Debt Makes Comeback In Buyouts

June 14, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated June 12, 2013, 6:45 p.m. ET

Debt Makes Comeback In Buyouts

By MATT WIRZ

Shareholders in BMC Software Inc. BMC -0.18% will receive $6.9 billion to sell the corporate-software developer to a group of private-equity firms. But the buyers, led by Bain Capital LLC and Golden Gate Capital, only intend to pay $1.25 billion in cash out of their own pockets. The rest will come from debt raised by BMC to finance its takeover.

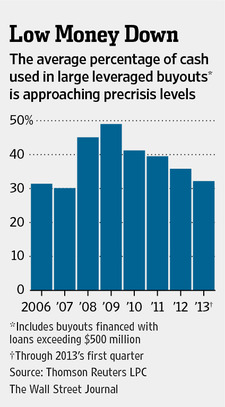

The little-noticed acquisition is another milestone in the return of cheap debt and higher-risk deals to Wall Street: The cash put down by BMC’s private-equity buyers is the lowest as a percentage of the purchase price of any buyout with loans exceeding $500 million since 2008, according to data-provider Thomson Reuters LPC.Debt is the lifeblood of many private-equity deals. The more debt a buyout firm places on the acquired company’s books, and the less cash it contributes, the higher the returns it can fetch on its investment. Ultimately, the debt is paid off with money generated by the company’s operations or the sale of its assets. But more debt can prove risky. Some companies laden with debt by private-equity firms in the mid-2000s struggled during the recession.

The last buyouts with equity contributions comparable to BMC’s were those of Harrah’s Entertainment Inc. CZR -0.88% in 2008 and Clear Channel Communications Inc. in 2007, according to data from Thomson Reuters. Both firms have struggled under the resulting leverage and restructured some of their debts, triggering downgrades by credit raters.

“When these companies do get over-levered, then they struggle to support their debt loads, and that will have an impact on their operations,” said David Breazzano, president of DDJ Capital Management LLC, which manages $6 billion of high-yield bond and loans.

In the BMC deal, Bain Capital LLC, Golden Gate Capital and their co-investors will contribute 18% of the $6.9 billion buyout from their own cash piles, according to an analysis of public filings. Credit Suisse Group AG, CSGN.VX -1.87% BarclaysBARC.LN -1.57% PLC and Royal Bank of Canada RY.T -0.66% have agreed to raise the debt for the deal. Some loan investors say the low percentage is reasonable, because BMC has a strong cash flow to make debt payments.

Even before the financial crisis in 2008, banks rarely raised debt for acquisitions without private-equity firms providing at least a 20% down payment. As recently as last June, so-called “equity contributions” averaged 40%, according to Thomson Reuters data. The average was 32% in the first quarter of 2013.

Some individual and institutional investors like so-called “leveraged loans” that back buyouts because they pay relatively high yields, around 4%, and are “floating” rate, offering some defense should interest rates rise quickly. These investors have plowed at least $150 billion into the market over the past 12 months, according to S&P Capital IQ LCD, making increasingly risky deals possible for private-equity firms.

“The loan-fund managers who are most risk-tolerant are flying high right now,” said Robert Dial, manager of the MainStay Floating Rate fund, which holds assets worth more than $1.3 billion. Funds that use more leverage or buy loans backing riskier buyouts face heftier losses if the credit cycle turns, said Mr. Dial, who doesn’t count his fund in that group. “Not all funds have the same risk profile, and investors should take that into account.”

Still, most of the large buyouts announced this year, including those of BMC, Dell Inc.DELL 0.00% and H.J. Heinz Co., involve companies with strong cash flows and less leverage than boom-era deals like Harrah’s.

“Fitch Ratings does not believe the more aggressive tone over the last year is comparable to the peak of the last credit cycle in 2006-2007,” the credit rater said in a report Monday. The new batch of buyouts involve companies with healthier balance sheets, and financing markets are more stable, the firm said.

Risk in a buyout is most commonly measured as the ratio of debt to earnings before interest taxes, depreciation and amortization, or Ebitda. It is unclear exactly what BMC’s leverage will be post-buyout, but the company’s financial adviser in the sale,Bank of America Corp., BAC -0.46% said its buyer would aim to raise debt equivalent to seven times the company’s Ebitda, according to public filings.

That is below the about-eight-times leverage of some deals at the height of the market a half-dozen years ago, and it is in line with the debt-to-Ebitda of a comparable software-company, Infor Inc., which recently refinanced loans that were used in its buyout.

Software developers like BMC typically produce healthy cash flows, which help make investors comfortable the companies can carry higher debt loads than firms in some other sectors, loan-fund managers say. BMC generated $597 million of free cash flow in the fiscal year that ended March 31, as calculated by J.P. Morgan ChaseJPM -0.58% & Co. analyst John DiFucci.

But some of the figures behind BMC’s buyout point to a riskier-than-average deal. After accounting for the new debt Bain and Golden Gate are borrowing for the purchase, BMC is projected to produce cash flow amounting to 2.3 times its annual interest expense, said a person familiar with the deal. That cash-flow cushion is 11% smaller than the average for large leveraged buyouts in the first quarter of the year, according to S&P Capital IQ.

BMC has recently had mixed results, with strong orders growth in its software for distributed, or networked, computers and sluggish growth in its mainframe computing business, according to research by Joel Fishbein, a senior analyst at Lazard Capital Markets.