Nostalgia Swells for Mandela Era; As Markets Fall, South Africans Lament Nation’s Dimmed Prospects

June 14, 2013 Leave a comment

Updated June 12, 2013, 7:46 p.m. ET

Nostalgia Swells for Mandela Era

As Markets Fall, South Africans Lament Nation’s Dimmed Prospects; Statesman Responds to Treatment

By PATRICK MCGROARTY, DEVON MAYLIE and PETER WONACOTT

JOHANNESBURG—With their former president in the hospital and their nation’s economic promise unfulfilled, South Africans are suffering from a powerful moment of Nelson Mandela nostalgia.

On Wednesday, President Jacob Zuma elicited rare across-the-aisle cheers from parliament when he said the 94-year-old statesman was responding to treatment after five days in a Pretoria hospital for a lung infection. “We are very happy with the progress that he is now making following a difficult few days,” Mr. Zuma said in Cape Town.

Mr. Zuma’s comments lightened what has been a hard week for South Africa. On Tuesday—amid both the latest news of Mr. Mandela’s failing health and declines in emerging-market assets across the globe—South Africa’s rand fell to a four-year low against the dollar. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange posted its steepest one-day drop in 20 months.Investors have been cooling on the country for months amid mounting signs that the ruling African National Congress is no longer up to the urgent tasks of generating jobs, curbing corruption and building a collective sense of purpose that inspires a nation once again.

The latest wave of labor turmoil and investor skepticism is testing Mr. Mandela’s post-apartheid promise that racial equality would fuel economic prosperity for all. It is also creating a collective moment to reminisce about Mr. Mandela, as South African newspapers and television screens run highlights from his long career as an anti-apartheid activist and later as president.

His single term, from 1994 to 1999, followed his election triumph as the country’s first black president and paved the way for Mr. Mandela’s ANC to replace a white minority government. But today, say analysts and ordinary South Africans, the sense of possibility of the Mandela era has yielded to a sense of drift under Mr. Zuma.

“The critical element that’s lacking is leadership,” said Robert I. Rotberg, a visiting Fulbright scholar at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, a think tank in Waterloo, Ontario, who recently spent time in South Africa speaking with officials. “They’re not leading; they’re not innovating; and they’re losing the next generation—one of many tragedies.”

That next generation includes a new black middle class that, despite their own economic gains, has become disillusioned. The target of ire for many is a politically connected elite who appear to be benefiting before all others.

“Nelson Mandela wanted everyone to be equal. He was about employment, eradicating poverty,” said Fuzile Moyake, a 25-year-old from Mr. Mandela’s native Eastern Cape province who wants to build an online fashion magazine in Johannesburg. “But the current government, that’s not what they’re striving for. They’re striving for me, myself and I.”

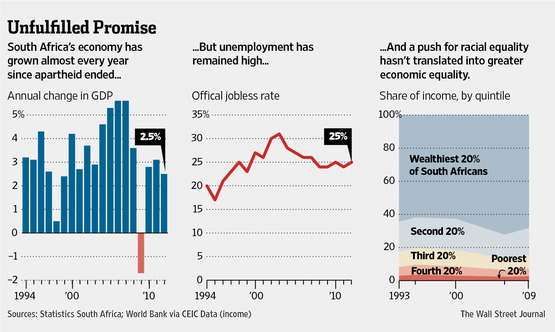

On some scores, the ANC has been an able steward of what was by far Africa’s most developed economy when Mr. Mandela was elected South Africa’s first black president in 1994. The end of apartheid-era sanctions that had strangled the economy in the 1980s ushered in a record 15 years of growth before the global financial crisis in 2009.

Literacy rates and livings standards have improved. More than 15 million people receive welfare grants that have lifted them out of abject poverty. Most of the country’s poor majority now has access to electricity, clean water and affordable housing.

Yet the gulf between rich and poor has widened, making South Africa one of the most unequal countries in the world. The official unemployment rate is 25.2%. Among young people, it is closer to 80%.

Poor and working-class frustrations fueled violent crime that swelled at the turn of the century. More recently, violent worker protests, part of a wave of illegal strikes, have upended production at the mines and factories that underpin the economy.

In August, police shot and killed 34 miners protesting at Lonmin LMI.LN -3.17% PLC’s platinum mine outside Johannesburg, the worst instance of state violence since apartheid. Wage talks scheduled for the next few months at gold, coal and platinum miners—as well as global auto makers—threaten to spark a new round of strikes.

Speaking to parliament on Wednesday, Mr. Zuma said South Africans are far better off than they were before Mr. Mandela came to power, even as he acknowledged some of the mounting challenges. He said police would be deployed to keep strikes peaceful this year, while his deputy president, Kgalema Motlanthe, continues to work with unions and companies to make deals to pre-empt work stoppages.

“There is still a lot of work to be done to achieve a truly nonracial, non-sexist, democratic and prosperous South Africa,” Mr. Zuma said.

The unrest has dimmed South Africa’s prospects among investors.

In February, a closely watched survey of mining executives compiled by the Fraser Institute, a Canadian think tank, ranked South Africa’s policy environment 64 out of 96 countries. That measure of governance was worse than the year before, when it ranked 54 out of 93 countries.

If workers win the double-digit raises that many labor groups have requested, South Africa’s already elevated inflation rate could spike and companies might trim their payrolls, say economists.

Meanwhile, falling commodity prices are already pushing mining companies to try to shrink their workforces, threatening fresh standoffs between employers and employees. Anglo American Platinum Ltd., AMS.JO -2.47% the world’s biggest miner of the rare metal, wants to cut production and dismiss 6,000 employees. Several smaller mining houses are also looking to close unprofitable mines.

Last week South Africa’s top central banker made an unusual plea for officials to broker a deal between workers, unions and employers—one that seemed to be leveled at Mr. Zuma.

“We are facing challenges of crisis proportions that require a coordinated and coherent range of policy responses,” Reserve Bank Governor Gill Marcus said. To boost growth and create jobs, she said, South Africa needs the “government to be decisive, act coherently and exhibit strong and focused leadership from the top.”