Pay and economic growth: A shrinking slice; Labour’s share of national income has fallen. The right remedy is to help workers, not punish firms

November 1, 2013 Leave a comment

Pay and economic growth: A shrinking slice; Labour’s share of national income has fallen. The right remedy is to help workers, not punish firms

Nov 2nd 2013 |From the print edition

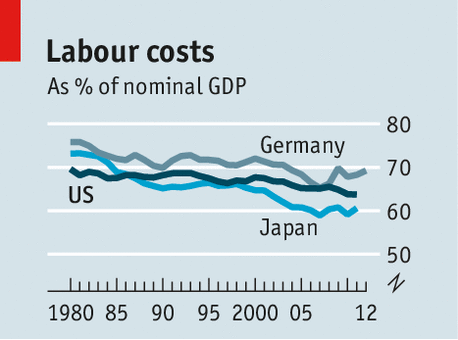

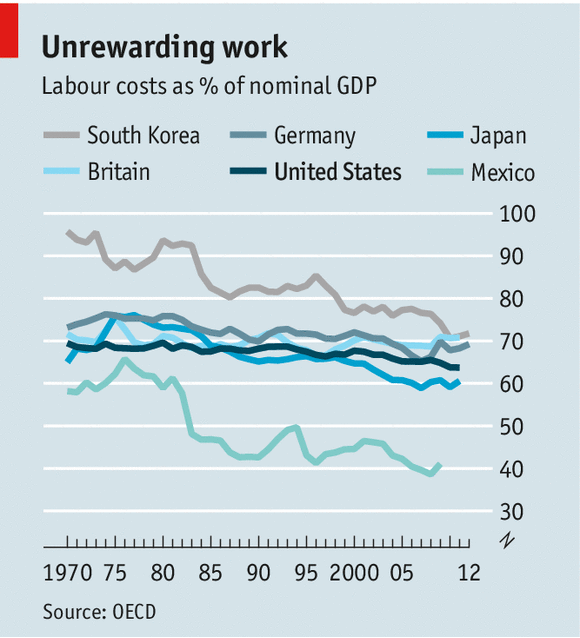

IMAGINE the proceeds of economic output as a pie, crudely divided between the wages earned by workers and the returns accrued to the owners of capital, whether as profits, rents or interest income. Until the early 1980s the relative sizes of those slices were so stable that their constancy became an economic rule of thumb. Much of modern macroeconomics simply assumes the shares remain the same. That stability provides the link between productivity and prosperity. If workers always get the same slice of the economic pie, then an improvement in their average productivity—which boosts growth—should translate into higher average earnings.More recently, however, economics textbooks have been almost the only places where labour’s share of national income remains constant. Over the past 30 years, the workers’ take from the pie has shrunk across the globe (see article). In America, their wages used to make up almost 70% of GDP; now the figure is 64%, according to the OECD. Some of the biggest declines have been egalitarian societies such as Norway (where labour’s share has fallen from 64% in 1980 to 55% now) and Sweden (down from 74% in 1980 to 65% now). A drop has also occurred in many emerging markets, particularly in Asia.

The scale and breadth of this squeeze are striking. And the consequences are ugly. Since capital tends to be owned by richer households, a rising share of national income going to capital worsens inequality. In countries where the gap in wages between high earners and the rest has also increased, the two effects compound each other. In America, the share of national income going to the bottom 99% of workers has fallen from 60% before the 1980s to 50%. When growth is sluggish, as it is now, these shifts mean that most workers are getting a smaller morsel of a smaller slice of a slow-growing pie.

Politically, that is dangerous, and it is producing a lot of predictably polarised debate. The left blames fat-cat firms and the weakness of unions for workers’ declining share. Those on the right, if they acknowledge a problem at all, argue that the fault lies with big government and high taxes.

These explanations are hard to square with the fact that the shrinkage in labour’s share of the pie has occurred in so many countries, with widely differing levels of unionisation and sizes of government. Indeed, studies comparing the trends in different countries’ labour markets suggest that the sorts of things politicians argue about, from corporate-governance rules to trade-union laws, are not what really count here. Bigger global forces seem to be at work. Innovation, especially in information technology, has dramatically increased the wages of workers with the skills to harness it, while hitting others. It has also squeezed labour’s overall share of the pie, as firms substitute ever-cheaper machines for less-skilled workers. Some economists also emphasise the role of globalisation, especially trade with China, in adding to the pinch.

All this points to the sorts of things policymakers can do to help. They should focus on improving the prospects of the low-paid and low-skilled. And they should aim to spread capital’s gains more widely.

The goal should be to strengthen workers without hamstringing firms. Growth, rather than employment protection, is the priority. More work means a stronger labour market, which would bid up employees’ slice, as it did in America in the 1990s when unemployment was at record lows. But even in a growing economy a worker competing with a machine can lose out. So education and training need a reboot too: a greater emphasis on technical subjects, from maths to mechanics, would help ensure that more workers are not replaced by machines but design and operate them.

The charms of popular capitalism

Other sensible reforms may seem counterintuitive. A cut in corporate tax rates is one: combined with a narrowing of the difference between tax rates on individuals’ income from capital and from labour (which is often more heavily taxed), the result would be a more efficient system that promoted economic growth, and thus jobs. Policymakers could also think more creatively about broadening capital ownership, whether through pension reform or more privatisation. Paradoxical as it may sound, a good antidote to labour’s falling share of national income would be to boost ordinary workers’ share of capital.

Workers’ share of national income

Labour pains

All around the world, labour is losing out to capital

Nov 2nd 2013 |From the print edition

ON AN enormous campus in Shenzhen, in the middle of China’s manufacturing heartland, nearly a quarter of a million workers assemble electronic devices destined for Western markets. The installation is just one of many run by Foxconn, which churns out products for Apple among other brands, and employs almost 1.5m people across China. In America Foxconn has become a symbol of the economic threat posed by cheap foreign labour. Yet workers in China and America alike, it turns out, face a shared threat: they have captured ever less of the gains from economic growth in recent decades.

The “labour share” of national income has been falling across much of the world since the 1980s (see chart). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of mostly rich countries, reckons that labour captured just 62% of all income in the 2000s, down from over 66% in the early 1990s. That sort of decline is not supposed to happen. For decades economists treated the shares of income flowing to labour and capital as fixed (apart from short-run wiggles due to business cycles). When Nicholas Kaldor set out six “stylised facts” about economic growth in 1957, the roughly constant share of income flowing to labour made the list. Many in the profession now wonder whether it still belongs there.

A falling labour share implies that productivity gains no longer translate into broad rises in pay. Instead, an ever larger share of the benefits of growth accrues to owners of capital. Even among wage-earners the rich have done vastly better than the rest: the share of income earned by the top 1% of workers has increased since the 1990s even as the overall labour share has fallen. In America the decline from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s is roughly twice as large, at about 4.5 percentage points, if the top 1% are excluded.

Workers in America tend to blame cheap labour in poorer places for this trend. They are broadly right to do so, according to new research by Michael Elsby of the University of Edinburgh, Bart Hobijn of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and Aysegul Sahin of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. They calculated how much different industries in America are exposed to competition from imports, and compared the results with the decline in the labour share in each industry. A greater reliance on imports, they found, is associated with a bigger decline in labour’s take. Of the 3.9 percentage-point fall in the labour share in America over the past 25 years, 3.3 percentage points can be pinned on the likes of Foxconn.

Yet trade cannot account for all labour’s woes in America or elsewhere. Workers in many developing countries, from China to Mexico, have also struggled to seize the benefits of growth over the past two decades. The likeliest culprit is technology, which, the OECD estimates, accounts for roughly 80% of the drop in the labour share among its members. Foxconn, for example, is looking for something different in its new employees: circuitry. The firm says it will add 1m robots to its factories next year.

Cheaper and more powerful equipment, in robotics and computing, has allowed firms to automate an ever larger array of tasks. New research by Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman of the University of Chicago illustrates the point. They reckon that the cost of investment goods, relative to consumption goods, has dropped 25% over the past 35 years. That made it attractive for firms to swap labour for software whenever possible, which has contributed to a decline in the labour share of five percentage points. In places and industries where the cost of investment goods fell by more, the drop in the labour share was correspondingly larger.

Other work reinforces their conclusion. Despite their emphasis on trade, Messrs Elsby and Hobijn and Ms Sahin note that American labour productivity grew faster than worker compensation in the 1980s and 1990s, before the period of the most rapid growth in imports. Studies looking at the increasing inequality among workers tell a similar story. In recent decades jobs requiring middling skills have declined sharply as a share of total employment, while employment in high- and low-skill occupations has increased. Work by David Autor of MIT, David Dorn of the Centre for Monetary and Financial Studies and Gordon Hanson of the University of California, San Diego, shows that computerisation and automation laid waste mid-level jobs in the 1990s. Trade, by contrast, only became an important cause of the growing disparity in wages in the 2000s.

Trade and technology’s toll on wages has in some cases been abetted by changes in employment laws. In the late 1970s European workers enjoyed high labour shares thanks to stiff labour-market regulation. The labour share topped 75% in Spain and 80% in France. When labour- and product-market liberalisation swept Europe in the early 1980s—motivated in part by stubbornly high unemployment—labour shares tumbled. Privatisation has further weakened labour’s hold.

Such trends may tempt governments to adopt new protections for workers as a means to support the labour share. Yet regulation might instead lead to more unemployment, or to an even faster shift to automation. Trade’s impact could become more benign in future as emerging-market wages rise, but that too could simply hasten automation, as at Foxconn.

Accelerating technological change and rising productivity create the potential for rapid improvements in living standards. Yet if the resulting income gains prove elusive to wage and salary workers, that promise may not be realised.