The rise of the real collateral ‘mining’ business; The market has under-estimated the degree to which commodity producers, by means of collateral manufacturing, have been propping up commodity prices the past five years

June 10, 2013 Leave a comment

The rise of the real collateral ‘mining’ business

Izabella Kaminska | Jun 05 21:45 | 12 comments | Share

FT Alphaville was cordially invited to talk about the collateralisation of commodities at two separate conferences this past month. We thank IHS Global and the Association des Economiste Quebcois for the opportunity. The crux of our argument was that you can’t really understand what’s going on in commodity markets unless you appreciate that commodities are no longer a pure consumption-based market. More to the point, that marginal prices are increasingly being dictated by the market’s alternative collateral, store-of-value, and safe-asset role in the global economy. This is being fuelled by a general scarcity of quality collateral in the market. For those interested, a copy of our presentation slides can be found here.

To summarise the key points:

The market has under-estimated the degree to which commodity producers, by means of collateral manufacturing, have been propping up commodity prices the past five years. Collateral manufacturing refers to the distinct production of commodities to cater to the demands of the financial sector, rather than to real consumable physical demand. In some way, commodity producers have been playing the role of property developers in what might otherwise be described as the subpriming of commodities. Just like property developers in the naughties, commodity producers have been producing commodities in response to demand that would not be there if not for subsidisation by an investment class keen to overpay for exposure to the asset class.The only differences are that property developers produced homes which could be used usefully even as they served as collateral for a new breed of securitised investment. The second is that when it came to real-estate backed securities, investors sought them out for the higher yields they offered because of the fact that government bonds yields were yielding so little. Investors in this case, were not really taking a punt on house prices themselves. Although the boom they created did lead to other speculative housing market behaviour on the sidelines.

It is our hypothesis therefore that when 2008 happened, and safe yields were obliterated and a scarcity of safe collateral began to plague the market, a great amount of money started seeking out an alternative safe asset.

The commodity diversification story appealed to investors in the circumstances. Unfortunately, it created a situation by which — thanks to the futures market responding to irrational demand from retail focused investment and passive funds — the market began to compensate producers for producing commodities that were not needed by the general consumption market.

The story also made sense to investors because the idea was that commodities (rather than MBS or CDOs with artificially high yields) which would now protect against inflation. It would be commodities that would become the elusive inflation antidote, thanks to a well marketed global scarcity story whose narrative dictated that commodity prices, much like house prices in the naughties, could only one way.

Banks and trading intermediaries were then able to transform these commodities into US Treasury bond (or more like CDO) equivalents by means of hedging in an overpriced futures market, created a high-yielding (contang0-yield) securities, which were gobbled up the smart trading houses and probably the banks themselves. This is because investors were no longer yield hungry, but commodity hungry — that is, they were happy to take completely unhedged positions in commodities because they believed these assets would compensate them in price appreciation terms. Plus, they didn’t have much else to invest in.

The difference with houses is that whilst financially encumbered houses can be used, commodities can’t. The rise in inventories (both light and dark) was the response.

That was the basic argument. There were other, more speculative, elements to the presentation as well — such as the fact that these trends probably originated in 2001 when US rates first fell near zero. But during that time the housing market took a lot of the low-rate slack.

The possible impact on commodities was not so much that they were being demanded as a form of collateral per se but that commodity producers had less of an interest in producing commodities at all. First, because monetising commodities was less attractive in a low interest world — where would you put the money? — and thus could only be justified by extremely high prices. Second, because of the industry’s general attitude towards holding inventories.

It was Keynes who first noted in his Treatise on Money that commodity producers have no interest at all in holding redundant stocks. This is because holding stock costs producers. It costs them deterioration risk, it costs them warehouse and insurance fees, it costs them interest charges and it costs them hedging risk (the risk that the price of commodities may fall before they are sold).

As a result of that, the industry has a tendency to conspire to get rid of redundant stocks — those stocks which are not needed as a buffer to manage supply risk — as quickly as possible. In fact, usually, prices start to collapse as soon as redundant stocks begin to materialise, and the industry thus responds by cutting production to ensure that redundant stocks can be consumed as quickly as possible.

Or as Keynes noted:

Thus the price must fall far enough to curtail production sufficiently to allow the surplus to be absorbed within a period not so long as to eat up, by the costly passage of mere time, too much of the speculative holder’s anticipated gross profit.

But he also noted:

A miscalculation leading to heavy redundant stocks may prove ruinous if matters are allowed to take their course on principles of laissez-faire.

Which he suggested was why cartels had a tendency to appear so frequently in the commodity world.

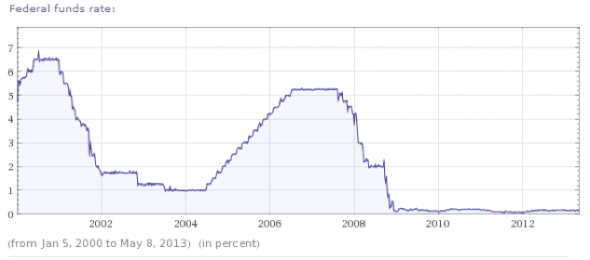

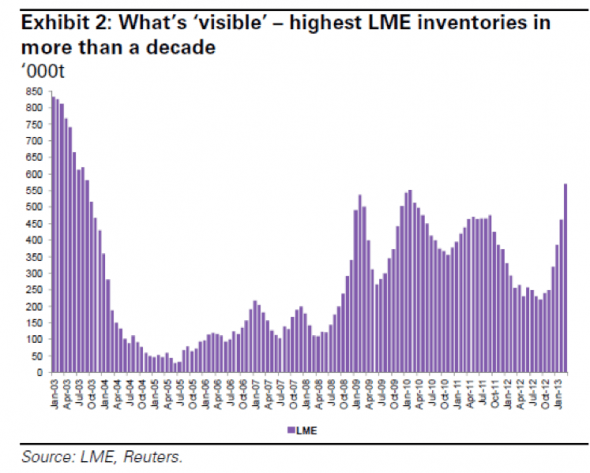

It’s notable not only that the low interest period of the naughties coincided with higher than normal stocks, but that rate-hiking period coincided with a depletion of inventory.

No two charts express this better than the following. First from Goldman, trends in LME inventory levels since 2003:

The second is the Fed Funds Rate in the same period:

The stock depletion coincides almost identically with a rise in interest rates. On that basis it’s possible that the rate hiking period of the naughties incentivised so much inventory monetisation that it ate into very genuine emergency supply buffers — needed to balance the market — making it appear that the market was much tighter from a demand point of view than it really was.

Although what we are really talking about is the marginal barrel, or load: the one that dictates the spot price of the commodity and influences prices. It’s important to remember it doesn’t take much of an imbalance to impact that marginal sum in a world which is still dominated by long-term prices and supply deals.

Working with the notion that the high-interest rates incentivised the conversion of all stock into money as soon as possible, it’s possible the market ran itself into self-made supply crunch, propelling the commodity bull-run of the 2005 onwards period as a result.

The market’s tendency to unwittingly conspire on the matter of stocks, and a misreading of the curve — which ironically, despite the lack of stocks remained in contango in many markets — may also have had the additional effect of disincentivising more production.

At least not until public pressure took its toll in 2007/2008, prices peaked at unsustainable levels for the economy, and — most importantly — rates started to come down, unleashing a veritable flood of commodities back into the market collapsing prices.

So what about now?

It’s hard to say how much of the commodity market has been encumbered in collateral-form due to direct or even indirect passive financial encouragement. This section of the market is very opaque.

What is important is that the behaviour of passive investors is changing. They seem to have finally realised that a) inflation is not such a great concern after all and b) it’s going to be pretty darn hard to break-even on their legacy unhedged commodity investments since the prospect of further price appreciation (which would have to be notable for many of the newcomers to break-even) now looks far less likely.

What’s more, the fact that these investors have started to pull away is already having a notable effect on many commodity markets. Backwardation has returned. But it’s a strange backwardation indeed.

Indeed, while in the 2005 run-up we had a counterintuitive scarcity of stock amid a contango, we now have the opposite: an abundance of stock amid backwardation. Call it scarcity amid plenty.

Again, chances are, the curve signal is being confused for market tightness, despite the contradictory high inventory levels. But really, it may just represent the end of the last high-yielding collateral market. That is, even the commodity market — which until now created good high yielding collateral — has finally fallen privy to yield collapse. Banks and physical intermediaries, meanwhile, can no longer take advantage of attractively priced futures to create to commodity-based positive-yielding assets (by means of contango yield).

Backwardation in this commodity collateral world may thus be a response to private markets pushing the inevitable reality of negative rates upon us. After all, commodities are still in demand as collateral alternatives because collateral scarcity lives on (the high inventory levels, if anything, prove that). Commodity rates have simply finally reattached themselves to money market rates.

If money market rates were better than commodity inventory rates, we’d see the commodity stores disappear quickly. On that basis, any return of a rate hiking cycle will undoubtedly unleash a glut of commodity supply back onto the market as producers and physical players rush to monetise collateral.

Backwardation, of course, still works, it just takes a steeper backwardation to incentivise destocking. But for as long as a collateral scarcity lives on, the market will be willing to encumber and transform ever more commodities into alternative forms of collateral — even at negative rates.

(We guess that’s why Bitcoin is so appealing to so many: it manufactures a whole new form of collateral at a fraction of the production costs of an ordinary commodity (or gold) producer — while simultaneously creating a whole new “this asset can only go up” myth, which encourages the sort of forward price speculation that provides the market with a brand new positive contango-yielding security. Genius.)

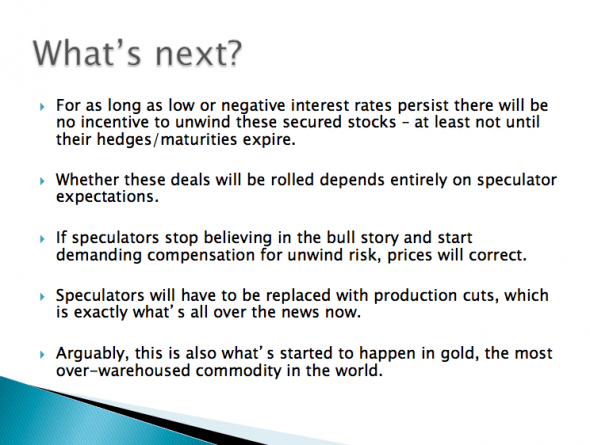

Here, in any case, were our concluding thoughts: