Big Oil’s Tricky Mix of Shale and Scale

November 4, 2013 Leave a comment

Big Oil’s Tricky Mix of Shale and Scale–Heard on the Street

Size Isn’t an Advantage in the Shale Patch

LIAM DENNING

Nov. 3, 2013 3:32 p.m. ET

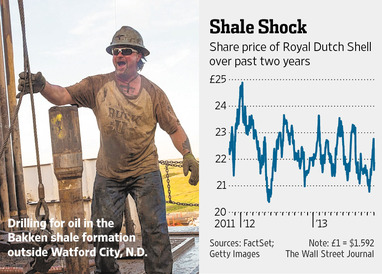

If you are going to be big, you have to make it work for you. The problem for Big Oil is that one of the world’s biggest opportunities, shale, doesn’t necessarily reward bigness. Royal Dutch Shell‘s RDSB.LN +1.39% partial retreat from U.S. shale this year suggests it overreached as it scooped up assets there. Latecomers always risk getting the crumbs after first-movers have picked up the choice cuts. But there also is a structural problem confronting Big Oil.Until recently, majors went anywhere but the onshore U.S., thinking it was tapped out. Instead, they hunted “elephant” fields with huge reserves in deep-water locations or far-flung countries.

This played to their strengths. Huge balance sheets and solid credit ratings allowed them to finance megaprojects. Bob Brackett, analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein, characterizes the majors’ model as deploying capital and technical teams with “lots of command and control.”

One advantage: This model scales easily. A technical team, backed by centralized functions and a common approach, can handle a $1 billion project or a $5 billion one.

Not so with shale. Onshore wells cost a fraction of a deepwater hole in the Gulf of Mexico. So a big balance sheet isn’t a prerequisite to play.

What’s more, shale development requires intensive drilling of many wells rather than the handful common to a conventional project. That makes scale efficiencies harder. Mr. Brackett says a $1 billion, $2 billion or $3 billion shale project “is the difference between a 10-, 20- or 30-rig operation.”

In a presentation last year, consultant PFC Energy, acquired recently by IHS, highlighted the differences. An average well drilled in Angola produces almost 14,000 barrels a day in its first year of production and that output declines by about a fifth in the first four years of operation.

In contrast, a well drilled in the Eagle Ford shale, where Shell is selling assets now, might produce just a few hundred barrels a day in its first year, dropping by more than a third in the first four years.

Another way of considering efficiency is output per employee. This is a crude measure as oil companies use outside contractors. But it illustrates the performance range. Shell, for example, produced just under 46,000 barrels of oil equivalent, or BOE, per employee in its upstream division in 2012. For U.S. exploration-and-production companies, though, performance varies widely, based on data from IHS. At the top end of the range, EOG Resources wrings almost 65,000 BOE from each employee; Chesapeake Energy gets less than 20,000.

In part, this speaks to the variability of shale resources: Early movers do better than latecomers, as Shell has found.

Another factor is the drive for efficiency by competing E&P companies in the shale. Drilling wells faster, experimenting with the number of fractures, or “fracks,” per well, and other operational tweaks are tried at field level, a micro approach that isn’t easy in a big, centralized organization.

That is why Exxon Mobil has left XTO Energy, the shale-gas company it bought in 2010, as a stand-alone division rather than absorb it.

This is sensible approach, if it can be maintained over time. But it also is an expression of just how difficult a time Big Oil has trying not to trip over its own feet when stamping in the shale patch.