Markets Brace for Post-Fed World; Air Goes Out of Emerging Stocks

June 29, 2013 Leave a comment

June 28, 2013, 7:43 p.m. ET

Markets Brace for Post-Fed World

Despite Best Yearly Start Since 1999, Investors Spooked by Central Bank’s Signals See Turbulence Ahead

The U.S. stock market had its best start to a year since 1999, but by Friday—the halfway mark of 2013—investors had ditched their party hats and braced for the Federal Reserve to cut back on policies that helped send stocks soaring this year.

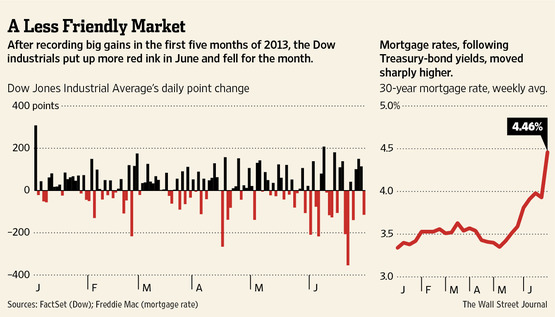

The Dow Jones Industrial Average ended the first six months of the year up 14%, but all the gains came in the first five months. The Dow fell 1.4% in June, including a 114.89 point, or 0.76%, drop on Friday to 14909.60.The impact on financial markets from an anticipated shift in Fed policy in the second half of the year is now a matter of intense debate. In the past week, senior Fed officials have sought to reassure markets the central bank would withdraw its assistance gradually and only if the U.S. economy appeared strong enough.

But some investors said they were bracing for more tumult in the months ahead, as markets face a new, uncertain world.

“We think it is going to be a bumpy summer, a volatile summer,” said Rebecca Patterson, chief investment officer at Bessemer Trust, which manages about $60 billion in New York. Ms. Patterson added that she was optimistic U.S. stocks would pull through with gains.

In June, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke confirmed the central bank’s intentions to start trimming aid this year. But he said any changes would depend on continued economic strength and be limited to gradual reductions in monthly bond-buying. Increases in the Fed’s target short-term interest rates, he said, would require a return to 6.5% unemployment.

The stock market has since swung down and then up as investors tried to predict the fallout. Bond prices took an even bigger hit and yields, which rise as bond prices fall, surged.

Most Fed officials said the markets overreacted to Mr. Bernanke’s news conference, but one said market volatility was a normal reaction to the prospect of a pullback by the Fed.

Investors have become dependent on the Fed’s unprecedented injections of cash into markets, including the current $85 billion-a-month bond-buying program. There is no historic experience to help predict how the unwinding of such an elaborate support system will unfold, creating uncertainty.

Jim Dunigan, chief investment officer at PNC Wealth Management, which oversees about $116 billion, compares a gradual withdrawal to movie hero Indiana Jones trying to grab a diamond from the stones of an ancient tomb without bringing the whole edifice crashing down.

“How do you withdraw the support, which has been massive?” Mr. Dunigan said. “It is hard to do. Throttling back is going to be a little tricky.”

That was revealed this month, when the mere mention of a Fed pullback roiled markets across the globe. Gold ended its worst quarter since the start of modern gold trading in 1974; Brazilian stocks were down 16% and the Australian dollar tumbled more than 12%.

The U.S. bond market, which is the direct recipient of the Fed’s monthly purchases, has been especially hard hit.

Since Mr. Bernanke’s comments, interest rates have jumped higher on credit products from mortgages to Treasury bonds. That has made life harder for such interest-sensitive economic sectors as housing and auto sales.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note rose the most in the second quarter since the fourth quarter of 2010. The yield Friday rose to 2.485% from 1.63% in early May.

Investors took almost $10 billion out of municipal bond funds in the past month, according to data firm Lipper. High-yield bonds tumbled, as did investment-grade corporate bonds.

The bond rout, in particular, startled investors. Fears spread that the bond’s bull market—running for 30 years—might be drawing to a close.

“The transition from a falling-interest-rate environment to a rising interest-rate market is a huge transition,” said Ms. Patterson, of Bessemer Trust. “A lot of people who work on trading floors have never worked in another environment.”

Stocks fell hard in the two days after Mr. Bernanke’s June 19 news conference but recovered somewhat this week. Stock investors were pleased at signs of strength in housing and consumer confidence.

Investors were calmed somewhat by remarks from presidents of some of the Fed’s regional banks, who said they would begin removing support only if the economy is strong enough to handle it. But that message was muddied a bit Friday, when Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker disputed the idea that investors were overreacting.

“The subsequent declines in the bond and stock markets in response are a normal part of the process of incorporating new information into asset prices,” Mr. Lacker said, and are unlikely to interfere with his forecast for moderate economic growth.

Investors have also been troubled by signs of lending strains and slowing growth in China, as that country’s central bank tries to bring runaway lending under control.

The bond market has suffered more than the stock market because in the period since the 2008 financial crisis, bond yields have moved to their lowest levels in many decades. Investors viewed those levels as unsustainable without Fed aid, and they sold bonds heavily once Mr. Bernanke started talking about how soon the aid could start to be withdrawn.

What happened was that bonds shifted back to more normal pricing mechanisms, based more on the level of inflation and less on the expectation of Fed bond-buying, said investment strategist Edgar Peters of asset-management firm First Quadrant LPAMG +1.83% in Pasadena, Calif.

Ordinarily, he said, the yield of the 10-year Treasury note would be around 1.5 to two percentage points higher than the inflation rate. This would suggest a yield of about 3%, he said. Before Mr. Bernanke’s news conference, the yield had been around 2.2%, which was quite low; in fact, it had been well below 2% in May. After the news conference, it moved above 2.5%, as bonds began to return to more normal pricing.

The Fed had hoped the move would be more gradual. But investors had worried for months about a coming rise in bond yields and a drop in bond prices, which would hurt anyone holding bonds. After the news conference, they decided to sell first and ask questions later.

One reason for the resilience of U.S. stocks is that investors have moved money to them as they backed away from bonds and from foreign markets.

June 28, 2013, 7:33 p.m. ET

Air Goes Out of Emerging Stocks

Once-Bullish Investors Pare Back Amid Disappointing Performance

Long a popular destination for investors lured by strong economic growth, emerging markets are losing their attraction.

At the start of the year, investors had expected a friendly backdrop for emerging-markets stocks, thanks to strong economic growth, a pickup in global trade and a flood of easy money from the Federal Reserve and other central banks.

Instead, China is no longer growing at breakneck speed, Turkey and Brazil have been hit by political unrest and expectations are rising that the Fed will pull back its easing efforts in coming months.

In emerging markets, “performance has been below what many, including we, might have expected,” said Michael Gavin, head of asset-allocation research at Barclays BARC.LN -2.72% . “I don’t see any rapid turnaround.”

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has slumped 13% so far in 2013, with most of those losses in May and June. Meanwhile, the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index is up 13% on the year.

Emerging markets haven’t underperformed the U.S. stock market by this wide a margin since 1998, when the effects of the Asian crisis the prior year were still being felt in financial markets.

Investors yanked $22.7 billion out of emerging-market stock funds in the five weeks ended Wednesday, according to data provider EPFR Global. Emerging-market bond-fund managers saw outflows of $5.6 billion in the latest week, a record since at least 2004, when EPFR starting tracking weekly flows.

Recent outflows leave just over $1 trillion in emerging-market stock funds, and come just after the total assets hit a record $1.09 trillion in May.

Some $181 billion has flowed into emerging-market stock funds since the start of 2009, a period that saw outflows of nearly $200 billion from U.S. stocks.

Back in December, a survey of money managers at top investment firms by Russell Investments found more bullishness surrounding emerging-market stocks than any other class of stocks or bonds. Some 165 respondents gauged their performance expectations for 13 assets on scale of one to seven. Two-thirds of managers were optimistic on emerging-market stocks.

Now, some are growing disillusioned and are paring back those wagers.

Greg Peterson, director of investment research at Ballentine Partners LLC, an independent wealth-management firm that oversees about $4 billion in assets, said money managers at his firm debated “whether we bite the bullet and make the call that we got it wrong.” Earlier this month at an investment policy meeting, his firm moved to cut the proportion of emerging-markets it holds in its stock portfolio to 17% from 20%, he said.

“In the short term, we’re thinking that there is a good chance of weakness,” he said.

A lower growth outlook in key markets has prompted T. Rowe Price Group,TROW -0.62% which manages $617 billion, to temper its enthusiasm. The firm has been paring back its emerging-markets stock positions over the past six months, said Charles Shriver, a vice president and portfolio manager, though the firm maintains a long-term bullish view.

“Emerging markets should benefit from the continuing evolution of a developing consumer class,” Mr. Shriver said. “We feel that’s still intact, but recognize that it takes time to develop. It’s not a linear path.”

Brazil’s Bovespa index is down 22% this year, while China’s Shanghai Composite is off 13%. Since peaking last month, the Turkey ISE National 100 Index—among the emerging markets’ brightest stars—has fallen 18% amid unrest in Istanbul.

“For any of us who actually manage money and sit down to face client questions eyeball to eyeball, there’s a certain amount of apprehension about the short-term performance,” said Timothy Leach, chief investment officer at U.S. Bank Wealth Management, which manages around $110 billion in assets.

“We’re continuing to stick to our guns,” he said. “If we liked emerging markets six months ago, we’ve got to like them even more now from a valuation perspective.”

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has a price/earnings ratio of 10.7, its lowest of the year, and well below the S&P 500’s 15.7.

Other investors aren’t as sanguine. Jeff Knight, portfolio manager and head of asset allocation at Columbia Management, a mutual-fund firm that manages about $341 billion, said his firm hasn’t sold its emerging-markets stocks, but is allowing their weight to diminish as prices sink.

“We’re kind of in no man’s land,” Mr. Knight said.