A big PBOC bluff? Alot of the FX purchase were the result of borrowed dollars coming into the Chinese system, rather than pure trade dollars, and that much of the RMB liquidity created against those dollars headed straight into the weapons of mass ponzi market instead of Chinese Treasury bills

June 25, 2013 Leave a comment

The PBOC’s “this is not the liquidity crisis you’re looking for” statement at the weekend may have drawn attention, but it didn’t really manage to reassure equity markets. The Shanghai Composite closed over 5 per cent lower on the day. The issue at hand may be linked to this: That would be the Chinese RMB weakening against the US dollar, in the context of a generally strengthening dollar index:

This is worth bearing in mind in light of the ‘other‘ hypothesis explaining some part of the trouble in China at the moment. This is based on the idea that the mother of all carry-trades may be being pushed to its limits by rising US bond yields, FX volatility and Fed taper speculation (if not the Chinese’ own attempt to stamp out over-invoicing practices).Before getting to the general premise — some aspects of which seem to have been misunderstood by Free Exchange here — it’s worth outlining two potentially under appreciated points about China:

QE always ends up impacting China above all other countries due to legacy dynamics. In this way QE possibly represents more of a financial war with the PBOC (focused on finally appreciating the RMB vs the USD, or seeing the Chinese release its USTs) than explicit money printing in its own right. As Paul Krugman has said, contrary to what bond vigilantes believe, the US would in fact be a prime beneficiary of China releasing its USTs to the market.

To combat this, and to appear continuously in charge, China has been doing a fine PR job on the RMB, saying that it’s the one controlling the RMB appreciation path, it’s the one letting it trade in a larger band, and that it’s the one deciding that more foreign settlement should be allowed. As if these decisions are still theirs to make, rather than the obvious consequences of having to fight the QE valuation war, which has now led to a situation where the RMB may in fact be very much overvalued vs the dollar, rather than undervalued as many people still think it is. (Though this is very much a topic of hot debate.)

The other important thing to remember is that China’s role in world trade has been shifting significantly since 2008, as this chart from Societe Generale from May shows:

As the team noted in that context:

While between 2000-07 China’s exports rose at a faster pace than imports, by an average 2.5% per year; since 2008, imports are rising 4.5% faster pace than exports.

This is important because China has traditionally depended on FX purchases linked to its trade surplus to a) control the exchange rate and b) to distribute domestic liquidity into the system. When FX purchases dry up, so does the amount of RMB liquidity that’s distributed into the system which means the PBOC becomes dependent on alternative liquidity distribution mechanisms like repos, reserve ratio cuts and bill maturity.

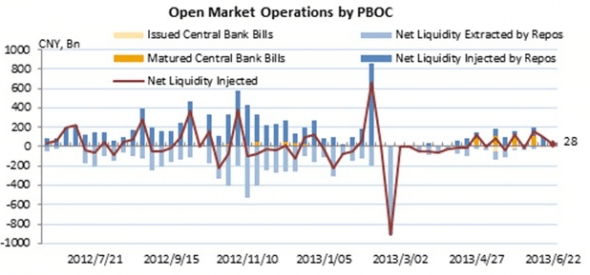

The following chart from ChinaScope shows the degree to which the PBOC has been using repos to conduct its RMB-liquidity ops, and also — importantly — the degree to which central bank bills have been allowed to mature without compensatory issuance.

This is interesting given that China had witnessed six consecutive months of net foreign exchange purchases, suggesting the country was indeed benefiting from capital inflows. As noted here, however, the latest purchases resulted in a net increase of only 66.86 bn yuan, down some 77 per cent from April’s 294.35bn.

The smaller the net yuan injection, the less need for central bank bills to be issued. The greater the liquidity need, the more likely central bank bills are allowed to mature. What’s notable is that since July 2012 there has been very little net positive issuance of central bank bills, despite reserve ratio cuts, and that more recently bills have increasingly been allowed to mature on a net basis.

So how do we reconcile, a) the continuing FX inflows despite the shift in China’s role in world trade and b) the lack of bill issuance to mop up that extra liquidity?

Put another way, where did the FX used to create all that renminbi emanate from and where did the renminbi created by the FX purchase process end up?

One possible explanation is that a lot of the FX purchase were the result of borrowed dollars coming into the Chinese system, rather than pure trade dollars, and that much of the RMB liquidity created against those dollars headed straight into the weapons of mass ponzi market instead of Chinese Treasury bills.

If that’s true, a lot of what appeared to be a net capital inflow may have been an illusion, since the inflow was very much based on carry-trade fundamentals, facilitated by over-invoicing and other collateral-based trade finance shenanigans.

The Chinese government very publicly vowed to crack down on this sort of activity in May, but what’s worth asking is why did it choose to do so at that point? Was it because it genuinely wanted to lead a crack down on the practice, or was it because the government understood that the fundamentals sustaining the practice were likely unwinding in their own right and were soon to bring about nasty consequences that could make it look like the PBoC was losing control.

There’s no better PR management, after all, than making a bad thing look intentional and part of a deeper more considered strategy.

And if that’s true , one can imagine that the PBoC is delighted with everyone interpreting China’s current liquidity problem as being the intentional side-effect of a well-thought out government policy designed to stamp out shadow bank products — rather than the result of a wave of redemptions, brought on by the unwinding of the dollar-financing carry trade.

This also provides a useful explanation as to why the PBoC is not pandering to the sector’s demands for liquidity. And yet the truth may be linked to the fact that the PBoC cannot risk too much RMB liquidity being injected because this would have a detrimental effect on the USD/CNY exchange rate, and put pressure on the dollar shorts which created the surplus RMB in the first place.

And yet, the inability to meet RMB-denominated redemptions would lead to the same end result (dollar defaults) eventually anyway.

If that’s really what’s going on behind the scenes, then the only way to avoid dollar-financing pressure is for the Chinese government to begin liquidating (or repo-ing) some of its USTs so as to alleviate the dollar markets domestically.

In that sense, the Fed taper signal can also be seen as a message to China that it will no longer support cheap dollar financing in China, which is now delaying the inevitable moment that China release its USTs.

Very simplistically, the conclusion is: last year’s dollar shortage problem waspotentially overcome by the opening of a major USD/CNY carry-trade which encouraged dollar borrowing. This was facilitated by the extension of QE. Furthermore, a lot of the net FX purchases of the last year were in fact fuelled by cheap dollar financing, rather than real trade surpluses — themselves synthetically pumped up on paper by fraudulent over-invoicing trends. This itself was encouraged by the out-of-this world returns which were being offered by the Chinese shadow bank market. All of which helped to support the yuan vs the dollar, and delay the inevitable moment that China was forced to liquidate or repo its UST hoards.

Unfortunately, Japan rumbled the whole balance by upsetting the UST demand balance in favour of JGBs — seeing UST yields rise — as well as adding volatility to the FX market, by strengthening the dollar against the yen, which led to Japanese exporters being favoured over Chinese ones.

If this has some bearing on reality — and at this stage most of this is indeed a theory — then one can expect either a spike in Chinese defaults (worsened, if RMB liquidity is dished out by the PBOC) and/or the liquidation of USTs. How likely that is depends entirely on how extensive the dollar-financing carry-trade really was.

If it really was more extensive than people realised, the only thing that can prevent either of the above scenarios playing out is the intensification of the carry-trade itself, or a genuine surge in China’s export business.

Yet, for the carry trade to continue to attract further capital and put off the dollar shortage problem, either the US has to continue to commit to easing, or the PBOC has to tighten enough to ensure that RMB returns domestically continue to more thancompensate for the higher cost of USD funding, and that the RMB remains overvalued relative to the dollar.

It seems likely the Chinese government would prefer a genuine revival of Chinese exports. But it’s unclear how likely that is to happen in a world where China’s role in world trade has begun to shift from being a supplier of low-end manufacturing goods to the much more competitive area of value-added (hi-tech) products.