine relied on social media for what Mr. Standage calls “signaling and synchronizing opinion”—communicating about a shared desire for social change. Facebook and other social media played this role in the Arab Spring.

The era of mass media dates from the founding of the New York Sun in the 1830s as the first penny newspaper, supported by advertisers instead of subscribers. “Readers were no longer seen as participants in a conversation taking place within the newspaper’s pages,” Mr. Standage wrote. “Instead, they had become purely consumers of information and, potentially, of the products and services offered by the advertisers.”

Radio and television were also built on mass-media advertising. Mr. Standage called such centralized media the opposite of social media, through which people “create, distribute, share, and rework information and exchange it with each other.”

Yet all is not bleak for newspapers and magazines. Mr. Standage cited “finishability” to make the point that in an era of information overload, demanding readers value trusted sources to help them find the news and context they need, while helping them avoid the news they can miss.

That was also true of Cicero, who wanted help making sense of all his social media. In his book, Mr. Standage described how as governor of a remote province Cicero asked a protégé to keep him informed about the goings on in Rome. When he was sent long scrolls of unfiltered news, Cicero wrote back: “Do you really think that this is what I commissioned you to do, to send me reports of the gladiatorial pairs . . . and such tittle-tattle?”

Chastened, the protégé pledged that he would “rather err in the direction of telling you what you don’t desire to know, than that of passing over anything that is essential.” Cicero replied that what he really wanted was for him to use his news judgment “about what is likely to happen.”

That’s still what we want from our sources of news, whether social, centralized, or whatever comes next.