The Future of Energy: Predicting what the energy landscape will look like in 20 years

November 12, 2013 Leave a comment

The Future of Energy

Predicting what the energy landscape will look like in 20 years

Updated Nov. 11, 2013 4:19 p.m. ET

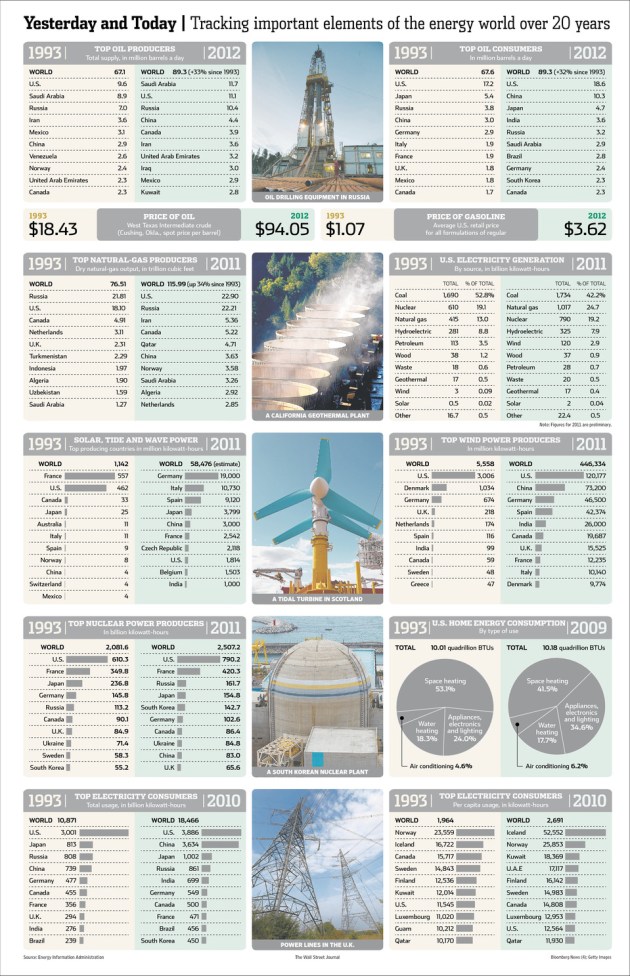

Consider how the energy landscape has changed in the past 20 years. In 1993, the price of oil was a bit over $18 a barrel; it’s around $100 a barrel now. In 1993, the life of a cellphone battery was hardly a concern because there were only 34 million cellphone subscribers world-wide, compared with more than 6.8 billion today. The battery for electric cars mattered even less: It would be another three years before the General Motors EV1 went into production and a year after that before the first Prius went on sale in Japan. Wind farms were a novelty, and solar energy barely registered in the statistics.And how about these numbers: Since 1993, China’s consumption of oil has more than tripled, and its electricity consumption has quintupled.

Now, try to imagine what the energy landscape will look like 20 years from now.

That’s what this Journal Report is all about. It is an attempt to peer into the future, to lay out possible scenarios in a wide range of energy areas. What’s the outlook for advances in energy storage? What has to happen for solar power to truly become a major player in the energy game? Where will hydropower and biofuels fit in? Can deep-water oil exploration overcome its setbacks of recent years? What’s holding back nuclear power—and how can those restraints be overcome? What does the future look like for lighting, for geopolitics, for the energy grid, for energy in developing nations?

In this report, you’ll also find fascinating snippets about energy from The Wall Street Journal’s archives, dating back many decades—snippets that are as exhilarating as they are sobering. Exhilarating because you’ll see how far the world has come in powering the stuff of daily life. Sobering because you’ll also see how many of the most ambitious dreams have yet to be realized, and probably never will be.

There is little doubt that the next 20 years will offer its own exhilarations, its own sobering realities. We can only begin to imagine what those will be.

The Energy Picture, Then and Now

Several key energy indicators from 1993 and today show how much—and how little—things can change in 20 years

Updated Nov. 11, 2013 4:19 p.m. ET

How much might the energy world change in the next 20 years? Let’s look at what has changed over the past two decades.

First, it’s worth seeing how distant 1993 really is. It was the year of the bombing of the World Trade Center, the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the introduction of the first Web browser. Gasoline sold for a little over $1 a gallon, and oil was less than $18.50 a barrel.

Unlike computers and the Internet, energy tends to move relatively slowly. In 1993, for example, the U.S. was by far the world’s biggest consumer of energy, and it still is, though China is moving up fast. When it comes to generating electricity, coal is still king, though its realm is shrinking.

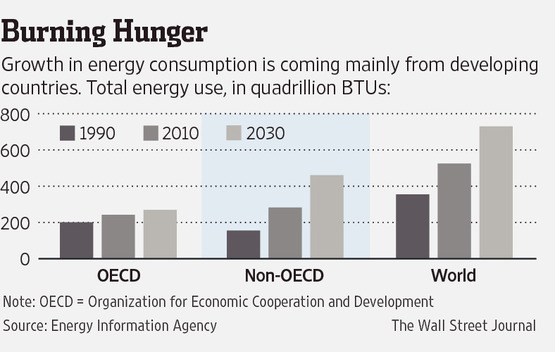

Still, the past two decades have seen some dramatic changes, thanks to new technologies, a steady increase in renewable sources and growing demand in developing countries, especially China. Consider the growth of new oil and natural-gas production methods. It first became economical to extract gas from shale formations in 1998—a breakthrough whose effects few could have foreseen at the start of the 1990s. Now new fields opened by hydraulic fracturing has pushed the U.S. past Russia as the leading producer of natural gas. The boom has caused gas prices to plunge, making the fuel more attractive to utilities and pushing it past nuclear power as a source of energy in electric power plants.

Renewable power sources like wind and solar were minuscule parts of the energy mix in 1993; though still small, their growth has been remarkable. Wind power now generates more electricity than petroleum. Between 1993 and 2011, solar generation has increased more than 2,600%, and Germany, of all places, leads with 19 billion kilowatt-hours of solar generation.

Click on the graphic for several key indicators showing how much—and how little—the energy picture can change in 20 years.

The Future of Energy: The Geopolitics of Oil

Amy Myers Jaffe on why the U.S. of 2033 won’t be vulnerable to cutoffs like the 1973 oil embargo

Updated Nov. 11, 2013 4:19 p.m. ET

“It’s been 40 years since the 1973 oil crisis, when Middle East producers for geopolitical reasons put an embargo on oil to the U.S. If we were to think forward to the 60th anniversary of OPEC—if it still exists—the U.S. by that time will almost certainly be self-sufficient or close to it. Not just because we have our own oil and gas from the unconventional resources. Over that time period we’ll have dramatic changes in the efficiency of our automobiles and our housing and buildings. And because the younger generation is much more inclined to live densely, more inclined to share a car or share a ride, I think the lifestyle in the U.S. will change in a way that makes it look very different from the 1970s.

“It means that no organization or no giant oil-producing country is going to be in the position to blackmail the U.S.

“The country that’s going to be the most vulnerable to an oil-producer cutoff is going to be China. It could be over China’s treatment of its own Muslim population. It could be over China’s arms sales to a particular country or group of countries.

“I would think that the Middle East has the most to lose. That’s because oil and gas prices are definitely cyclical, and even if conflict in the Middle East holds those prices up for some period of time here in the short and medium term, it’s not going to hold it up forever.

“We’re going to move into a world where everyone is going to be an oil producer because we can produce oil from source rock. And we’re still having big conventional finds. So this myth that there would come the day that the whole globe would become dependent on the Middle East, and they could choose any price and they could have all the wealth—those days are ending quickly.

“The other big loser is going to be Brazil. They’re too late to the party. This pre-salt [offshore oil formations found under thick layers of salt] is very difficult, it’s going to be very expensive and the technology is not developed yet. Brazilian oil company Petrobras has not done shale. They didn’t believe in shale. They were betting the entire company store on this pre-salt.

“The same thing with Venezuela—they were so busy being nationalistic that they’ve completely missed the window to do liquefied natural gas, because who’s going to need that gas now in North America?”

The Future of Electric Grids: Distributed Generation

Jay Apt of the Tepper School of Business on why grids are undergoing a transition to distributed power generation and the role natural gas will play

Nov. 11, 2013 4:18 p.m. ET

“The biggest reason I can see for a large-scale transition from current central-station power to distributed generation is if natural-gas prices continue to stay quite low, because of the huge efficiency gains that are possible when you do combined heat and power.

“While we will continue to get some distributed [rooftop] solar power, much of what is going in is central-station solar plants—five megawatts and above—not the rooftop plants.

“So the biggest growth in distributed power may be in natural gas, because of the huge efficiency gains that are possible when you do combined heat and power. A university could say, ‘We could put in a natural-gas power plant for most of our needs, and it would also generate the heat for our buildings in the winter, and for evaporative cooling to cool our buildings in the summer.’

“You could imagine even some large homes getting distributed generation from natural gas.

“If natural-gas prices stay low, it’s quite feasible in the next 20 years that we could see penetration of distributed generation that might equal or surpass the 4% of non-hydroelectric renewable generation. We could imagine getting 8% or 10% distributed generation.

“Whatever natural-gas prices do, you’re going to see more distributed generation for emergency backup. If the folks who believe there will be more climate extremes are proven correct, you’ll see more business cases being made for emergency generators, just as you saw after 9/11.

“Now the question if you’re a CFO is: ‘I’ve got this requirement for emergency generation because the grid’s going to be down the next time Sandy comes by; can’t I use that for distributed generation and get more out of my asset than once every five years?’ “It’s going to be different from what was put in after 9/11. That was mostly diesel generation, and we all know what the cost of diesel fuel is.

“If people put in natural-gas emergency equipment, then we could see that being used as everyday distributed generation.”

— Jay Apt, Professor at the Tepper School of Business and Director of the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center