Missing the Target: Target-date funds have become one of the most important ways that Americans save for retirement. But for many investors, the funds are still wide of the mark

June 22, 2013 Leave a comment

June 14, 2013, 6:05 p.m. ET

Missing the Target

By LIAM PLEVEN and JOE LIGHT

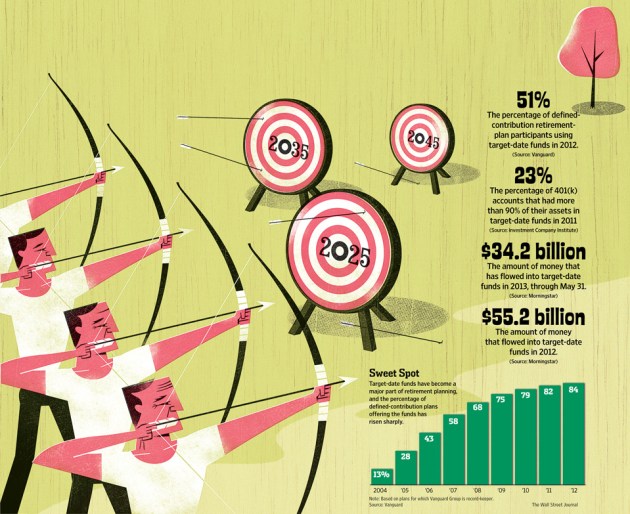

Target-date funds have become one of the most important ways that Americans save for retirement. But for many investors, the funds are still wide of the mark. The funds generally are set up so that investors can put their entire nest egg into a single one linked to the year they expect to retire, in effect putting a savings strategy on autopilot. The funds typically shrink their stock allocation and boost the bond allocation to become more conservative as the retirement date nears.After a 2006 federal law paved the way for many employers to put 401(k) contributions into target-date funds unless workers choose an alternative, the funds added assets rapidly. They held more than $550 billion at the end of May, according to investment researcher Morningstar, MORN +0.32% up from $160 billion at the end of 2008. Fund giants Fidelity Investments, Vanguard Group and T. Rowe Price GroupTROW +1.50% dominate the field, while Wells Fargo, WFC +0.57% BlackRockBLK +0.18% and others also offer funds.

The approach can be particularly useful for people who don’t pay advisers to help them manage their investments.

In practice, though, the simple concept can get complicated, and many investors use the funds in ways designers never intended. A quarter of investors who own target-date funds believe the funds provide guaranteed retirement income, according to a 2012 Securities and Exchange Commission survey—which isn’t true in most cases.

Target-date funds, which are often composed of separate underlying funds, also carry widely disparate fees, and higher-cost funds can cut into investor returns. Some of these underlying funds passively track indexes, while others actively try to beat the market—an approach that can push fees up and lead to diverging performance.

The asset allocations the funds have vary, so two funds with the same target date could look markedly different. Fund companies sometimes add to the confusion by tinkering with the investment recipe, which can expose investors to unexpected risks.

Investors who want to buy a target-date fund often can’t dodge the complications. Many investors have access to the funds in a 401(k) or similar retirement-savings plan through an employer, which often only offers one firm’s target-date funds.

Almost 32,000 of the nation’s largest retirement plans offer target-date funds to nearly 39 million workers, says BrightScope, which rates plans.

Many investors hold them in other accounts. Nearly 30% of the money in target-date funds at the end of 2012 was held in individual retirement accounts, brokerage accounts and other vehicles, according to data from the Investment Company Institute and the Employee Benefit Research Institute, nonprofits based in Washington.

Even fans of the funds can find it tricky to use them. Kent Lind, a high-school science teacher in Waco, Texas, says only a portion of the roughly $750,000 in retirement funds he and his wife, a physician, have amassed is in target-date funds.

He thinks the funds might be a good choice for the entire nest egg, but it is spread out over several retirement plans, with current and former employers, and some have higher-cost target-date options he doesn’t like. Instead, Mr. Lind’s wife holds low-fee stock mutual funds through her employer’s plan, and Mr. Lind uses a bond fund offered by the federal government, where he once worked, to balance her stock risk.

Mr. Lind, who is 49 years old, puts his current contributions into Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2030 Fund to reach the balance between stocks and bonds he wants for the overall portfolio. But only a quarter of that overall portfolio is in target-date funds, he says.

“You have to be creative how you put it all together,” he says.

Despite the shortcomings, target-date funds have already logged a major achievement, experts say, by pushing investors out of low-yielding investments and into the markets, and by adjusting the allocations to stocks and bonds—the so-called glide path—in a way that manages risk.

“In general, target-date funds are great for investors and do a better job of diversifying a portfolio across multiple asset classes than most investors can do on their own,” says Jeremy Stempien, a director of investments at Morningstar.

Investors in target-date funds also seem to behave differently. T. Rowe Price found that investors with 100% of their accounts in a target-date fund were about six times less likely to trade in that account during the course of a year.

Kevin Becker, who is 61 and lives in Plymouth, Minn., used to think about tweaking his investments incessantly. A few years ago, the retired software engineer put most of his retirement money into target-date funds, setting those allocation decisions on autopilot.

“I’ve been sleeping very well since,” he says.

Here are some issues investors should consider in deciding whether to invest in a target-date fund, and if so, how to go about doing it.

• Are target-date funds a good fit?

Four years from now, Vanguard estimates, 47% of workers enrolled in 401(k) and other defined-contribution retirement plans it helps administer will have all of their contributions invested in a target-date fund—as will 75% of new participants.

They have become especially popular with younger workers. Fidelity says 32% of the 11.5 million participants who have access to target-date funds in plans where Fidelity serves as record-keeper have their entire accounts in the funds. Among participants in their 20s, that figure climbs to 61%.

“If you’re 20-something, on your first job, they’re perfect,” says Mr. Lind, the teacher.

Young investors often end up in investments that could be inappropriate for their age. For example, they often put retirement money in the kind of stable-value funds that might be better suited for someone who needs to tap it soon, when in fact retirement is decades away, says Craig Israelsen, co-founder of Target Date Analytics, which studies the funds for employers and financial advisers.

“That’s like preparing to stop at a stop sign a mile before you get there. They were braking way too soon,” he says.

Older investors can benefit from being in a target-date fund, too, says Stephen Nelson, a tax accountant in Redmond, Wash. The funds put asset-allocation decisions on autopilot, which can be useful for investors at a stage in life when financial literacy “can tend to ebb a little bit,” he says.

Yet the same thing that makes target-date funds popular—the one-size-fits-all approach—also can be a weakness, because the funds don’t account for an individual’s specific circumstances.

That is particularly important as investors age, because many other factors can affect investment decisions in or near retirement, including the value of other assets, level of debt, financial commitments to children, number of years before retirement and health.

“There are a lot of differences among 60-year-olds,” Mr. Israelsen says.

He says investors should review their finances as retirement approaches and decide if the target-date fund they are invested in still matches their needs and risk tolerance.

One key question: how much an investor has saved. An investor with no debt, $2 million socked away and confident of covering living expenses, might not want to stay in a target-date fund that has a significant chunk in stocks, says Mr. Israelsen. The investor might not need to take that risk.

For someone who has saved much less and still has significant debt, the decisions can be tougher, Mr. Israelsen says.

That investor may need to weigh whether to stay in a target-date fund with a higher stock allocation in hopes of making up for lost ground, but with the risk of losing money in a down market, or seek out one with a low stock allocation in hopes of preserving assets.

Older investors who expect to pass their assets on to heirs without tapping them might avoid a target-date fund that gets more conservative as they age, Mr. Israelsen says.

• Know your investment.

Two funds with the same target date don’t necessarily have the same proportion of stocks and bonds—but barely half of people who own target-date funds realize that fact, says Rolf Wulfsberg, global head of quantitative research at Siegel+Gale, a strategic branding firm, which conducted the SEC survey.

“There is a lot of misunderstanding,” he says.

In fact, similar-sounding funds can have different risk profiles. The T. Rowe Price Retirement 2030 Fund, for example, has 82% of its assets in stocks and 17% in bonds and cash, while the Fidelity Freedom 2030 Fund is 62% stocks and 38% bonds and cash, according to Morningstar.

For instance, a target-date fund with a higher allocation to stocks might be a bad choice for an investor whose income can vary widely or who is at greater risk of getting laid off or fired, says Ryan Klekar, a financial adviser at wealth-management firm Truepoint in Cincinnati, which oversees $1.4 billion.

Similarly, if an employer’s stock is an important component of the retirement plan, then an investor might need a target-date fund with a lower stock allocation, Morningstar’s Mr. Stempien says.

On the flip side, if an investor has a traditional pension in addition to investments in a defined-contribution plan, the pension should be viewed as a bond, and a target-date fund with a higher stock allocation might be appropriate, he says.

“The whole idea of target-date funds is that there’s some sort of smooth glide path,” says Zvi Bodie, a finance professor at Boston University. In reality, “you’re going to have to make corrections along that path.”

• Be aware of other risks.

Target-date fund managers can also change their strategies.

In February, for instance, Vanguard announced that it was adding a fund that seeks to track an index of international bonds to its target-date series, a move it said would “diversify” the funds. It held the overall allocation to fixed-income investments steady.

Fund companies also can change the proportion of stocks and bonds in a given fund, Mr. Stempien says.

Decisions like that may or may not turn out well, but investors need to be aware that they can happen and understand the possible implications.

“It’s important to look at those disclosures that are given to you,” says Sarah Holden, senior director of retirement and investor research for the trade group Investment Company Institute.

Because the funds hold a mix of assets, sometimes spread out over a dozen or more underlying funds, it also can be difficult for an investor to determine if the funds are doing as well as the markets they follow.

“It’s very easy to mask poor performance,” Mr. Stempien says.

Fees, which eat into returns, also vary significantly. For example, the Fidelity Freedom 2030 Fund, which invests its assets in an array of actively-managed funds and index funds, charges 0.74%, or $74 per $10,000 invested. Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 Fund uses only index funds, and charges 0.17%, or $17 per $10,000 invested.

Other funds charge more than 1% of assets in fees. Investors who think a target-date fund costs too much can see if their retirement plan has lower-cost funds holding the same assets and compose a portfolio with the cheaper funds in the same proportions, says Anthony Webb, senior research economist at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Some target-date funds charge more than the fees on the various underlying funds would support, he says.

“There’s really no justification for these investment managers larding them up with fees,” Mr. Webb says.

• Use it or lose it.

Investors who find an appealing target-date fund have to decide how much to invest in it—keeping in mind that the products are generally designed to hold 100% of an investor’s retirement savings.

“If you trust the strategy, you should just contribute,” says Mike Alfred, chief executive of BrightScope.

Many investors do that, but others don’t. T. Rowe Price says that about one in 10 of roughly 1.8 million participants in plans in which it serves as record-keeper have some of the account balance, but less than 25% of it, in target-date funds.

The risk, advisers and academics say, is that mixing target-date funds in with other investments could skew an investor’s assets in ways that could have costly consequences.

“It adds complexity and may create a lot of overlap,” says Mr. Klekar, the financial adviser.

But even investors who find a good target-date fund and use it wisely need to remember that it won’t solve all their retirement-savings problems.

“People do not save enough,” Mr. Stempien says. “It doesn’t address that.”