China Commodity Loans Add to Surge in Offshore Borrowing; Beijing Tries to Limit Flow of Funds; Collateral in Qingdao

June 18, 2014 Leave a comment

China Commodity Loans Add to Surge in Offshore Borrowing

Beijing Tries to Limit Flow of Funds; Collateral in Qingdao

DANIEL INMAN, FIONA LAW and ENDA CURRAN

June 12, 2014 10:35 a.m. ET

The commodity-backed loans at the center of a probe into an alleged financial scam at a Chinese port are part of a ramp-up in offshore borrowing by Chinese companies that Beijing is looking to tamp down.

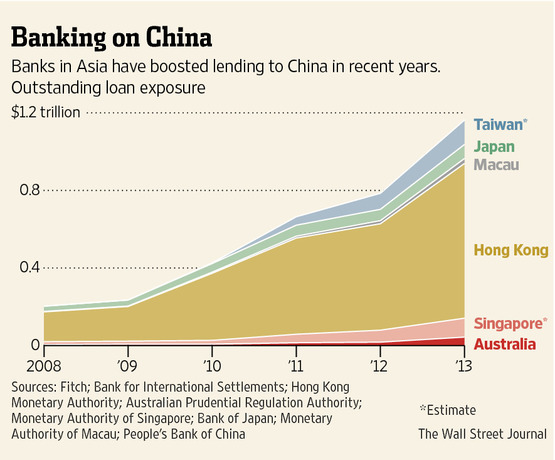

As Chinese authorities tightened credit at home in the past year, local firms instead looked abroad for financing. Asian-Pacific banks alone had $1.2 trillion in loan exposure to China at the end of 2013, up two-and-a-half times from 2010, according to Fitch Ratings.

A chunk of the borrowing has been by Chinese firms taking out short-term overseas loans backed by commodities, part of an effort to lock in gains by borrowing offshore at lower rates, and investing the money at higher rates on the mainland.

This lending has complicated Chinese policy makers’ attempts to slow rapid credit growth in the nation’s so-called shadow banking sector, a network of lenders outside of formal channels. Because many of the loans are denominated in foreign currencies, the use of offshore funds could also increase borrowing costs for Chinese companies if the yuan depreciates further this year.

Commodity-backed loans have come into the spotlight this month as Chinese authorities probe allegations that a trading company in the eastern port city of Qingdao fraudulently took out numerous loans against the same collateral—stocks of copper and aluminum.

Foreign banks have stepped up commodity-backed lending to China in recent years, a profitable business that now is looking increasingly shaky. These banks, including Standard Chartered STAN.LN +0.26% PLC and Citigroup Inc., C -1.11%have made loans worth hundreds of millions of dollars backed by collateral held in Qingdao port, according to people familiar with the matter. A portion of these loans were made to entities linked to Decheng Mining Ltd., a Qingdao trading company, the people said. The lenders are trying to determine whether Decheng Mining used the same collateral for multiple loans.

Both banks have acknowledged potential problems regarding commodity financing in China.

Foreign banks continued to investigate the matter Thursday. China’s government hasn’t commented on the issue. Efforts to reach Decheng Mining weren’t successful.

Concerned by developments—and the possibility of widespread multiple pledging of collateral—foreign banks have begun to withhold new letters of credit used in commodity-backed lending, Western bankers and Chinese metal traders say.

China has become wary about the pace of loan growth. Total credit outstanding in China is more than three times gross domestic product, and the pace of expansion in borrowing is similar to in the U.S. before its financial crisis.

A year ago, Chinese authorities allowed interbank interest rates to rise sharply to damp a rise in onshore bank lending to companies. That has spurred companies to look overseas. Ultralow interest rates offshore are an added incentive: The London interbank offered rate, or Libor, is 0.53% for a one-year loan; the Shanghai equivalent is 5%.

In addition to borrowing directly from banks, Chinese companies draw on the international bond market. Outstanding foreign bonds issued by Chinese companies reached $273 billion at the end of September, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Chinese firms have raised a record $60 billion selling offshore bonds this year, predominately in Hong Kong, according to Dealogic, a data provider.

Commodity-backed loans have become important. Goldman Sachs Group Inc.GS +0.32% estimates that some $110 billion in foreign-exchange inflows in the past four years have come from this kind of lending, or about a third of China’s accumulation of short-term debt in the period.

Some of this money is channelled into loans to local governments and property developers, borrowers that have drawn in increasing amounts of capital, but whose use of debt Chinese authorities are hoping to cool through tighter credit, according to Shuang Ding, an economist with Citigroup in Hong Kong.

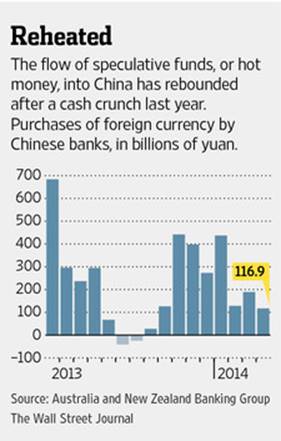

Beijing has taken measures recently to discourage speculators from bringing money into the country; the People’s Bank of China has engineered a 3% drop in the yuan this year. A weaker yuan cuts profits from borrowing abroad to take advantage of higher onshore interest rates.

In mid-2013, authorities limited how much traders could borrow against commodities like iron ore and copper. But that only pushed investors to start using a wider range of collateral, including soybeans and palm oil, according to Goldman.

Citigroup expects Chinese companies to start paying down foreign debt this year, leading to capital outflows. A weaker yuan and rising U.S. yields, which make Chinese interest rates relatively less attractive, could be the catalyst, the bank forecasts.

Capital inflows into China already appear to be moderating. Yuan-currency positions at the nation’s financial institutions accumulated from foreign-exchange purchases—a benchmark for capital flows—fell to 116 billion yuan in April from 437 billion yuan in January.

Others, though, forecast the yuan is unlikely to weaken much further given China’s still-robust economic growth. Foreign lending to China will stay strong given the U.S. Federal Reserve has signaled it won’t raise interest rates until well into 2015 and China still needs credit to fuel growth, they add.

“The current wave of strong offshore financing by Chinese companies will likely continue until the Fed raises interest rates, which will result in higher funding costs,” said Jian Chang, chief China economist at Barclays. BARC.LN -0.31%