Which Chinese Banks Have The Biggest Default Risk? Echoes of Mao in China cash crunch

June 23, 2013 2 Comments

Which Chinese Banks Have The Biggest Default Risk?

Tyler Durden on 06/20/2013 20:43 -0400

With China’s credit-to-GDP ratio over 200%, it appears, as Barclays notes, that the PBoC is acting in line with the government’s efforts to deleverage, rebalance and position the economy towards a path for sustainable growth. Though they expect that the PBoC is likely to stabilize the interbank market in the near term (perhaps by more of the same ‘isolated’ cash injections), short-term rates are likely to remain elevated, at least for a while, possibly leading to the failing of some smaller financial institutions. With the small- and medium-sized banks having grown considerably quicker than the larger banks, having been more aggressive on interbank business (i.e. alternative channels to get around lending constraints), thefollowing banks are at most risk of major disturbance of the funding markets remain stressed leaving the potential for retail bank runs or greater fragmentation in the commercial bank market.Via Barclays:

A tipping point

The current liquidity squeeze has roots in a gradual tightening of liquidity in the banking system earlier in the year, but the tipping point was the abrupt drop in FX inflows in May (and likely in June) precipitated by the global unwind of the carry trade and the crackdown on unauthorised FX inflows by Chinese authorities. As the level of excess reserves dropped, banks started to hoard cash, in our view.

Unlike the recent past, the PBoC has not injected funds into the system through reverse repos. On the contrary, by issuing small amounts of bills this week, the bank has signalled its tolerance for the deleveraging process that ensued. Based on our projections, we do not think the liquidity situation will improve in the coming weeks barring strong FX inflows, which we think are very unlikely in the current environment.

The distress in China’s fixed income markets is palpable.

In the absence of prompt policy action, we expect the sell-off in rates to spread to bonds and other fixed income markets. The market will clear over time, but not before a significant level of deleveraging, in our view.

The rout in the fixed income market started at the end of May and accelerated after the three-day Dragon Boat Day holiday (10-12 June), as liquidity conditions did not ease. We think a confluence of several factors has created the tension in the funding market, which has now spilled over into bonds and equities, in our view. The following sequence of events played a role, in our view:

Tight liquidity has been building gradually this year. Banks’ reported excess reserves stood at 2% of deposits at the end of March, according to the PBoC, and we estimate that ratio dropped to 1.4% at the end of May. High deposit growth – a CNY4.2trn jump in March alone – which generated reserve demand of CNY1.47trn during January-May and OMOs that drained CNY478bn of liquidity in that period, were higher than the offsetting FX inflows of CNY1.57trn.

FX inflows dropped sharply in May and are likely to have stayed low or turned negative in June, pushing the excess reserve balance into tight territory. The turnaround was very sudden and driven by global market volatility, in our view. Note that liquidity appeared flush, judging by low repo rates, as late as the second half of May.

The hawkish policy response surprised the market. The PBoC has not responded to surging repo rates by injecting liquidity. Even though it let CNY252bn of repos expire in the first two weeks of June, this was not sufficient to break the trend. Moreover, the PBoC auctioned a token amount (CNY2bn) of 3m bills on 18 and 20 June, signalling tolerance for higher rates. In an unfortunate timing, the squeeze in the funding market came at the time when banks have been in the process of unwinding riskier wealth management products (WMPs) due to regulations introduced in March and require bridge financing for the assets behind those WMPs. Additionally, the rotation out of WMPs into deposits generates demand for reserves, which PBoC is not accommodating.

Facing with the quarter-end liquidity needs, banks are probably hoarding cash now, transmitting the stress into bond, FX and equity markets.

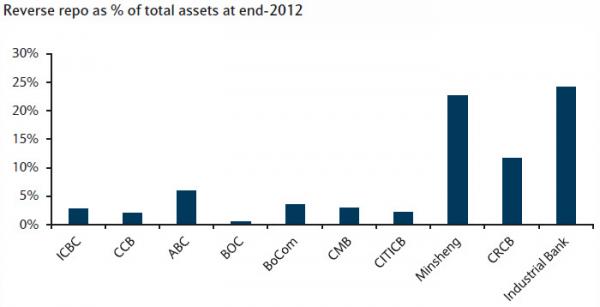

The growth rates of small and medium-sized banks were faster than the large banks (the “big 4” banks). Moreover, they have higher interbank assets as a percentage of total assets than the big banks.

We believe this was mainly because:

1) the small and medium-sized banks were more aggressive on interbank business, which was used as an alternative lending channel to get around the lending quota, and LDR and capital constraints; and

2) they are more dependent on interbank funding to support their business growth.

In particular, we believe some mid-sized banks, such as Minsheng Bank and Industrial Bank, are using credit risk product-based (such as, discounted bills and Trust Beneficiary Rights [TBRs]) reverse repos and repos to arbitrage regulatory requirements. Such assets, which we believe have a much higher default risk than bonds-based reverse repos/repos, grew rapidly at these banks over the past two years.

Minsheng’s reverse repo under discounted bills increased 376% y/y in 2012 and Industrial Bank’s reverse repo under discounted bills and TBR increased 61% y/y in 2012.

In our view, the regulators are more likely to tighten these products in future.

China Money-Market Turmoil Poses Test for New Leaders: Economy

China’s cash squeeze over the past two weeks is testing the management skills of new Communist Party leaders saddled with risks from a record credit expansion under their predecessors.

The one-day repurchase rate touched an unprecedented high of 13.91 percent yesterday, prompting speculation the central bank was forced to pump liquidity, before diving today by the most since 2007. Premier Li Keqiang signaled determination to stamp out speculation funded by cheap money with a June 19 State Council statement saying banks must make better use of existing credit and step up efforts to contain financial risks.

Any prolonged constriction of interbank liquidity risks triggering a broader credit crunch, further depressing an economy that’s already slowing. The dangers add to burdens on a global recovery contending with the prospect of reduced Federal Reserve stimulus in coming months.

“It’s really hard to deflate these things in an orderly way,” said Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University in Beijing. “The problem is that when debt levels have got so high, and it’s more debt that keeps the existing debt afloat, you absolutely have to stop the process but it’s very difficult to stop the process in an orderly way.”

Pettis said the situation is putting pressure on smaller banks because they fund more of their long-term loans from interbank borrowing. The government aims to direct money toward growth rather than speculation after a credit boom that has fueled property-price gains, local-government debt risks, and a wave of wealth-management products.

One-Day Rate

The one-day repurchase rate dropped 384 basis points, or 3.84 percentage points, to 7.90 percent as of 9:33 a.m. in Shanghai, according to a weighted average compiled by the National Interbank Funding Center. The seven-day rate fell 351 basis points to 8.11 percent.

Hao Hong, chief China strategist at Bank of Communications Co. in Hong Kong, said the People’s Bank of China added 50 billion yuan ($8.2 billion) to the financial system yesterday, supplying funds to a single lender, citing unidentified people in the industry. A PBOC press official said he was unaware of the matter, asking not to be named in keeping with bank policies.

The sum was supplied to a single lender through short-term liquidity operations and more banks were in talks to obtain financing, Hong said in a phone interview, adding that this is “proper and appropriate” use of the mechanism.

Shares of Chinese lenders have been under pressure this week. China Minsheng Banking Corp. (600016) has dropped 7.7 percent this week, while Ping An Bank Co. is down 5.8 percent.

Economic Slowdown

Growth has unexpectedly slowed since March, when Li took office as premier, Communist Party chief Xi Jinping became president and the government extended the 10-year tenure of PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan. Besides the hangover from the credit expansion, the economy is hampered by a declining working-age population and rising costs, with analysts surveyed by Bloomberg News this month projecting expansion will decelerate this year and next.

Xi and Li have signaled they’re reluctant to loosen monetary or fiscal policy, instead emphasizing the need for more-sustainable growth in the longer term and policy changes to achieve it.

Bank of China Ltd. said on its microblog yesterday that it made all payments on time yesterday and has never had a capital default. A spokesman for Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. declined to comment on whether the lender received any financing from the central bank.

The yield on top-rated commercial banks’ six-month debt rose 91 basis points yesterday to 5.87 percent, the highest in ChinaBond data going back to 2007.

Policy Shifts

Li’s face-off with banks over money-market rates may help determine whether he can push through policy shifts on interest rates and the capital account, said Yi Xianrong, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. Some changes may be decided at a Communist Party gathering in October.

“It seems the government has decided that it will keep disciplining banks and is ready to sacrifice a few small banks to pave the way for necessary structural reforms,” Yi said. Li’s government is “trying hard to control banking risks and to gradually solve the risks accumulated in the last decade.”

The risk is that higher interbank borrowing costs spread to the broader economy, further undermining confidence. The comments from China’s State Council, or Cabinet, indicate that liquidity will remain tight and that industries facing overcapacity may see corporate defaults in the second half, according to Nomura Holdings Inc.

Public Comment

The government and central bank have made no official comments on the increase in money-market rates and didn’t respond to faxed questions from Bloomberg News. By comparison, the Fed responded to a 2007 jump in interbank rates that presaged the global financial crisis by announcing it would provide liquidity “to facilitate the orderly functioning of financial markets,” though it came under criticism for being slow to contain the burgeoning turmoil.

China’s lack of communication to guide investor expectations may stem in part from “practical difficulties in making the reasons for its decisions explicit,” Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said in a report yesterday.

The government’s broadest measure of credit rose 58 percent to a record $1 trillion in the first quarter, with the increase driven by shadow-banking transactions such as trust loans.

Existing liquidity in the market is “still large” and the monetary authority has no intent to inject large amounts of funding, according to a June 17 opinion piece in Financial News, a daily published by the central bank. Some banks are relying on interbank borrowing to fund irregular practices including hidden loans and forged letters of credit, the article said.

‘Punish’ Banks

The PBOC may be refraining from easing the cash squeeze because it and other regulators want to “punish” some small banks that had used interbank borrowing to finance purchases of higher-yield bonds, Bank of America Corp. said in a report yesterday.

The costs to the economy from allowing a jump in interbank rates for a limited period are “very, very low,” said Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for emerging markets at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA in Hong Kong. She cited a lack of “transmission mechanisms,” such as any link between interbank rates and mortgage rates.

“An interbank rate level of 10 percent is definitely not sustainable, and certainly not in line with the central bank’s true intent,” said Shen Minggao, head of China research at Citigroup Inc. in Hong Kong. “If such a high level continues, it can be very damaging to the economy.”

Elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region, New Zealand’s consumer confidence rose in June. Pakistan’s central bank will probably keep its key rate unchanged at 9.5 percent, economists surveyed by Bloomberg News predicted.

In Europe, data from the French labor office will probably reiterate wages rose 0.7 percent in the first quarter.

–Zhou Xin, Kevin Hamlin. With assistance from Luo Jun in Shanghai and Sharon Chen in Singapore. Editors: Scott Lanman, Paul Panckhurst

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Zhou Xin in Beijing at xzhou68@bloomberg.net; Kevin Hamlin in Beijing at khamlin@bloomberg.net.

June 20, 2013 11:51 am

Echoes of Mao in China cash crunch

By Simon Rabinovitch in Shanghai

China’s credit crunch takes a turn for the worse, the question of why the central bank has permitted market conditions to deteriorate so suddenly and so sharply looms ever larger. Short-term money market rates surged to more than 10 per cent on Thursday, a record high and nearly triple their level just two weeks ago, after the central bank refused to inject extra funds into the strained financial system. Analysts have mostly viewed the squeeze in economic terms, as a warning to lenders that they must rein in dangerously fast credit growth. But in the midst of the extreme market stress, a statement issued late Wednesday by the central bank raised the possibility that politics are also playing an important role.

Bankers had been calling for the central bank to ease the pressure and a few investors had even predicted that it might cut interest rates. Instead, the People’s Bank of China ordered a thorough implementation of the new “mass line education” campaign launched this week by President Xi Jinping – a campaign that in its propaganda-style and potential scope carries echoes of the Mao era.

The Communist party cadres that run the central bank were told to attack the “four winds” of “formalism, bureaucracy, hedonism and extravagance”, as demanded by Mr Xi.

“It is quite possible that the central bank’s policies have some connection to Xi’s campaign,” said Willy Lam, an expert on Chinese politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “It seems to be much more serious than the short anti-corruption campaigns launched by Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin [Mr Xi’s predecessors over the past two decades].”

In monetary policy terms, the central bank could certainly be said to be waging war on hedonism and extravagance. The seven-day bond repurchase rate, a key gauge of liquidity in China, surged 270 basis points to more than 10.8 per cent on Thursday – a punitively high rate that could force cash-hungry banks to call in the riskiest of their loans.

“There are definitely political calculations,” said Ken Peng, an economist with BNP Paribas. “The senior leadership is much more worried about ‘correcting behaviour’ and political considerations than just protecting their 7.5 per cent growth target.”

Unlike the cash crunch that occurred in developed markets when the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, the squeeze in China has been almost entirely self-inflicted, a deliberate move by the central bank.

Market players had hoped the central bank might inject extra cash in the economy at a scheduled auction on Thursday. But it rebuffed the pleas for help, putting more pressure on overstretched lenders.

Concerns about financial risks appear to be the immediate trigger for the central bank’s actions. A surge in credit growth at the start of this year, despite a slowdown in the economy, has alarmed regulators.

The central bank wants to send a message to banks to be more cautious in their risk control and to improve their own liquidity management

– Peng Wensheng, China International Capital Corp

The overall credit-to-gross domestic product ratio in China has jumped from roughly 120 per cent five years ago to closer to 200 per cent today, an indication of rising leverage throughout the economy.

Song Yu, an economist with Goldman Sachs, said the tightening was “aimed at preventing the leverage ratio from reaching an even higher level”.

With money market rates soaring, interbank rates have also shot up over the past two weeks. This has punished lenders that have used their privileged access to the stable, central bank-controlled interbank market to fund purchases of risky, high-yielding bonds.

“The central bank wants to send a message to banks to be more cautious in their risk control and to improve their own liquidity management,” said Peng Wensheng, an economist with China International Capital Corp. “It is saying that you cannot expand credit as you like, and then simply rely on the central bank to back you up.”

But the risk of dangerously fast credit growth in China is not new. The biggest change over the past half year has been political, with the ascension of Mr Xi as the country’s new paramount leader.

Zhou Xiaochuan, central bank governor, is believed to have a good personal relationship with Mr Xi. Both are “princeling” sons of Communist revolutionary leaders. Mr Zhou had been expected to retire this year, having reached the mandatory retirement age, but Mr Xi allowed him a special dispensation to remain in office.

Mr Xi’s campaign against the “four winds” was officially announced on Tuesday. The order that central bank cadres across China should study and implement the campaign was transmitted less than 24 hours later, ahead of virtually all other government units.

PBOC Sacrifices Growth as Bank Curbs Invert Swaps

China’s interest-rate traders are the most pessimistic on economic growth in 21 months, as Fitch Ratings says policy makers are focused on fixing the nation’s banks to avert an industry crisis.

The five-year interest-rate swap, which exchanges fixed payments for the floating seven-day repurchase rate, was 32 basis points below the one-year rate as of 11:26 a.m. in Shanghai, the biggest discount since September 2011, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The shorter contract jumped 22 basis points today to 4.2 percent after the finance ministry’s 10-year bond sale drew the lowest bid-to-cover ratio since August 2012.

“The PBOC is doing the opposite of what the banks were hoping it would do,” said Ju Wang, a senior strategist at HSBC Holdings Plc in Hong Kong. “It is focusing on cleaning up the banks’ balance sheets and the financial system in spite of the liquidity squeeze.”

An inverted swap curve is a further sign of waning confidence about the prospects for the world’s second-largest economy, after Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley and UBS AG cut their 2013 growth forecasts. A report yesterday showed property prices are defying government lending curbs and Fitch said the cash shortage reflects a crackdown on shadow banking that will slow expansion.

“We are going to have banking sector problems,” Charlene Chu, Fitch’s head of China financial institutions, said in a Bloomberg Television interview in Hong Kong yesterday. “Those can manifest either in a crisis or they can manifest in slow growth.”

Money Rate

China’s seven-day repurchase rate, a gauge of interbank funding availability, has averaged 6.2 percent in June, the most since the National Interbank Funding Center began compiling a weighted average in 2006. The one-year swap rate rose the most since August 2011. HSBC expects the swap curve to stay inverted until the end of July.

A slowdown in capital inflows has contributed to the cash shortage. Yuan positions at local financial institutions accumulated from sales of foreign exchange, an indication of capital flows into China, rose 66.86 billion yuan in May, the central bank reported on June 14. That was the smallest gain since November.

Failed Auctions

The cash crunch led to failures of debt auctions by the Ministry of Finance and the Agricultural Development Bank of China this month. The central bank added a net 92 billion yuan to the financial system last week, down from 160 billion yuan in the five days through June 6, Bloomberg data show. The PBOC has refrained from using reverse-repurchase agreements to inject funds since Feb. 7.

That has boosted borrowing costs for Chinese companies, with three-month AAA commercial paper rates increasing 102 basis points this month to 4.92 percent, according to Chinabond data.

Regulators are forcing trust funds and wealth management plans to shift assets into publicly traded securities, taking so-called shadow banking funds away from property developers and local-government finance vehicles. The China Banking Regulatory Commission told banks in March to cap investments of client money in debt that isn’t publicly traded at 35 percent of all funds raised from the sale of wealth management products.

Shadow Banks

Fitch’s Chu said shadow banks had thwarted efforts to cool the economy. The increase in money supply has exceeded the government’s 13 percent target every month this year, rising 15.8 percent in May. Aggregate financing, a measure of credit that includes trust loans, stock and bond sales, totaled 9.1 trillion yuan in the last five months, a 50 percent jump from the first five months of 2012.

The cash crunch is “emblematic of some of the shadow banking issues coming to the fore as well as some of the tight liquidity associated with wealth management product issuance, and the crackdown on some shadow channels,” said Chu.

The cost of insuring sovereign notes in China against non-payment jumped 17 basis points since the end of March to 90.5 yesterday, according to data provider CMA, which is owned by McGraw-Hill Cos. and compiles prices quoted by dealers in the privately negotiated market.

Swelling Credit

The size of China’s shadow banking industry may have started to shrink following the curbs, with official data on June 9 showing trust loans fell to 99.2 billion yuan in May. This accounted for 8.4 percent of aggregate financing, down from 16 percent in December.

Chu earlier estimated China’s total credit, including off-balance-sheet loans, swelled to 198 percent of gross domestic product in 2012 from 125 percent four years earlier, exceeding increases in the ratio before banking crises in Japan and South Korea. In Japan, the measure surged 45 percentage points from 1985 to 1990, and in South Korea, it gained 47 percentage points from 1994 to 1998, Fitch said in July 2011.

Domestic government bond markets are showing relatively few signs of stress. Yields for 10-year government debt rose four basis points this month to 3.48 percent, Chinabond data showed. The yuan has appreciated 0.08 percent in June and declined 0.02 percent today to 6.1298, according to the China Foreign Exchange Trade System.

Slowing Growth

PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan said on April 20 that the nation needs to “sacrifice short-term growth” to make reforms in the economy, while new Premier Li Keqiang told German business leaders on May 27 his country is confronted by “huge challenges” as it seeks 7 percent annual growth this decade, down from more than 10 percent in the previous 10 years.

A weak economy, coupled with easing inflation, will give the central bank room to loosen monetary policy, according to Ming Tan, a Hong Kong-based analyst at Jefferies Group Inc.

China’s trade and inflation data for May trailed estimates. Exports rose 1 percent from a year earlier, down from 14.7 percent in April, while imports dropped 0.3 percent. The median estimates of analysts were for 7.4 percent export growth and 6.6 percent import gains. The consumer price index rose 2.1 percent, down from 2.4 percent in April.

“Recent weak macro data and low CPI figures may prompt the central bank to loosen more,” Tan wrote in a research note on June 17. “We believe the PBOC will most likely inject more liquidity through open-market operations.”

Chinese property prices rose at the fastest pace in more than two years in major cities in May, constraining the ability of policy makers to ease credit. New home prices in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou posted the biggest gains since at least January 2011, and 69 of the 70 cities tracked by the government showed increases, the most since August 2011.

“Rising property prices make it difficult for policymakers to loosen monetary policy in the short term,” said Zhang Zhiwei, Hong Kong-based chief China economist at Nomura Holdings Inc., who previously worked at the International Monetary Fund. “We expect the government to continue focusing on containing financial risks in the next month.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Andrea Wong in Taipei at awong268@bloomberg.net

China’s central bank tightens screw on shadow banking system

China’s central bank has sent a “warning signal” to the country’s overextended lenders, as it rejected a plea to increase money supply, pushing short term borrowing costs to a six-year high.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has joined the government’s efforts to tighten the screw on the country’s shadow banking system, which has fuelled the explosive credit growth that has helped to drive China’s economic rebound, but also raised questions over the ability of borrowers to repay loans. Photo: Quirky China News / Rex Features

3:19PM BST 19 Jun 2013

Overnight borrowing costs in China jumped more than two percentage points to 7.69pc, while the seven-day repo rate climbed 1.4 percentage points to 8.24pc, the highest level since October 2007.

Authorities were forced to extend trading by 30 minutes on Wednesday as lenders scrambled for funding amid the liquidity squeeze.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has joined the government’s efforts to tighten the screw on the country’s shadow banking system, which has fuelled the explosive credit growth that has helped to drive China’s economic rebound, but also raised doubts over the ability of borrowers to repay loans.

“The PBOC is trying to teach the banks a lesson,” said Klaus Baader, chief Asia economist at Societe Generale.

“It’s hard to believe that the PBOC like wants to massively destabilise the banking system. They will eventually relent, but they want to force banks to be more responsible with their liquidity,” he said.

Sun Junwei, an economist at HSBC, said the squeeze was likely to continue until the beginning of July, when maturing PBOC bills and government bonds injected cash into the market.

“This is a warning signal to make sure off-balance sheet lending is curbed. Officials want to make sure banks’ borrowing and lending is well matched and that implies tightening is going to stay for a while,” she said.

China’s liquidity squeeze has already hit some lenders. Earlier this month, Everbright Bank defaulted on a 6bn yuan (£625m) loan.

Meanwhile, HSBC lowered its 2013 growth forecast for China to 7.4pc from 8.2pc, citing the government’s measured approach to creating growth, which would be negative for demand in the short term.

“Top officials seem to be less enthusiastic about launching new stimulus, with their latest policy statements dominated by comments about the need to speed up reforms.” said Qu Hongbin, HSBC’s chief China economist.

“Beijing’s focus on speeding up reforms will, once implemented, revitalise private business,” said Mr Qu. “However, it will take time for the impact of the reforms to filter through, so growth is likely to stay lower in the near term, especially given weak global demand.” HSBC also cut its 2014 growth forecast to 7.4pc from 8.4pc.

Investors back away from emerging markets on China fears: BofA survey

8:55am EDT

By Joel Dimmock

LONDON (Reuters) – Emerging markets are suffering a sharp pullback by investors fearful of a shock from China just as confidence in the world economy, and the euro zone in particular, rises, according to a survey of fund managers. The monthly poll from Bank of America Merrill Lynch, published on Tuesday, showed that allocations to global emerging market equities in June hit their lowest level since December 2008, with a net nine percent of respondents now underweight. A net 48 percent of fund managers reported an overweight position in equities overall, up from 41 percent in May and back above the 47 percent level seen in April. The survey, which polled 248 managers with $708 billion in assets, found that a net 25 percent placed emerging markets as the region they would most like to underweight in the coming 12 months, the lowest ever reading. Last week, emerging markets stocks posted their fifth straight week of losses. The fears over China come after a Reuters poll on Tuesday signaled more optimism among equity analysts, and Michael Hartnett, chief investment strategist at BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research, reckoned the survey response looked overdone. “The lows in emerging market equity and commodity allocations suggest the market has over-positioned itself for a shock from China,” he said. China was considered the greatest tail risk among those polled, followed by a potential failure of stimulus measures in Japan. Allocations to commodities reached a record low with a net 32 percent of those surveyed holding underweight positions. Manish Kabra, equity strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, outlined the implications of what looks like a disconnect. “It’s the sentiment that is running out of anything that is linked to emerging market or the commodity cycle. If China actually surprises on the upside in the coming months there is a big bounce ready to come,” Kabra said. The emerging markets gloom stood in contrast to signs of renewed confidence in prospects for the euro zone, where a net six percent of those polled are now overweight equities. That represents a 14 point swing from the underweight position from May. The numbers are most stark among local players, with a net 45 percent of European respondents expecting the economy to strengthen in the coming year, close to double last month’s result. “First of all, expectations have been very low … Anything that is based on mean reversion… cannot be bad forever, then Europe is the place that is more likely to show upside surprises,” said Kabra.

Updated June 18, 2013, 6:17 a.m. ET

China Wrestles With Banks’ Pleas for Cash

By LINGLING WEI

BEIJING—China’s big banks are pressuring the central bank to free up funds to ease an unusual cash squeeze in the world’s No. 2 economy, according to people familiar with the matter, illustrating a stark choice facing Beijing as it grapples with weaknesses in its financial system: add money to its system to help its lenders, or stay the course to rein in a rapid expansion of credit.

The Chinese interbank funding market has seen rates soar since early this month amid slowing foreign-capital inflows and banks’ needs to fulfill investor obligations, among other factors. The squeeze is pushing up banks’ funding costs and could impede a key source of funds for growth even as the economy slows.

In a further sign of tighter conditions, Agricultural Development Bank of China, a state-controlled policy bank, on Monday reduced by a third the size of its planned 26 billion yuan ($4.2 billion) bond offering. The Ministry of Finance, in a rare failure Friday, was unable to sell all of the debt it offered at an auction.

The tight liquidity situation is leading to some calls from Chinese banks for the People’s Bank of China to inject more cash into the market by lowering the share of deposits banks are required to set aside against financial trouble. The measure is known as the reserve-requirement ratio, or RRR. “Internally, we’re hoping for an RRR cut by the end of Wednesday,” said a senior executive at one of China’s top four state-owned banks.

The central bank didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Some analysts, including Xu Gao atEverbright Securities Co. 601788.SH +1.20% in Beijing, expect the PBOC to take measures to ease the liquidity crunch in the coming weeks. The central bank last cut its reserve-requirement ratio in May 2012.

The concern about a credit crunch comes at a time when Chinese officials also are trying to combat the opposite: a credit binge that dates from the stimulus spending of 2009. The two are linked, analysts say. By trying to rein in the long-term credit surge, the PBOC may have produced a short-term credit crunch. But any big intervention by the PBOC—which, unlike the central banks in the West, isn’t independent of the nation’s political leaders—would risk sending a signal that China’s top leaders would rather sacrifice their goal of keeping a lid on credit growth in favor of pumping up domestic economic growth.

That would run counter to the remarks made by Chinese leaders in recent months. Premier Li Keqiang, for instance, has indicated that Beijing is reluctant to change its monetary- and fiscal-policy stance to counter a slowdown while pledging to press ahead with changes that could make the country’s growth more sustainable.

“Right now, an RRR cut would be very controversial, because that would signal a change in macroeconomic policy,” said Li Wei, an economist with Standard Chartered in Shanghai.

Traders and economists cite a sudden reduction in foreign capital inflows—the result of China’s recent crackdown on speculative money flows and of a slowing economy—as one of the main reasons for the cash squeeze. That is because companies aren’t converting as much foreign currency into China’s currency, the yuan, resulting in less yuan funds flowing into the economy. Adding to the shortage of funds is additional demand for cash so that banks can meet the obligations of repaying investors who hold some high-yielding investment products sold by banks, known as wealth-management products.

On Monday, China’s benchmark seven-day bond-repurchase rate reached 6.85% on a weighted-average basis, near its highest level since China started compiling the rate in 2006. The highest level, at 6.9%, was reached Friday.

So far, China’s central bank has appeared to be more willing to keep what it calls a “prudent” monetary-policy stance than to carry out operations aimed at easing banks’ funding constraints. As part of the prudent monetary stance, the PBOC has been trying to stem a surge in credit that could produce a wave of bad debts and financial failures.

Total social financing, China’s widest measure of credit that includes both bank loans and credit created outside formal banking channels, fell by about one-third to 1.19 trillion yuan in May from April, the second month of substantial decline. But the central bank still has a way to go to curb overall lending: In the first five months of 2013, total social financing was up 52% from 2012.

A commentary published on Monday by China’s Financial Times, a newspaper backed by the PBOC, dismissed the prospect of a liquidity crisis in China’s money market but said some individual banks suffered funding problems because they had relied heavily on borrowing short-term funds in the interbank market and exceeded regulatory limits on lending. The article also said banks should sort out the funding problems on their own and shouldn’t count on the PBOC to step in to provide liquidity.

On Tuesday, the PBOC sold two billion yuan worth of 91-day bills the next day. The bill sale means that the central bank drained two billion yuan of liquidity from the money market, a negligible amount that would hardly sway the market but a signal China’s policy makers aren’t yet ready to loosen the grip on money supply. Last week, the PBOC injected a net 92 billion yuan into the market, a small amount relative to Chinese banks’ funding needs.Only 32 billion yuan in central-bank bills and other notes are due to mature this week, meaning the PBOC would have to inject extra liquidity if it wants to improve the funding situation significantly.

Said Wang Tao, an economist at UBS AG: “Through the events over the past week, we think the PBOC has made it clear that overly rapid credit expansion would not be accommodated, and that the PBOC still focuses more on the quantity of credit and money supply rather than on short-term interest rates.”

“In other words,” Ms. Wang said, “if banks let credit growth go too fast, the PBOC doesn’t mind the spike in interbank rates in order to rein them in.” The recent cash crunch may lead to banks trimming their credit exposure and managing liquidity more prudently, she added, even though “there is a small risk that this could lead to a credit crunch in the short run.”

Is This Why The PBOC Is Not Coming To The Rescue?

Tyler Durden on 06/20/2013 18:06 -0400

We have warned a number of times that China is a ticking time-bomb (and the PBoC finds itself between a housing-bubble rock and reflationary liquidity injection hard place) but the collapse of trust in the interbank funding markets suggests things are coming to a head quickly. The problem the administration has is re-surging house prices and a clear bubble in credit (as BofAML notes that they suspect that May housing numbers might have under-reported the true momentum in the market since local governments are pressured to control local prices) that they would like to control (as opposed to exaggerate with stimulus).

Via BofAML:

MoM price momentum holds the key

Looking at past few rounds of tightening since 2010, it appears to us that the primary consideration of the government is MoM price momentum, not YoY growth in price.

70-city average primary housing price growth MoM and volume growth YoY

70-city average home price growth YoY

This makes sense because potential buyers tend to be enticed to rush into the market if they feel persistent upward price pressure. Table 1 lists the timing and measures of the tightening policies since 2007.

Why we think prices may soon jump again

We suspect that May numbers might have under-reported the true momentum in the market. Local governments are pressured to control local housing prices so some of them have resorted to short-term administrative measures, e.g., Beijing might have suspended the launch of any new projects priced above Rmb40k/sqm (China Securities Journal, June 13). More important, monetary policy remains fairly accommodating, real business returns remain unattractive, while shadow banking products appear increasingly risky. As a result, we believe that it’s a matter of time till liquidity will return to flood the housing market.

The new administration should be tougher on property

The new administration has a five-year horizon.

In our opinion, it has two options with regard to the housing market:

1) to continue to handle it with kid gloves and run the risk of a property bubble bursting just when senior officials fight for positions in the next administration; or

2) to kitchen sink it, live with pain upfront and try to implement structural reforms – hopefully by year four or five, the economy will be on the mend.

Option 2 sounds more plausible to us.

and from Credit Suisse:

This … has heightened systemic risk in the financial system, creating policy uncertainty and has further induced market volatility. By allowing the overnight SHIBOR to spike again, the market has a legitimate reason to ask whether the central bank has the will and ability to calm the interbank market which for us brings back the memory of the US government allowing Lehman Brothers to fail.

We have a few observations to offer:

SHIBOR hikes, or even bank failure in settling within the interbank market, happened before, with the latest events in 2011 and 2012;

There appears to be no bank run at the retail level as depositors seem calm, at least for now;

The liquidity crunch has occurred at the interbank market due to duration mismatch and the lack of policy response, but so far, neither have affected the real economy – large SOEs still remain cash rich while SMEs are struggling with liquidity;

How soon the turbulence can be resolved rests on the will of the central bank;

We believe that the State Council has the authority to stop this brinksmanship and probably has the political will to do so, should the situation go too far, but whether they can make a sound judgment on when is “too far,” only time can tell.

The length matters a lot more than the height of the rate spikes in the interbank market. We believe the elevated SHIBOR has not reached its end. The longer this lasts, the more likely that some banks may face serious liquidity issues and that would further undermine the creditability between banks, creating a chain reaction. It is our view that draining interbank liquidity at the interbank market could cause unintended consequences, at a time at which duration and risk mismatch among the banks are severe, account receivables in the corporate sector are surging, and the inflow of FX reserves is decelerating sharply.

As we noted here, while the PBOC may prefer to be more selective (option 1 above) with their liquidity injections (read bank ‘saves’ like ICBC last night) due to the preference to control the housing bubble, when they finally fold (which we suspect they will) and enter the liquidity market wholesale, the wave of reflation will rapidly follow (and so will the prices of precious metals and commodities).

June 20, 2013

Cash Crunch in China as Rising Interest Rates Crimp Lending

By NEIL GOUGH

HONG KONG — China’s financial system is in the throes of a cash crunch, with interbank lending rates spiking Thursday and bank-to-bank borrowing nearly stalled, even as growth in the economy displays signs of slowing further.

China’s interbank and money market rates have soared over the past two weeks, which has made banks and other financial institutions afraid of lending to one another. Those in need of short-term cash, or liquidity, must pay dearly; failure to do so raises the possibility of defaults.

In a worst-case scenario, absent intervention by policy makers, defaults at lenders with the most exposure and shakiest balance sheets could lead those institutions to fail. The damage could spread to other banks, setting off runs on deposits by ordinary Chinese. In the near term, markets will probably continue to be rattled, especially shares in financial institutions.

“China’s interbank market is basically frozen — much like credit markets froze in the United States right after Lehman failed,” said Patrick Chovanec, managing director and chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management. “Rates are being quoted, but no transactions are taking place.”

The interest rate that Chinese banks must pay to borrow money from one another overnight surged to a record high of 13.44 percent Thursday, according to official daily rates set by the National Interbank Funding Center in Shanghai. That was up from 7.66 percent Wednesday and less than 4 percent last month.

China’s policy makers have an arsenal of options at their disposal to inject more money into the financial system, including conducting open market operations — trading in securities to control interest rates or liquidity — or, more drastically, freeing up some of the trillions of renminbi that banks are required to keep on reserve with the central bank, the People’s Bank of China. In the past, when China’s economy has hit a rough patch, the government usually stepped in, forcing state-run banks to pump liquidity into the market, even though there was a risk it could drive up asset prices and lead to overinvestment.

“China’s central bank, by allowing a spike in interbank rates to persist for longer than usual, is sending a message to the market that liquidity needs to tighten and credit growth slow at the margin,” Andrew Batson and Joyce Poon, analysts at GaveKal Dragonomics, wrote Thursday in a research note. “Indeed, the central bank has been using its open-market operations to drain liquidity from the interbank market since January, setting the stage for just this kind of showdown with banks.”

If the central bank’s inaction toward the deepening liquidity squeeze is a form of financial brinkmanship, some analysts see it as aimed at reining in smaller banks that had been tapping the interbank market as a source of low-cost funding for their investment in higher-yielding bonds, or to finance off-balance-sheet activities, or shadow banking.

“The P.B.O.C. and some other regulators could be taking the opportunity of the tight funding conditions to ‘punish’ some small banks which had previously taken advantage of the stable interbank rates,” Ting Lu, China economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, said Thursday in a research note.

Mr. Lu said that although the surge in interbank lending rates could have its desired effect on reckless lenders, “it will undoubtedly disrupt both the financial markets and the real economy if the liquidity squeeze lasts too long.”

China’s economy has been showing signs of a slowdown in recent months. On Thursday, a preliminary survey of factory purchasing managers in June suggested that output in China had fallen to its lowest level in nine months, as manufacturers cut production at a faster pace in response to slack demand both at home and overseas.

The preliminary purchasing managers’ index, published by HSBC and compiled by Markit, dropped to 48.3 points in the first three weeks of June, its lowest level since September and down from a final figure of 49.2 in May. A reading above 50 indicates growth, and anything below signals contraction.

Stock markets across greater China fell Thursday on news of the liquidity situation and manufacturing survey and were the worst performers in Asia. The Hang Seng Index in Hong Kong dropped 2.9 percent, while the Shanghai composite index fell 2.8 percent.

“Manufacturing sectors are weighed down by deteriorating external demand, moderating domestic demand and rising destocking pressures,” Qu Hongbin, HSBC’s chief economist for China, said in a statement accompanying the survey results. “Beijing prefers to use reforms rather than stimulus to sustain growth,” he added. “While reforms can boost long-term growth prospects, they will have a limited impact in the short term.”

The combination of slower economic expansion and the liquidity crunch in the financial sector offers one of the biggest challenges yet to the newly installed leadership in Beijing.

Prime Minister Li Keqiang, who took office in March, has said he plans overhauls that will promote sustainable growth, as opposed to relying on easy credit from state-controlled banks, which helped the country rebound strongly in the years since the 2008 financial crisis.

“While the economy faces up to many difficulties and challenges, we must promote financial reform in an orderly way to better serve economic restructuring,” China’s State Council, or cabinet, said in a statement Wednesday after a meeting presided over by Mr. Li, according to Xinhua, the state-run news agency.

“The central bank wants to accelerate reform,” said Zhu Haibin, an economist at J.P. Morgan. “They want to give the market a lesson: you need to manage your risk and not rely on the central bank.”

Yu Song, an economist at Goldman Sachs, said in a report Thursday that the government’s decision to tighten liquidity to deal with financial risks could slow growth in the near term. But, he added, “the flip side to this new approach is that the reform measures should reduce systemic risks and possibly raise the level of potential growth.”

Louis Kuijs, an economist at Royal Bank of Scotland and former China economist at the World Bank, said in a research note that Beijing’s response to HSBC’s preliminary survey was unlikely to be drastic. “Policy makers would want to see this weakness confirmed by the official P.M.I. and hard activity data before making bold decisions,” Mr. Kuijs said. “Nonetheless, this kind of data will test the resolve of the government to maintain its current relatively firm macro policy stance.”

The surge in interbank lending rates is a similar test for the People’s Bank of China, which, unlike many other central banks, is not independent and reports to the State Council.

The rise in interbank rates began to take off two weeks ago, before China went on a three-day national holiday to observe an ancient dragon boat festival. Banks typically face higher demand for cash before public holidays, and the initial uptick in rates was not considered abnormal at the time.

But as the situation has worsened, the central bank refrained from injecting new money into the system. Benchmark seven-day repurchase rates, another measure of borrowing costs, briefly soared as high as 25 percent on Thursday, up from 8.5 percent on Wednesday, before closing at 11.2 percent.

Some analysts interpret the central bank’s move to allow the cash crunch as part of a campaign to crack down on shadow banking, which they say can sometimes rely on the interbank market as a source of funding.

According to this theory, the central bank is attempting to rein in the issuance of so-called wealth management products in China. These are short-term debt investment products that are marketed by banks as paying stable returns akin to normal bank deposits, but at higher interest rates. The total amount of such products outstanding in China as of March was about 13 trillion renminbi, or $2.1 trillion, according to estimates by Charlene Chu, a senior director at Fitch Ratings in Beijing.

Banks are able to increase their fee income from the sale of these products, but because they do not appear on banks’ balance sheets, there can be little transparency regarding what loans, bonds or other assets have been packaged together under a given product. Moreover, although the products themselves are typically for a short term of, say, three months, the underlying loans they support are often of longer durations — two years, for example.

“To some extent, this is fundamentally a Ponzi scheme,” Xiao Gang, then the chairman of the Bank of China, wrote in an opinion column in China Daily last October, referring to the mismatch between the maturity of wealth management products and the loans they pay for. “The music may stop when investors lose confidence and reduce their buying or withdraw” from the products, he wrote. Mr. Xiao now serves as the chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

June 19, 2013 7:12 pm

The scary parallels of China and Japan

By James Mackintosh

China’s credit-driven boom is beginning to be exposed

In the 1980s the west watched the Japanese “miracle” with wonder and tried to figure out how to copy its success. Britain still believed in the Japanese model in 1990 when Shirayama Shokusan bid for London’s County Hall, to create a luxury hotel over the river from the Houses of Parliament. The Chinese economic model has supplanted Japan (and the US of the 2000s) as the latest favourite – even as growth slows and problems build. Now China’s Wanda plans its own luxury hotel and apartment complex on the Thames.

The parallels between China now and Japan’s credit-driven boom of the 1980s are scary. Credit rating agency Fitch thinks Chinese credit has expanded far faster relative to economic growth in the past four years than during the heyday of Japanese lending at the end of the 1980s, or in South Korea in the four years leading up to its 1998 crisis.

The broadest measure of lending, total social financing, is up 52 per cent this year, while pure credit is growing at twice the pace of the economy.

Already China is topping the list of worries among fund managers. Investors are rapidly becoming experts on the Chinese money markets, where short-term lending rates have more than doubled this month. Hong Kong-listed shares in Chinese banks have tumbled 11 per cent – although domestic bank shares are doing better thanks to government buying.

Is this the beginning of the credit crunch that exposes years of dire lending decisions?

Probably not. The dangers are genuine. Managing the switch away from credit-fuelled investment-led growth is tricky, to say the least. But the money market squeeze is a deliberate policy of the central bank and can be quickly reversed.

Reckless bank lending makes hefty losses or a Japanese-style slow-growth zombie economy much more likely (barring radical reforms). It need not happen quickly, though: with a controlled capital account, there is no risk of hot money fleeing, as happened in Korea. Like the hotel, a China crisis will take time to build.

China credit crunch: Q&A

Jun 21, 2013 2:07pm by Stefan Wagstyl

Bankers in China breathed a sigh of relief after authorities on Friday eased a tight cash squeeze, with money rates falling after the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, reportedly dribbled funds into the banking system.

But, with the central bank keeping quiet about its intentions, analysts expect the authorities to retain a firm grip on the market. So what is going on?

How severe is the squeeze? It’s unprecedented. On Thursday, short-term money market rates surged to all-time highs, with the seven-day bond repurchase rate, a key gauge of liquidity, jumping 270 basis points to 10.8 per cent a year. On Friday, it fell 227 basis points to 8.5 per cent, but that still leaves it near record levels and three times higher than two weeks ago.

Was it a surprise? You bet. Rates began rising earlier in June just before the Dragon Boat holiday, as is normal before festivals, with the authorities draining cash as bank activity goes quiet. The central bank normally turns the tap back on after the break. But this time, it didn’t.

Is it deliberate? It’s looking that way. The central bank is keeping its own counsel, but local media have said it’s all about controlling credit growth.

What’s the problem? In the past 18 months, the authorities have allowed credit to grow to boost a slowing economy and, some say, to smooth the way for a change in Communist party leadership. But the lending increases seem to have gone further than planned, with a 60 per cent rise in “total social financing” – the widest measure of credit – in the first quarter. Bank credit is growing at 22-23 per cent a year, up from 20 per cent in 2012, fuelled by increases in shadow banking. The authorities are concerned about excess credit, bad loans and a surge in property prices.

So are banks at risk? In a system dominated by state-run lenders, everything depends on the state. With its authoritarian powers and huge foreign exchange reserves, Beijing can shore up the system, which in any case seems to be soundly financed – if the numbers are to be believed. China’s stated loan-to-deposit ratio is 72 per cent, compared to 70 per cent in the US and 111 per cent in the eurozone. So there is negligible risk of systemic failure.

That’s not what I asked. Are individual banks at risk? Nobody knows. It depends on what the authorities want to achieve – and the price they are willing to pay. While a handful of central-government-controlled banks dominate the market, there are scores of lenders run by provincial, city and even village authorities. If Beijing simply wants to slow credit growth by a few percentage points, this month’s scare tactics may prove sufficient. But if it really wants to force banks to come clean about their business, including property lending, own up to bad debts and adopt more transparent practices, then the government might decide to drive a few smaller banks to the wall to hammer home the point. The danger with this approach is that you can’t be sure where it will end. Some big banking crises started with some small banks -as in the US savings and loans scandal.

June 21, 2013 4:57 pm

China credit crunch an unlikely prospect

By Simon Rabinovitch in Shanghai

Until a few days ago, the notion that China might face an imminent financial crisis was a prediction that only the bravest of bears dared make.

But when short-term money market rates soared to as high as 28 per cent on Thursday, forecasts of a crisis no longer seemed so outlandish.

China, a bastion of stability throughout the global credit crunch, suddenly had some of the feel of a financial system on the brink: its interbank lending market had frozen, local media reported that one of the country’s biggest banks had defaulted and rumours spread that the central bank had provided targeted cash injections to another major bank.

Yet the panic subsided on Friday, with borrowing costs falling more than 200 basis points – and without the central bank having to make any public pledge to backstop lenders like the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank did when facing their own downward spirals.

So what exactly just happened in China?

The first and most important point about these financial strains is that they are of the government’s own making. China’s banking system is still controlled by the state and the credit crunch has also to a significant extent been controlled by the state.

Until late last week the central bank had consistently injected just enough cash in the banking system through its regular bond auctions to keep money market and lending rates within its target range.

When rates started drifting upwards, most analysts and investors predicted the central bank would step forward with fresh cash. It did not.

“Its decision not to intervene shows that it is committed to tightening the policy stance,” said Zhang Zhiwei, an economist with Nomura.

China powered through the global financial crisis in large part thanks to an explosion of credit, first through the formal banking system and then through a series of “shadow banks” and off-balance-sheet vehicles.

The result has been a remarkable increase of leverage in China. The overall credit-to-gross domestic product ratio has shot up from about 120 per cent to nearly 200 per cent over the past five years.

“The Chinese authorities have the ability to address the liquidity pressures, but their hands-off response to date reflects, in part, a new strategy to rein in the growth of shadow finance by constraining the liquidity available to fund new credit extension,” Fitch Ratings said.

Put another way, regulators have fired a warning shot at the country’s banks. Previously, banks believed they could rely on their privileged access to the central bank-controlled interbank market to borrow at low, steady rates and then turn around to make risky, high-yielding investments. The government is now trying to close that door to them.

A second lesson to draw from the cash squeeze is that the country’s leaders appear more determined than their predecessors to guide China on to a path of slower, more sustainable growth.

Cracks in the Chinese economic model were already beginning to show. Although credit growth has climbed to about 23 per cent year-on-year, nominal GDP growth has slipped below 10 per cent, pointing to a worrying decline in investment returns.

“One consensus among many government officials and policy advisers is that tough decisions on economic reforms could no longer be delayed and that taking some short-term pain is necessary for healthy long-term growth,” said Huang Yiping, an economist with Barclays. “What the People’s Bank of China is doing now is simply a reflection of that overall policy strategy.”

However, a third conclusion from the ructions of the past week is that Beijing is far from omnipotent in its management of the Chinese economy.

By rapping the country’s biggest banks across the knuckles and ordering them to resume lending to other banks, the central bank appears to have been successful in preventing a more serious disturbance. The weighted average bond repurchase rate, a gauge of liquidity, fell to 9 per cent on Friday from 11.6 per cent a day earlier.

But the simple fact that the central bank had to resort to such an extreme measure to get the attention of the market shows that all of the cajoling, threats, rules and regulations of the past few years – when officials first began to express alarm at the surge in credit – had not amounted to much.

So could China face a financial crisis?

The closed nature of the Chinese financial system makes a crisis highly unlikely, said Liu Yuhui, a finance researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

“The credit of the Chinese government forms the backdrop of the entire Chinese financial system. In this kind of system it is almost impossible that banks could go bankrupt,” he said.

But even if a crisis is improbable, the consequences of the past week might be just as unsettling for the rest of the world, said Arthur Kroeber, managing director of GK Dragonomics. The tightening sends a clear message to banks to lend less, he said.

“This stance raises confidence that Beijing will not let the credit bubble get out of control,” Mr Kroeber said. “But it also raises the odds that both credit and economic growth will slow sharply in the coming six to 12 months.”

He forecast that Chinese growth could slow to just over 6 per cent next year – not bad by global standards but a far cry from the 10 per cent average of the past decade.

Pingback: The Chinese Economy: A short guide to its Past, Present and Future | Place du Luxembourg

Pingback: The Chinese Economy: A short guide to its Past, Present and Future | Makronom