Can Market Timers Beat the Index? Even those who do beat a buy-and-hold strategy in one market cycle have no greater odds of success in the next cycle

July 20, 2013 Leave a comment

July 19, 2013, 6:25 p.m. ET

Can Market Timers Beat the Index?

Even those who do beat a buy-and-hold strategy in one market cycle have no greater odds of success in the next cycle.

MARK HULBERT

If you think you will know it when this bull market finally comes to an end, you are kidding yourself. The vast majority of professional advisers who try to get in and out of the stock market at the right time end up doing worse than those who simply buy and hold through bull and bear markets alike. Even those few who beat a buy-and-hold strategy during one period rarely beat it in the next one. What makes you so confident you can do better?A surer strategy is to keep a steady allocation through thick and thin. If you are frightened by the prospect of another bear market, then you should reduce your equity holdings now to whatever level you would be comfortable holding through one.

Though that means you will miss out on gains if the market keeps rising, odds are that you will more than make up for it by losing less in the next bear market.

Consider the investment adviser—among the more than 200 tracked by the Hulbert Financial Digest—who did the best job of sidestepping the 2000-02 bear market, during which the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index fell 49%, and getting back into stocks close to the beginning of the subsequent bull market.

He is Bob Brinker, editor of an advisory service called Bob Brinker’s Marketimer. Mr. Brinker told clients to sell most of their equity holdings in January 2000, just four days before the Dow industrials hit their bull-market high. His recommendation to get back into stocks came within less than 4% of the October 2002 bear-market low.

The situations in both early 2000 and early 2003 were “textbook” examples of major market turning points, he says.

Unfortunately, his success didn’t carry over to the next market cycle. Mr. Brinker says he failed to anticipate the 2007-09 bear market because it was historically unique—”a once-in-a-lifetime financial train wreck.”

As a result, he kept his model portfolios 100% invested in equities throughout the bear-market decline, which was even more severe than the one following the popping of the Internet bubble. His portfolios on average shed about half their value.

Mr. Brinker’s failure is typical. Consider the 20 market-timing strategies monitored by the Hulbert Financial Digest with the best records over the market cycle encompassing both the 2000-02 bear market and the subsequent bull market. During the 2007-09 bear market, investors following their market-timing advice lost 26%. That was no better, on average, than any of the other monitored advisers.

In fact, the 20 worst timers from the 2000-07 market cycle actually made money in the subsequent bear market. Their portfolios gained an average of 3.2%, while the average market timer lost 26%.

To be sure, one thing that market timers often do well is reduce risk. On average over the past two market cycles, for example, the 20 best timers saved clients from one-fourth of the volatility they would have experienced had they remained 100% invested in the stock market.

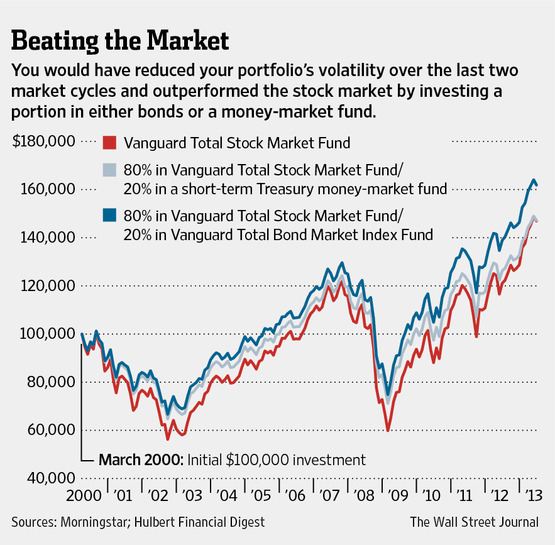

But those clients have paid much for the risk reduction. They could have made more money without more risk simply by constantly adhering to an 80%-20% split between a stock index fund and a bond index fund.

Among the index funds with the lowest fees over the past two market cycles are the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund, which tracks the entire U.S. stock market and has an annual expense ratio of 0.17%, and the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund, which is benchmarked to the investment-grade U.S. bond market and charges 0.2%.

A portfolio that allocated 80% to that stock fund and 20% to that bond fund would have been no more volatile than that of the average market timer over the past two market cycles, yet made a lot more money.

It would have gained an average 3.7% a year from early 2000 through this past June 30, in contrast to 2.1% for the average market timer and 2.9% for a portfolio that was 100% invested in stocks.

You could object that the superior performance of this stock-bond portfolio might not persist, since it benefited from a multidecade bond bull market. But you would have still come out ahead of the average market timer even if you had invested the nonstock portion of the portfolio in a short-term instrument, such as a money-market fund.

Conversely, you could diversify among more asset classes than just stocks and bonds. Consider a portfolio that, over the past two market cycles, was divided equally among U.S. stocks and bonds, international stocks and bonds, gold and a money-market fund.

Such a portfolio would have produced a 5.2% annualized return since the 2000 market top, nearly double the return of the U.S. stock market itself—and this superior return would have been produced with less than half the volatility of U.S. stocks.

An inexpensive way to invest in international stocks is the iShares Core MSCI Total International Stock IXUS -0.02% exchange-traded fund, which has an expense ratio of 0.16%. It tracks all publicly available non-U.S. stocks. To gain exposure to international bonds, you might consider the Vanguard Total International Bond ETF,BNDX -0.36% which charges 0.2%. It tracks all investment-grade non-U.S. bonds.

One of the cheaper ways to invest in gold is the iShares Gold Trust, IAU +0.88% with an expense ratio of 0.25%. Among money-market funds, the most conservative are those that invest in U.S. Treasury bills; one popular choice is the Fidelity Treasury Only Money Market Fund, with an expense ratio of 0.42%.