An unwind in the great Chinese over-invoicing carry-trade?

June 23, 2013 Leave a comment

An unwind in the great Chinese over-invoicing carry-trade?

| Jun 20 16:16 | 8 comments | Share

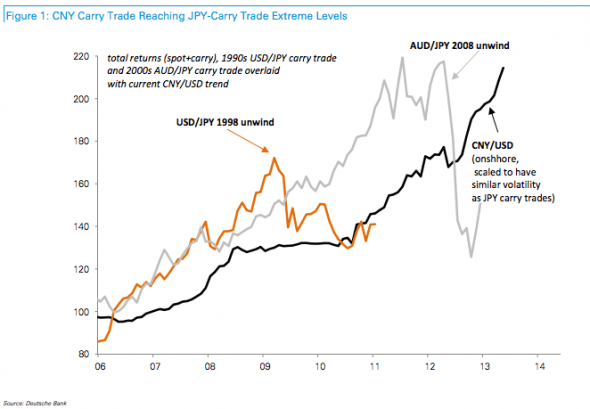

The popular explanation for the rise in Chinese repo rates is being linked to the government’s desire to rein in the shadow banking sector. That is to say the tightness is intentional. But what if it isn’t. What if it has more to do with the unwind of yet another carry trade? Deutsche Bank’s Bilal Hafeez made a strong case for this interpretation last week. We think it’s worth revisiting the argument. There are three main factors that need to be considered, he argued:

Adjusted for volatility China now offers the highest FX carry in the world. This, he says, has led to a surge in flows into the CNY (and CNH) by both onshore and offshore entities over the last few years. The performance of the carry was reaching breaking point last week. Any combination of higher US yields, regulatory clampdown or higher FX volatility or CNY appreciation could trigger an unwind. And as he warned, the demise of the carry trade would then remove an important channel of cheap funding for the Chinese economy.Above all it would also diminish the amount of dollars flowing into the system. Dollars, we should add, that play a vital part in the PBOC’s liquidity distribution mechanism. No dollars, the harder it is to inject CNY liquidity into the Chinese economy. Or more accurately, liquidity injections have to become more dependent on Chinese bond repo.

It’s worth noting that a similar dollar shortage issues arose about the same time last year as well.

One should also consider that China has always been a direct beneficiary of QE programmes (or victim, if you look at it from an FX point of view) in that a lot of the dollars pumped in via the QE programme end up flowing in that direction regardless of what anyone does. Any expected Fed tapering thus has the potential to reduce these inflows.

This is encouraged by the Chinese carry trade opportunity, which as Hafeez noted, was looking pretty frothy about this time last week:

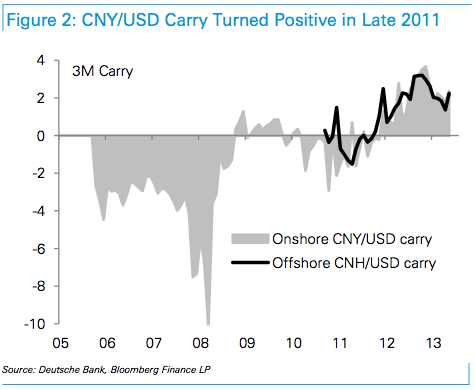

Hafeez estimates the carry turned positive about the end of December 2011:

(This was about the time the dollar shortage issue first became notable, and when flows into CNY became notably less unilateral in nature. Since that time it’s worth noting the Chinese government has also widened the trading CNY/USD trading band, allowing for greater two-way flexibility).

So when things got tight in the Chinese dollar markets last year, the market responded in innovative ways. Remember, the key was attracting fresh cheap dollars into the system, which could be transformed into higher-yielding RMB assets instead.

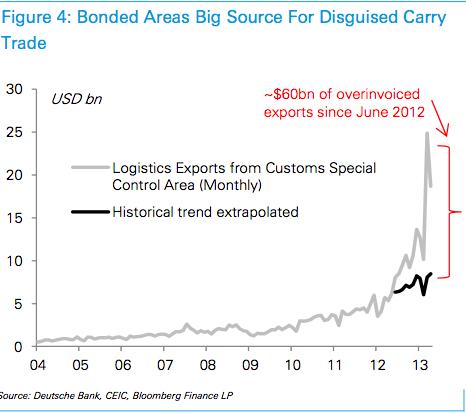

According to Hafeez a big source for the disguised carry trade was the practice of over-invoicing exports in bonded areas:

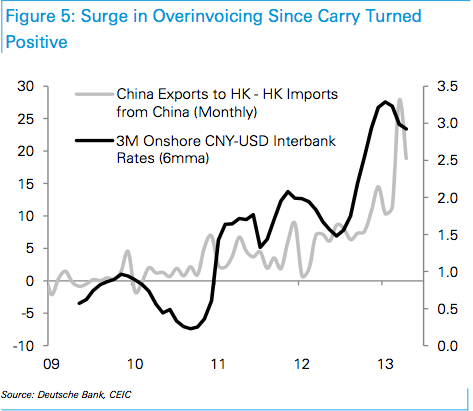

It’s worth noting there has been a veritable surge in invoicing ever since the carry trade became positive:

In short, rather than earning dollars on real exports, China may have turned to borrowing cheap dollars against export collateral instead. First as a means to compensate for lagged export demand and compensatory income, but later because it was incentivised to keep borrowing due to unique opportunity to benefit from one of the best carry-trades in the world — which effectively pays Chinese onshore entities to borrow dollars, exchange into RMB, and sit-back and collect the yield.

At least for as long as FX volatility and US rates remain low.

(Something which compensated for the reduced flow of trade dollars into the system last year. Recent moves to reduce fraudulent transactions, and thus liquidity, are also worth noting here.)

The mechanics of benefitting from the carry-trade however are not that simple, but Hafeez provides a good explainer of how it works here:

Perhaps, the most popular approach of late has been for companies to disguise the CNY/USD carry trade as a trade flow by overinvoicing exports. The full mechanics are described in the appendix, but the essence is for Chinese companies to trade high value- commodities or electronic goods between China and HK, often overstating their value when “exporting” them. Often the goods used never leave the shores of China.They stay in bonded areas where they count as exports, but fail to be recorded as imports in HK (see Figure 3). The scale of this trade can be estimated by looking at the gap between Chinese exports to HK and HK imports from China (see Figure 4). There has been a surge in such activity over the past year, precisely when the carry turned positive. Imports have also been affected by this trade primarily through financing deals that use commodities as a tool to capture the interest rate differential.

The core mechanics:

An onshore corporate obtains USD funding from a bank to import a good held in one of China’s tax-free bonded zones

The corporate exports the good to its offshore subsidiary in Hong Kong. The good does not physically leave the bonded warehouse and is thus not recorded as an import in HK. The exported value can be inflated relative to its imported value if extra funds are to be channeled in. The goods which appear to have been used for this trade include metals like copper and gold as well as electrical machinery. These goods are both more economical to store given high value-to-densities, and their values can be more easily manipulated.

The offshore subsidiary sells the bonded copper back to the supplier and obtains USD. The subsidiary buys RMB at the offshore USD/CNH rate and sends RMB to its onshore parent as payment.

The onshore corporate deposits the RMB in an onshore bank account or a WMP earning a higher CNY yield than it is paying on the USD funding.

The USD funding is rolled, and the trade on the back of the same underlying good can occur multiple times.

Now this sort of thing has been old hat in the copper markets for a long time. The latest incarnation of the carry-trade, however, innovates the process by using goods rather than commodities as the items being collateralised to raise cheap dollar funding.

As Hafeez notes if you’re on an offshore investor with access to dollars, you can easily exploit the carry trade at the same time:

Offshore investors can exploit the carry trade simply by selling USD/CNH, but could face more volatility as the rate is not directly anchored to the daily CNY fix (the onshore FX rate can fluctuate +/-1% around the fix). However, through Chinese entities arbitraging the USD/CNH and onshore USD/CNY markets the two rates are often tied together, thereby unifying the USD/CNH and USD/CNY rates, at least in calmer times.

The onshore CNY deposit rate can also be improved on, by Chinese entities investing in wealth management products (WMPs), rather than deposits (see Figure 5 and 6), thereby earning a yield pick-up. The growth of WMP has coincided with the growth in over invoicing. WMPs are often in turn invested in real estate or the riskier local government investment projects. Companies based in Shenzhen appear to be most active in these activities, so it would come as no surprise that some had spilled over to the Shenzhen stock market, which has outperformed this year.

Hafeez adds the Fed’s relentless QE measures will only have helped secure the carry trade by ensuring that dollar rates were kept low.

Here follow some more fascinating charts:

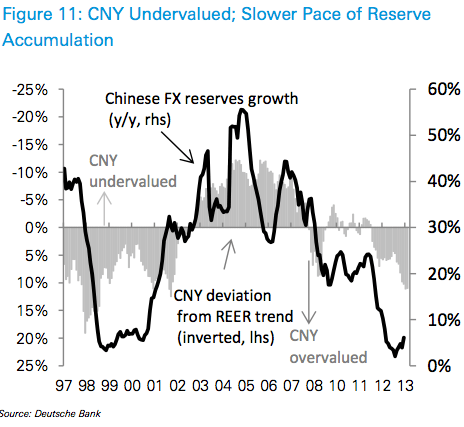

This last one being the most telling of all, since it shows the extent to which the CNY may now have become overvalued rather than undervalued on account of all these shenanigans:

As Hafeez concludes:

The bottom line is that a new carry trade is in play. Most believe it is low risk thanks to ability of China to manage its cross-border flows and its currency. But history suggests caution is warranted. USD/CNH is perhaps most vulnerable to a rally, but more ominously the demise of the carry trade could end an important source of cheap credit for China.

And that is the case, the current repo tightness may have a lot more to do with the carry-unwind, FX volatility and higher US yields.